- BY Colin Yeo

Theresa May’s immigration legacy

Theresa May has just announced her resignation. She will leave office on 7 June 2019, leaving a legacy indelibly associated with two things: Brexit and immigration. The gridlock on the former being, infamously, a function of her obsession with the latter, let us look at what May’s many years of trying to reduce immigration to the UK have really achieved.

The hostile environment

Perhaps May’s main legacy is the quiet revolution in immigration policy that is the hostile environment, a toxic system of citizen-on-citizen immigration checks. It was May herself, as Home Secretary, who coined the phrase “hostile environment” in the first place. (The government now prefers the cuddlier term “compliant environment”.)

There was no White Paper on these reforms nor any consultation. The long term impact of asking citizens to conduct “papers, please” immigration checks on one another is unknown.

One of the most obvious immediate direct effects of the hostile environment was the Windrush scandal, though, where legally resident Commonwealth citizens lost their jobs, health care and dignity. The blame for that rests squarely on Theresa May’s shoulders.

There is widespread concern that the hostile environment encourages race discrimination. This seems to be borne out by events. The High Court recently found that one of the key planks of the hostile environment, the “right to rent” policy, caused landlords to discriminate against ethnic minority tenants when they otherwise would not.

Clamping down on refugees

Back in 2015, Home Secretary May said in a big speech that “I want us to work to reduce the asylum claims made in Britain.” She did everything she could to deliver on that but claims actually went up. The year before May delivered that speech, 32,000 asylum seekers and their dependants claimed asylum in the UK. The figure has been higher in every year since: 37,000 people applied for asylum in 2018.

May also claimed in that speech it was immoral not to resettle more refugees. But she failed to expand the number of resettlement places as Home Secretary or as Prime Minister. Instead, May did whatever she could to prevent child refugees in Calais or in the UK being reunited with their family members.

Indeed, May ended the policy of automatic settlement for refugees after five years, deliberately leaving refugees uncertain about whether they would eventually be kicked out of the UK.

And it was Theresa May who introduced the policy that prevents some recognised refugees from getting British citizenship because of the way they entered the UK in the first place.

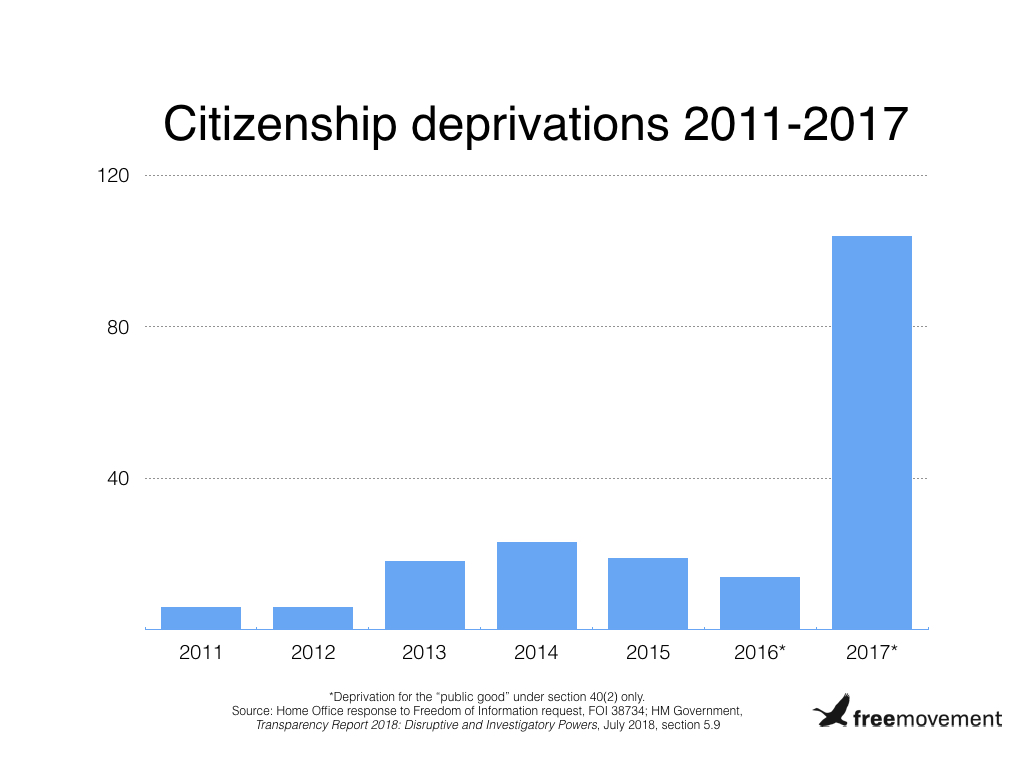

More deprivation of citizenship

Then there was the huge increase in citizenship stripping under Theresa May, much of which was later found to be unlawful by the Supreme Court. This represented a fundamental change in British nationality policy but it happened on the quiet, with the Home Office attempting to withhold the statistics.

Citizenship deprivation is thought to have massively expanded since 2017 under May’s successors. But it was she who broke the taboo on taking citizenship away.

It was also May who introduced a savagely expanded “good character” test for British citizenship applicants, undermining the three/five year residence requirements laid down in Acts of Parliament by introducing a ten-year examination of a person’s immigration history.

Separated families

How about the thousands of “Skype families” created by her harsh new family immigration rules introduced in 2012? Children are being forced abroad or separated from one of their parents by the £18,600 earnings rule.

Let’s not forgot how discriminatory that rule is. Women, ethnic minorities and those outside London are less likely to earn enough to live with their loved ones. That, too, is squarely on Theresa May’s shoulders.

The 2012 family immigration rules also included the effective closure of the immigration route for parents, cruelly forcing British citizens to move abroad to look after their elderly parents. Only those who can prove the parent is so ill that they need daily personal care that can’t be paid for abroad can now sponsor an elderly foreign parent. The case of the Edinburgh-based great-grandparents who the Home Office tried to force out of the country is a recent example of the devastation this policy has caused to families.

May also took away rights of appeal for family visitors coming to the UK, preventing many from attending weddings, funerals, graduations and celebrations.

She abolished immediate settlement for spouses who have lived together outside the UK for four years or more. Now, even those married for decades abroad must pay for visas and wait five years before they can apply for settlement.

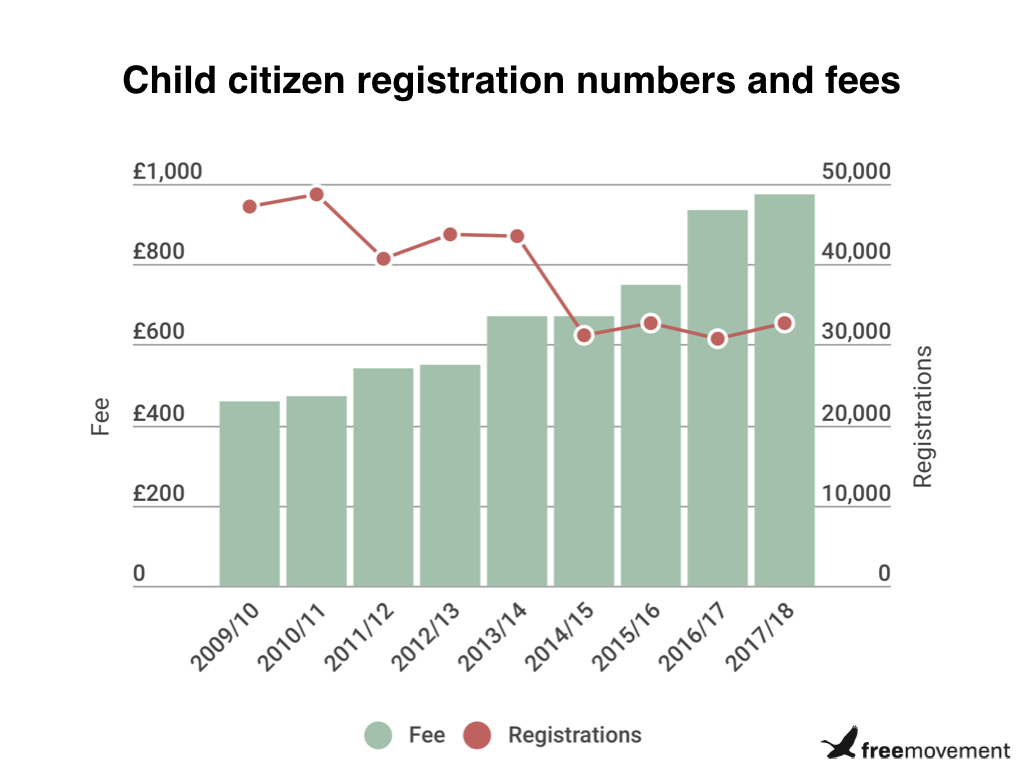

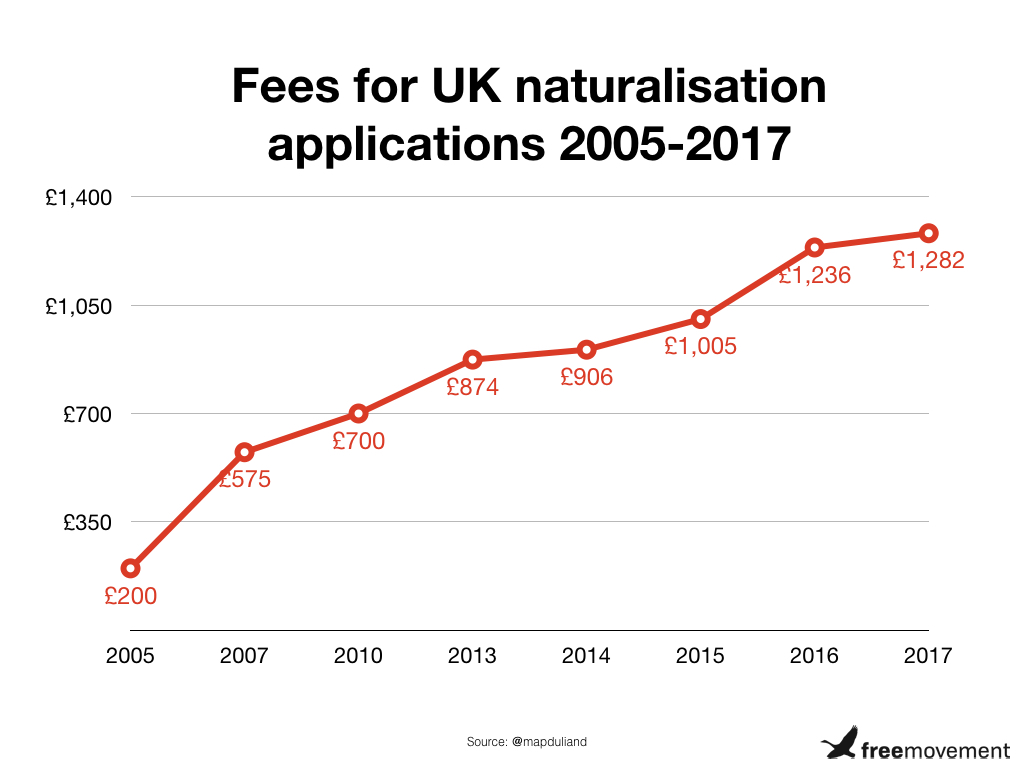

For good measure, she ramped up the cost of citizenship applications for children, almost certainly denying many children the British citizenship to which they should have been entitled.

Indeed, the cost of immigration and citizenship applications in general has skyrocketed, forcing migrants to leave the UK, borrow, scrimp and save or go illegal.

Extra legal complexity

The complexity of immigration law became infamous under Theresa May. Judge after judge has criticised the state of the law. Ordinary people simply cannot understand how the law affects them now.

The rules are such a mess now, due to changes in 2012, that an experienced immigration lawyer can barely get through an application for their own spouse.

May’s short-lived successor as Home Secretary, Amber Rudd, asked the Law Commission to try and put this right, but it is likely to be a long time before members of the public can hope to make head nor tail of the rules.

In fact, even the process of applying for a visa is now baffling, thanks to the privatisation of our immigration system through the back door. The “commercial partners” to whom the whole business has been outsourced have made a mess of things — while simultaneously trying to sell paid extras to visa applicants at every turn, turning the visa application process into a Ryanair ticket purchasing saga.

Human rights restrictions

What happens when a court finds that your removal from the UK would breach your human rights? Welcome aboard the ten-year Home Office cash train, setting you back over £10,000 excluding legal fees. The cause: Theresa May changing the rules so that those with human rights visas now have to wait ten years instead of the usual five before getting settlement, paying to renew their temporary visa all the while.

To justify attacks on human rights, she famously invoked the case of a migrant who resisted removal from the UK because of his human right to stay with his pet cat. That, of course, wasn’t true.

Fewer business visas

Theresa May even introduced a cap on skilled migrants. That’s right: she stopped skilled migrants like doctors and IT specialists from coming to the UK even when they could not be recruited locally.

It was — and remains — nuts.

This has been matched by scrapping the rules allowing graduates of British universities to remain in the UK to work (subsequently re-introduced to some limited extent under intense pressure) and the repeated refusal of business people and entrepreneurs on highly technical grounds.

Brexit

And, of course, there’s Brexit. One of May most lasting and damning legacies may well be forcing EU citizens to apply to the Home Office for permission to remain in the UK after Brexit, which will leave probably hundreds of thousands illegal after the deadline.

[ebook 90100]EU citizens were also forced to complete additional paperwork to qualify for British citizenship from 2015 onwards. The added complexity caused many to be refused and lose the huge application fee they had been forced to pay.

Also on May’s watch was a huge increase in the number of EU citizens detained in the UK, due to her illegal policy of rounding up suspected homeless EU citizens.

The simple spite

There is also what I can only describe as plain spitefulness to migrants. She seemed to be obsessed. First there were the “Go Home” vans, then the “deport first, appeal later” law under which migrants can only appeal against a decision to remove them from the UK after they’ve been removed, making it far harder to fight their case. The Supreme Court found that this had been implemented unlawfully.

So too the English language testing scandal. Only today, the National Audit Office found the Home Office presumed guilt and lacked expertise to verify cases. May’s legacy is toxic, right to the last.

Theresa May’s policies were never based on evidence. They were never going to “work” on her terms. The public was only ever increasingly alarmed by immigration as an issue rather than reassured, and the net migration target never came even close to being met.

What was the point of all this, then? Standing back, it is hard to see it as anything other than hostility to migrants because they were migrants.

Thanks to John Vassiliou for suggesting additional material for this blog post, now incorporated in an update.

SHARE