- BY CJ McKinney

Six things we learned about the English language testing scandal from today’s NAO report

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

The National Audit Office, a government watchdog, has released an authoritative report on the long-running English language testing scandal. The discovery in 2014 that there was widespread cheating on the English tests required for UK visas led to a Home Office crackdown affecting tens of thousands of people, many of whom protested that they were innocent.

The NAO’s assessment suggests that they were right. The heavy-handed official response — “deport ’em all and let God sort them out” — took little account of the potential for wrongful accusations. The overall assessment of NAO head Sir Amyas Morse reads, in its entirety:

When the Home Office acted vigorously to exclude individuals and shut down colleges involved in the English language test cheating scandal, we think they should have taken an equally vigorous approach to protecting those who did not cheat but who were still caught up in the process, however small a proportion they might be. This did not happen.

Here are some highlights of the NAO’s report.

1. There definitely was cheating on English language tests

This was never like the Windrush scandal, in that at least some of those accused of cheating on these tests did it. The NAO concluded that the evidence “strongly suggests that there was widespread abuse of the Tier 4 visa system” and that “it is reasonable based on the balance of probabilities to conclude there was cheating on a large scale because of the unusual distribution of marks, and high numbers of invalid tests in test centres successfully prosecuted for cheating”.

25 people have been convicted of criminal offences for organising the cheating, and 14 more may yet be charged. “Organised crime groups” were to blame, with the report citing one ring which controlled three dodgy colleges in Manchester:

Evidence from unannounced inspection visits, computers and documents proved the fraud had taken place. The investigation found the crime group had used a set of proxy test-takers to take the [English] speaking test on behalf of people willing to pay for the service. The group was making considerable income from the fraud, charging around £750 for each [test], which would ordinarily cost £180.

2. But we’ll never know how many people actually cheated

While tens of thousands of people were accused of cheating, the NAO was not particularly impressed by the investigation process.

The American company Educational Testing Service (ETS) administered the tests and did most of the legwork in trying to sort out who had cheated on them. ETS deemed 34,000 tests invalid, and another 22,000 “questionable”. That represented 97% of all its English exams taken in the UK between 2011 and 2014.

It arrived at that figure with the help of automated voice recognition software. The idea was that candidates had been able to get someone with better English to take their oral exam.

The NAO pointedly does not accept the ETS analysis at face value. It pointed out that voice recognition technology had not been used before in this context, and there was no control group to see whether it actually worked. Independent experts who tried to assess ETS’s method of weeding out cheats “did not know what software had been used, have access to many voice recordings, or know the performance of human verifiers”. Nor could they explain why, in some cases, the supposed ringer had actually failed the test. The report concludes that

It is difficult to estimate accurately how many people may have been wrongly identified [as cheats].

3. The Home Office didn’t care if people were wrongly labelled cheats

The NAO found that the Home Office was supremely relaxed about the innocent being caught up in the ETS dragnet. It was two years before the department commissioned its own quality assurance of ETS’s system for identifying cheats.

The report also says:

We saw no evidence that the Department considered whether ETS had misclassified individuals or looked for anomalies… It had not investigated the reasons why people with invalid scores had low marks, won appeals or gained leave to remain…

The NAO, being more curious, burrowed into the evidence and found that ETS treated at least 3,700 written tests as suspicious “even though the marks suggest candidates were not fed the answers”.

It concluded that:

the Department’s course of action against TOEIC students carried with it the possibility that a proportion of those affected might have been branded as cheats, lost their course fees, and been removed from the UK without being guilty of cheating or adequate opportunity to clear their names.

4. ETS denied people the chance to clear their name

The Home Office took enforcement action of one sort or another against a whopping 25,000 people. Those who protested their innocence asked ETS for the information it used to brand them cheats, such as the recording of the suspicious oral exam. The company’s response was, it appears, unhelpful:

Even when students have had legal representation they have had difficulty obtaining all of their personal data, including the original recordings and other materials from the day of the test. Some students also had difficulties obtaining the voice clips that were used as evidence against them. Bindmans, the legal firm which has represented dozens of TOEIC students, told us that ETS had failed to provide information and documents to which the individuals are entitled.

In at least one case, ETS destroyed this vital evidence instead of handing it over.

5. Dozens of colleges lost their sponsor licences

Colleges and universities were also affected by the fallout. The NAO records that almost 100 institutions had their licence to sponsor foreign students suspended if they had a lot of students thought to have cheated on their test. Of those, 89 ultimately lost their licence (and likely had to close as a result).

Was this fair? On one hand, the immigration inspector found that the Home Office investigation of college had been “handled well”. On the other, colleges complained that they had only taken the students in the first place because they had passed a Home Office-approved test, so it was a bit rich to blame them when the test turned out to have been compromised. And in some cases, “the Department had given sponsors a ‘clear’ audit rating shortly before investigating them again with a view to suspending or revoking their licence”, according to Universities UK and the inspector.

6. Thousands of people have won TOIEC appeals

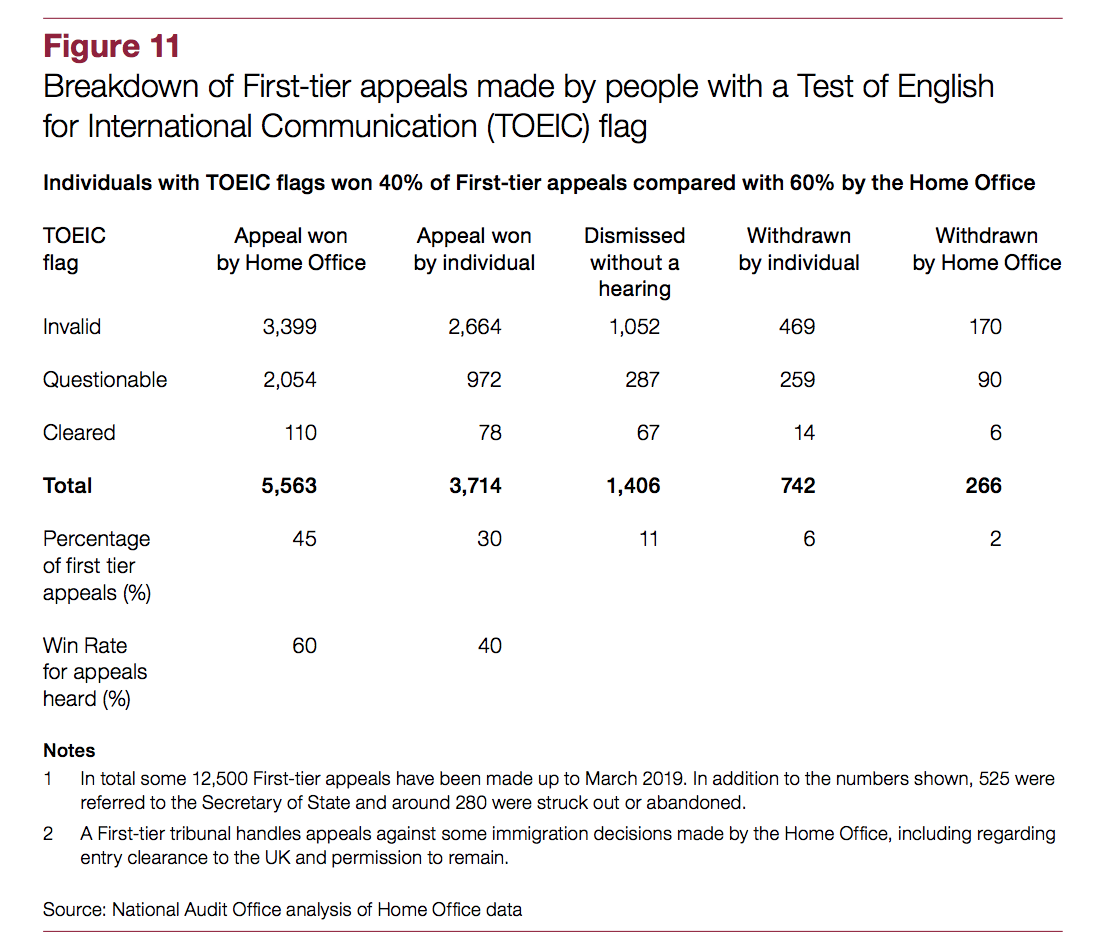

The test in question is called the Test of English for International Communication, or TOIEC. Around 3,700 people accused of TOIEC cheating have won appeals in the First-tier Tribunal, according to NAO analysis of Home Office data.

The report notes that “people usually had to appeal on human rights grounds because they could not appeal the decision directly”, implying that the figure could have been much higher had there been a direct right of appeal. Around 11,400 people caught up in the scandal subsequently left the UK.