- BY Josie Laidman

Seasonal Workers face ongoing exploitation as government shows little interest in enforcement

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Yesterday the Prime Minister announced a quota of 45,000 seasonal worker visas for 2024, “to give certainty to the horticulture sector next year, enabling them to plan ahead for the picking season”. It is billed as part of a larger package of support for British farmers. But we know that many of these migrant workers are accommodated in appalling conditions and exploited. A session of the House of Lords Horticulture Committee just last week heard extensive evidence of exploitation on the seasonal worker scheme.

How did we get here?

The Seasonal Worker scheme launched in 2019 with an initial quota of 2,500 visas each year. This figure has increased each year and in 2022 there were 38,000 visas available and a further 2,000 for poultry workers. With Boris Johnson as Prime Minister, the government said that the scheme would be extended until at least the end of 2024, but that the quota would be reduced to 30,000 in 2023 and 28,000 in 2024.

Another increase was announced in December 2022, with 45,000 visas announced for 2023 “with the potential to increase by a further 10,000 if necessary”. The 45,000 figure announced yesterday is, despite some of the rhetoric, not particularly new or exciting. The quota is being made available from earlier in the year, though, which should apparently help some farmers.

The quota announcement last December made the 10,000 additional visas contingent on farmers “improving and abiding by the worker welfare standards, including ensuring workers are guaranteed a minimum number of paid hours each week”.

What about net migration?

In her recent speech at the National Conservatism conference, Braverman said she wanted to reduce net migration. She suggested that there is “no good reason” the UK cannot train its lorry drivers and fruit pickers in order to bring immigration down.

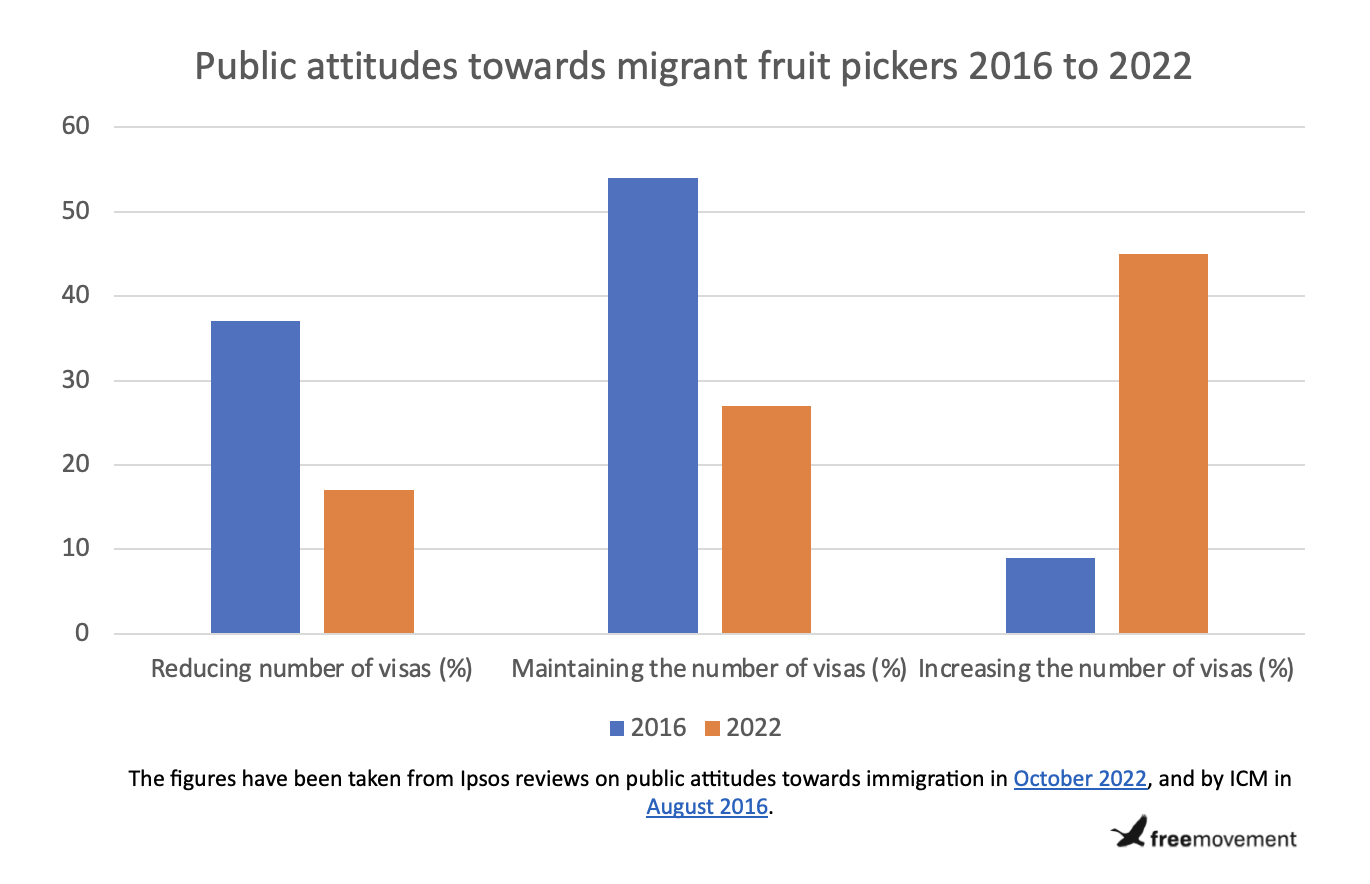

As ever, people often express a general desire for lower immigration in theory but are actually pretty relaxed about immigration in practice, aside from refugees. There is very little public demand to reduce the number of migrant fruit pickers supporting the farming industry each year, which might be partially due to greater public awareness of specific labour shortages in the industry. And perhaps because people like fruit, and they like it cheap.

The table below shows the percentages of the public that would like to see a reduction or increase in the numbers of migrant fruit pickers in the UK:

What evidence of abuse is there?

Workers recruited on the seasonal scheme are being exploited. First of all, they are paying for their own recruitment, turning them into modern day indentured labourers. Just last week, the House of Lords Horticulture Committee heard that interim report findings showed that the lowest total costs paid by Indonesian workers in order to work on the scheme in 2022 was £3,500. These sums then have to be paid off through wages.

And once they have been recruited, they have no choice but to live in appalling conditions on the farms. Only 73% confirmed they had access to a working toilet and only 39% said they felt safe in their accommodation. Another report recently released corroborated findings of substandard living conditions, where seasonal workers paid (collectively) up to £2,000 a month to live with five people in a caravan, or sharing rooms with strangers.

This second report is part of a series released by The Bureau of Investigative Journalism. The first confirmed bullying, growing debts and unsafe working conditions on UK farms and the second confirms reports from workers of being underpaid. The Committee heard evidence last week that corroborated these reports, with complaints on pay and continuity of employment being the largest areas of complaint. Several employees also reported that their employment was terminated after three months or less on their visa, which is usually granted for six months. If they have had to pay to be recruited in the first place, this leaves them in serious difficulty.

This issue is compounded by the barriers to seeking help. 28% of people did not know where to get help showing that enforcement and engagement with the sector needs to be proactive for it to have any success. These workers are also often completely absent from local authority plans and are simply not included in numbers for things like flood evacuations.

The Home Office “really needs to raise its game to assure itself that scheme operators are not perpetuating poor working conditions”, the Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration said. It is concerning that it was unable to effectively measure whether standards were being upheld or not. After 25 compliance visits the Home Office found “significant welfare issues” in nine of those visits, but it is unfortunately not clear what action was taken as a result of that information coming to light.

Only nine investigations into allegations relating to conditions on the seasonal worker scheme were conducted by the Gangmasters and Labour Abuse Authority. Two reasons were cited; that there are only 121 staff at the agency, and that workers are often scared of coming forward for fear that it will affect their immigration status, or that their employer will retaliate.

The Director of Labour Market Enforcement told the Committee that it was unlikely that any new funding would be allocated to labour enforcement because “there is no parliamentary time to create the [single enforcement] body”.

What should the government be doing?

Terminating the seasonal worker scheme with no replacement would be pretty disastrous for farmers in the short term. Bu that is by no means the only option available to the government. There are two things that could be done which would address these problems, and they could both be put into action at the same time.

One is to at least put resources into monitoring and enforcement. This is surely the bare minimum we can expect, particularly if the government is actually expanding the scheme still further. This could be cost neutral if the money was extracted from the farmers who benefit from the scheme.

The other is to end the practice of tied visas, which force the worker to either stick with an employer come what may or leave the country. Enabling workers to move between employers would give them some agency and enable them to move on from exploitative employers. In turn, we would expect employers to start treating them better in order not to drive them away.

These are not perfect solutions but they are very, very easy to implement and they would do something to address the exploitation caused by the way the scheme is currently being operated.