- BY Nicholas Reed Langen

Reaction economy: the Home Office’s use of social media

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Table of Contents

ToggleWe live in a reaction economy. The age of social media means that governments, companies, and others in the public eye are not ruled by accountants assessing their bottom line or journalists scrutinising their actions, but by voters tapping onto their screens at home. Few government departments have embraced this age as whole-heartedly as the Home Office.

The Home Office on Twitter

Its Twitter page exemplifies Bagehot’s dictum that the British constitution comprises of two parts – the dignified and the efficient. A purple-backed coat of arms serves as its profile picture, lending every tweet gravitas and nobility. For those curious enough to follow its profile, this restrained majesty is backed by brute populism, with the government’s numbered ‘priorities’ stamped down on the profile background.

The image’s entire purpose is to get the message out and to remind people both what their interests are, and that the government is doing something about them. That most people were blissfully unaware of the refugees and migrants crossing in boats before the government decided to prioritise the issue is irrelevant. So is the fact that in terms of immigration numbers, the number of people crossing the Channel is statistically insignificant. What is important is what people fixate on – and social media is the best way to bring about this obsession.

The power of media

Not only does it let the Home Office directly mould the opinions of voters, but it lets it direct the press, with most journalists, particularly for papers sympathetic to the government, content to use government press releases to guide their copy.

Statistics over the last few months bear this out. Since the government put forward its Illegal Migration Bill at the beginning of the year, and since the Home Office began its social media highlighting small boats, polling has seen illegal immigration rise as an issue in the public consciousness. In February, only 12% of people polled by Ipsos thought immigration was a priority issue. By March, its salience had increased by eight points – with immigration (particularly illegal immigration) becoming the second most important issue for Conservative voters, behind only the economy. At a time when NHS waiting lists are endless, the climate is on the cusp of breakdown, and inflation is rampant, that a third of the nation thinks the second most important issue is a few thousand desperate people in boats is astonishing.

This reflects the power of social media, and how it can be used to shape issues, to obfuscate reality, and perhaps even to manipulate the press. There is no duty of candour on a Home Office Twitter thread. The Home Office is free to pump out propaganda about how it has ‘BUSTED’ (complete with a klaxon emoji) illegal workers at a car mechanics, or, more incongruously, to brag about how it is planning to deny illegal immigrants protection from modern slavery.

Media policy, past and present

Conventional press releases were no longer seen as sufficient as long ago as 2012 when the Home Office used social media to evidence its purge of illegal migrants from the UK during Operation Mayapple. Social media campaigns show the Home Office going beyond the dirty business of quiet and competent enforcement of immigration law. Some would say it shows they are loud and incompetent by photographing and publishing raids. As we mentioned during Operation Mayapple, there is perhaps a link between volume and efficiency.

That Britain has been reduced to a nation where the government is gloating about how it is planning to expose vulnerable people to being enslaved does not worry the Home Office. Significant effort goes into these social media posts. Some posts contain photographs of enforcement, seen since 2012, and most other posts are accompanied by a vivid photoshopped graphic, often in red, white and blue, with keywords brought to the fore. An oft-repeated one emphasises that people have been ‘REMOVED’, and another turns its attention to how the boats will be stopped- ‘by not considering asylum claims by illegal arrivals’.

The fact that this fixation on deterrence has failed to even slow the tide of asylum seekers crossing Europe and camping at Calais is completely disregarded. The fact that these people are already willing to risk their lives to cross the Channel should carry with it the obvious implication that there is almost nothing that will not deter them.

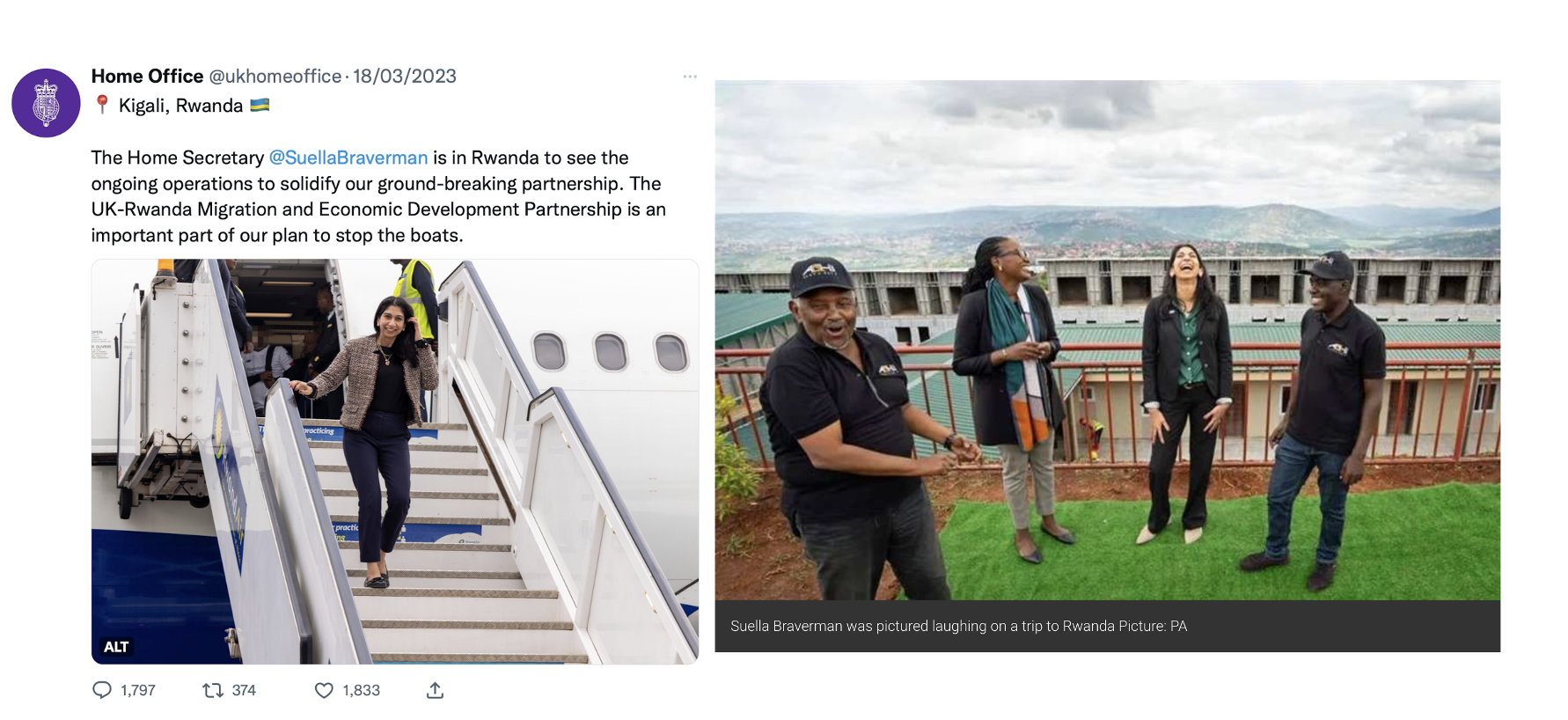

Suella Braverman’s visit to Kigali was heavily referenced across the Twitter profile. In a video that was pinned to the top of the page for a long time, a portrait-shot clip of Suella Braverman extolling how she is “delighted to be here in Kigali” to discuss the UK government’s Migration and Economic Partnership with Rwanda. A series of photos tweeted out during her visit show the Home Secretary arriving, viewing the construction of a housing estate apparently intended for this partnership, and celebrating with some cricketers who came to Rwanda as refugees from other African states. Further photos distributed to the press showed Braverman cackling, hyena-like, at the progress in the Rwanda camps, and having the time of her life with Rwandans.

On any rational analysis, showing Rwanda as a bucolic paradise should be anathema to the Home Office and supporters of this policy. But it also juxtaposes the fact that Rwanda is supposed to serve as a threat, deterring asylum seekers from risking crossing the Channel. Advertising it like a holiday resort in a travel brochure is like trying to stop flowers from growing by watering them.

Attempting deterrence (as well as enforcement) through advertising is nothing new. A pilot scheme took place between July and October 2013 in six London boroughs to test whether different communications could encourage any increase in voluntary departures. The scheme was called Operation Vaken. It included mobile billboards, postcards in shop windows, adverts in newspapers and magazines, and leaflets and posters advertising immigration surgeries. Around 60 people voluntarily departed the UK as a result of this scheme and the communication methods used cost much less than enforced removal: £15,000 for the average single enforced removal in 2013, compared to the total cost of Operation Vanken, £9,740. This scheme was often referred to in the press as Theresa May’s ‘go home’ vans.

It shouldn’t come as a surprise that the latest version of the ‘go home’ vans comes in the form of more social media posts. Many suggested that the vans had a ‘distinctly unsavoury association’, with a crude populist approach, used as an aid during the Conservative-Lib Dem coalition to keep Ukip at bay. In order not to be seen as a soft touch, the government would have to convince voters it was reducing the number of immigrants, and the Home Secretary was almost obsessively determined to reduce net migration figures. The Home Office’s use of media has evolved a little with the times but it remains nothing more than a political strategy, aided by Home Secretaries obsessed with the figures ahead of crunch points in the political cycle.

Government policy dictated by media

Hostility and antagonism are still the order of the day. But this is amplified by the government’s new tactic of banning critical news organisations from important trips and press opportunities. By selectively picking which outlets travelled with her to Rwanda (including excluding the BBC and the Guardian) Braverman exemplifies the dangerous attempts by recent governments to marginalise and exclude journalists attempting to hold the government to account by telling the other side of the story, or by asking difficult questions.

Some suggest there is a pattern here. The Rwanda plan entirely bypassed Parliament. The new Illegal Migration Bill is being expedited to minimize debate. And it aims to prevent scrutiny by the courts. This is a government which wants to avoid any legal or democratic constraints: and this unwritten policy is exemplified even in just the way it handles its interactions on Twitter.

The Home Office might luxuriate in the freedom to tweet out, but it doesn’t give the same freedom to other institutions – no matter the accuracy of their content. The Windrush community engagement fund was established in the aftermath of the scandal in the hope of repairing relations between the communities affected by the government’s immigration policies and the Home Office. After this year’s funding was approved by civil servants, the Home Secretary’s office blocked the funding to two groups, after political advisers raised concerns about them being critical of the Home Office on Twitter. The issue spiralled out of control, with the grant process delayed by discussions about the exclusion of the groups, and with the Home Office reportedly cancelling the scheme for 2022-23.

Home Office policy is always sensitive terrain. Questions of national security and citizenship resonate with citizens in a way that questions over tax rates or healthcare do not. It goes to our atavistic instincts about who belongs and who does not, and lets some people be ‘othered’ and ostracised punitively from society. Through social media and the press, the Home Office exploits this vulnerable aspect of society, antagonising peoples’ fears and then using their response to justify brutal policies. What we are left with is a self-perpetuating cycle – one that can only be broken by toppling the departmental apple cart.

2 responses