- BY colinyeo

The rise of modern banishment: deprivation and nullification of British citizenship

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Table of Contents

ToggleTo deprive a person of their citizenship on the grounds of their behaviour or opinion is to cast them out of society. It is a power of exile or banishment.

In Roman law, the punishment of “proscription” was civic and literal death, unless the person went into exile. It would be used only in cases of crimes against the state itself. Cicero did not make it as far as exile. As he fled he was summarily but lawfully executed, his property confiscated by the state and his head and hands severed and publicly displayed in Rome.

Taking away from a person their citizenship is the closest modern equivalent we have to expressing that level of disapproval and repugnance for a person’s actions.

The modern, technical, less evocative language of “deprivation of citizenship” barely attracts any interest at all (with commendable exceptions, such as this week’s investigation by the Middle East Eye). This complacency is reinforced by the watered-down and anodyne nature of the legal power, which is now on the face of it directly equivalent to that for the deportation of an alien. If anything, the protections for British citizens against being stripped of their supposedly precious citizenship appear inferior to the protections available to settled foreign nationals against deportation.

The rise of citizenship stripping

Until 2006 the power to deprive a person of British citizenship on the grounds of behaviour was almost moribund, having been used against perhaps a handful of Russian spies. But in July 2016 the Bureau of Investigative Journalism reported that Theresa May had as Home Secretary used the public good deprivation powers against 33 individuals since May 2010.

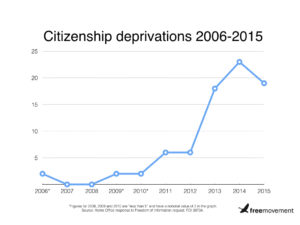

According to a Freedom of Information request by the author, the total figures are as follows:

The figures provided for 2006, 2009 and 2010 were actually “less than 5” but are represented in the chart with “2” as a nominal alternative.

There are two separate legal powers used to effect these deprivations.

The first is section 40(2) of the British Nationality Act 1981, which permits deprivation where the Secretary of State “is satisfied that deprivation is conducive to the public good”.

The second is section 40(3) of the British Nationality Act 1981, which permits deprivation where the Secretary of State is satisfied that the registration or naturalisation was obtained by means of—

(a) fraud,

(b) false representation, or

(c) concealment of a material fact.

The totals for the period 2006-2015 were according to the FOI request as follows:

Section 40(2) | Section 40(3) | Total |

36 | 45 | 81 |

A breakdown of the use of these separate powers by year is not available.

The figures do not reveal the other form of citizenship stripping which has evolved in modern times: the so called “nullification” of citizenship. This process is used where the Home Office alleges that a person used a false identity to acquire citizenship.

Null and void

Until the Supreme Court addressed this question at the very end of 2017 in the case of R (Hysaj & Ors) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2017] UKSC 82, it was rather hard to distinguish between a case in which nullification would be used or deprivation.

Essentially, the Home Office would pursue nullification action where there was an alleged deception over the identity of the person concerned. According to Home Office policy guidance (not updated at the time of writing), nullification was used where the person concerned:

1. Is not the intended recipient of the grant, for example because he or she used used a false name, date or place or birth

2. Has created an entirely false identity

3. Is using someone else’s identity

4. Was already a British citizen by birth but later applied for registration or naturalisation

In Hysaj, the Supreme Court held that nullification should only be used in cases where one person impersonated another in order to falsely claim eligibility for British citizenship. Other cases involving deception should be pursued using the statutory deprivation power.

The route by which a person’s British citizenship is removed from them is not simply a matter of dry procedure; it has profound consequences for the interim personal status of the person and his or her family members and the means of legal challenge:

| Nullification | Deprivation |

| The person never held British citizenship at all. This may affect the status of family members. For example, if a spouse applied for naturalisation on the basis of that person’s status, the spouse’s status may also be under threat. If a child was thought to have been born British because it was thought the person was British, the child may not be British at all.In such cases, British passports can be and are cancelled. There is no right of appeal but an application for judicial review can be pursued on limited lawfulness grounds. | The person was British but ceases to be so when the deprivation order is made. This does not have status implications for family members.There is a right of appeal under section 40A of the British Nationality Act 1981 or section 2 of the Special Immigration Appeals Commission Act 1997. The first of these is a full merits appeal including consideration of the reasonably foreseeable consequences of deprivation (i.e. whether forced to leave UK or not) but appeals to SIAC are on lawfulness grounds only. |

As noted in the table above, the situation of family members of a person whose citizenship is nullified can be difficult where they have later obtained British citizenship on the basis of the family relationship.

Following on from the Hysaj decision, the Home Office is reviewing and withdrawing a considerable number of recent and historic nullification decisions. The effect of withdrawal of the decision in nullification cases is probably that the person concerned continues to enjoy the British citizenship that he or she thought he or she had lost. This may well have an impact on their current immigration status, their right to enter and remain in the UK and on family members. Many such affected individuals will no doubt face deprivation action in due course, but this only serves to confirm that the person remains a British citizen until a final deprivation order is made.

Deception and deprivation

In cases where deception prior to naturalisation or registration comes to light later, deprivation will be considered by the Home Office, for example where:

1. false details were given in an asylum claim or an application for leave which affected the person’s capacity to meet the residence and/or good character requirements for registration or naturalisation

2. there were undisclosed convictions or other information affecting capacity to meet the good character requirement

3. a marriage is later found invalid or void which would have affected eligibility

When it comes to exercise of the deception deprivation power, paragraph 55.4 of the policy guidance sets out several definitions, including:

55.4.1 “False representation” means a representation which was dishonestly made on the applicant’s part i.e. an innocent mistake would not give rise to a power to order deprivation under this provision.

55.4.2 “Concealment of any material fact” means operative concealment i.e. the concealment practised by the applicant must have had a direct bearing on the decision to register or, as the case may be, to issue a certificate of naturalisation.

55.4.3 “Fraud” encompasses either of the above.

The policy makes clear that the impugned behaviour must be directly material to the decision to grant citizenship. See paragraph 55.7:

55.7.3 If the fraud, false representation or concealment of material fact did not have a direct bearing on the grant of citizenship, it will not be appropriate to pursue deprivation action.

55.7.4 For example, where a person acquires ILR under a concession (e.g. the family ILR concession) the fact that we could show the person had previously lied about their asylum claim may be irrelevant. Similarly, a person may use a different name if they wish (see NAMES in the General Information section of Volume 2 of the Staff Instructions): unless it conceals criminality, or other information relevant to an assessment of their good character, or immigration history in another identity it is not material to the acquisition of ILR or citizenship. However, before making a decision not to deprive, the caseworker should ensure that relevant character checks are undertaken in relation to the subject’s true identity to ensure that the false information provided to the Home Office was not used to conceal criminality or other information relevant to an assessment of their character.

In practice, there are few reported cases of deception deprivations. Most cases involving deception involve fundamental questions of identity and are dealt with as nullification cases.

Deportation, deprivation and “conducive to the public good”

The original incarnation of the deprivation power in the British Nationality Act 1981 was very similar to the equivalent power under the British Nationality Act 1948 and therefore could be said to have been in place for decades.

Originally the BNA 1981 set out what is now the public good deprivation power as follows, at section 40(3):

Subject to the provisions of this section, the Secretary of State may by order deprive any British citizen to whom this subsection applies of his British citizenship if the Secretary of State is satisfied that that citizen—

(a) has shown himself by act or speech to be disloyal or disaffected towards Her Majesty; or

(b) has, during any war in which Her Majesty was engaged, unlawfully traded or communicated with an enemy or been engaged in or associated with any business that was to his knowledge carried on in such a manner as to assist an enemy in that war; or

(c) has, within the period of five years from the relevant date, been sentenced in any country to imprisonment for a term of not less than twelve months.

The power only applied to those who acquired British citizenship by registration or naturalisation; British citizens by birth could not be deprived of their citizenship.

Subsection 40(5) then stated that the power should not be used unless the Secretary of State was satisfied that it was not conducive to the public good that that person should continue to be a British citizen and that the person would not be rendered stateless. At that time, the public good was more akin to an additional protection, and restraint on exercise of the power, than a threshold for deprivation.

The key deprivation power now, put in place by the Immigration, Asylum and Nationality Act 2006 as of 16 June 2006, is set out at section 40(2) BNA 1981:

The Secretary of State may by order deprive a person of a citizenship status if the Secretary of State is satisfied that deprivation is conducive to the public good.

The current test to be met to justify stripping a British citizen or his or her citizenship is therefore, at least in terms of the legal language in which it is expressed, exactly equivalent to the power to deport foreign nationals set out in the Immigration Act 1971 at section 3(5):

A person who is not a British citizen is liable to deportation from the United Kingdom if … the Secretary of State deems his deportation to be conducive to the public good.

Deportation involves removal from the UK and exclusion for the duration of the order. The Immigration Rules provide that a deportation order will normally be maintained for ten years. An application for revocation can be made before the ten-year period expires and can be granted on an exceptional basis.

In contrast, deprivation of citizenship is permanent.

There are additional legal provisions in effect mandating deportation in some defined circumstances and exempting a person from deportation in other circumstances. Under the UK Borders Act 2007, any sentence of imprisonment of 12 months or more will trigger consideration of deportation action. Exceptions are built into that Act, though – for example if deportation would breach the person’s human rights. Further, more detailed exceptions based on relationships with a spouse and/or child and long residence are built into the Immigration Rules and Part 5A of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

[ebook 57266]There is no equivalent in deprivation cases to the automatic trigger of consideration, but nor are there any statutory exceptions set out for deprivation cases. While it would be surprising and illogical for the Secretary of State to pursue deprivation action against a British citizen for behaviour which would not trigger deportation if committed by a foreign national, the bare language of statutory power itself would seem to allow for this perverse outcome.

One might expect a significantly higher hurdle to be met to justify stripping a citizen of his or her rights compared to deporting a foreign national. Because of the statutory exceptions, it could even be argued that the protection against deportation is superior to protection against citizenship deprivation.

It is not necessarily correct to compare the two powers merely on the basis of the words “public good” without consideration of the context in which they are deployed, however. It can be argued that the concept of “public good” is very different in the context of deprivation of citizenship compared to deportation, particularly if it is recalled that in the original version of section 40 the public good test was an additional restraint on the Secretary of State. Public good might be said to include the public good in maintaining citizenship as a special status and protecting citizens against deprivation of their fundamental status except in extreme cases of crimes against the state.

This is not the preferred analysis of the Home Secretary, it would be fair to say. Worryingly, these arguments have not been articulated before the courts in the – still relatively limited – number of public good deprivation cases that have come before them. These cases (and others, on deception and nullification) are considered in full in the Free Movement training course on deprivation of citizenship for those who are interested.

A right or a privilege?

Some conceive of citizenship as a right, albeit by its nature available only to a finite number of people. It is considered a special and protected status whose value lies in part in its almost indelible nature. Citizenship is the expression of the common bonds which bind society together; depriving a citizen of their status is almost a common societal failure as much as a personal one by the person concerned. Where deprivation becomes necessary it is because an individual has committed crimes against the state.

For others, citizenship is perceived as a privilege to be enjoyed only by “suitable” individuals. Indeed, then Immigration Minister Mark Harper, when introducing further legal amendments to citizenship deprivation powers in 2014, explicitly stated that “citizenship is a privilege not a right”.

For those who subscribe to this way of thinking, the preciousness of citizenship lies partly in its fragility, as if it were an antique vase. The conceptual and practical problem with this approach is that the vast majority of citizens acquire their status through the accident of birth. More active and extensive use of citizenship deprivation powers is the proposed solution.

Since 2002 the government of the United Kingdom has amended and re-amended nationality law to make deprivation of citizenship easier to achieve. Since 2010 there has been a sharp increase in use of this amended and expanded legal power. The conception of citizenship as a revocable privilege is very much in the ascendancy and use of the deprivation power is only likely to increase in the foreseeable future.