- BY Naomi Hanrahan-Soar

Comment: Boris’s science visa promises ring hollow

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Boris Johnson announced seemingly sweeping changes to the UK immigration system for scientists on 8 August 2019. Behind the usual rhetoric about attracting the “brightest and the best”, the reality is a lot less dramatic and potentially a lot less meaningful for the future of science in the UK. If we want scientific talent and creativity to flourish, we need to genuinely open up the immigration system.

What is Boris saying he will do?

- Establish a new fast track visa for scientists and researchers

- Remove the cap on Tier 1 (Exceptional Talent) visas

- Expand the number of universities and research institutes that can endorse candidates

- Allow for “automatic endorsement”, so that some candidates will not need a specific organisation to endorse them at all

- Remove the need to have a job offer before arriving

- Provide an accelerated path to settlement in the UK (three years rather than the usual five)

- Allow dependants to work freely in the UK

Now let’s debunk a few of those:

- A Home Office fact sheet makes clear that this is not a brand new type of visa, but rather an expansion of the existing Tier 1 (Exceptional Talent) route

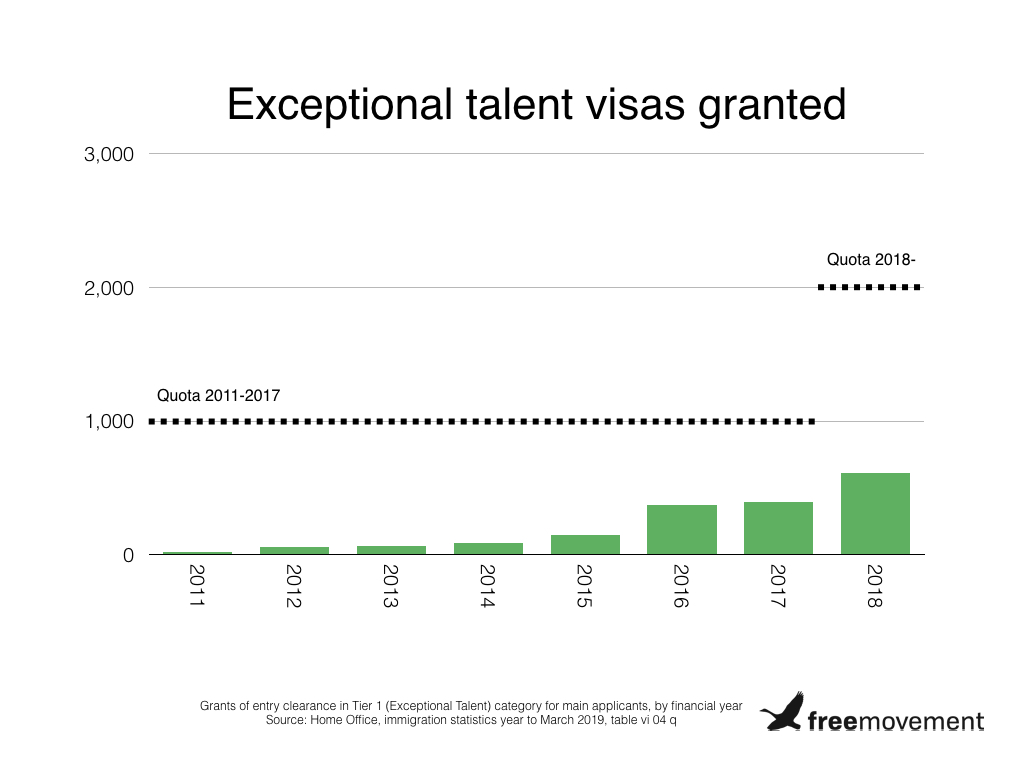

- The existing caps on the Exceptional Talent visa have never been met; removing the cap is logical (why cap the brightest and best at all?) but has little practical implication

- People applying under Exceptional Talent don’t need a job offer

- Their dependants can already work freely in the UK (with minor exceptions)

- Some Exceptional Talent visa holders can already settle after three years.

So far, so much bluster. The press release also includes the glaring caveat that all these ideas are “options which could be discussed”.

What might actually change?

Expanding the pool of organisations that can endorse people for an Exceptional Talent visa — at present there are only five — could be significant. And if the endorsement criteria are made clear enough to allow for automatic endorsement, that would indeed be very welcome.

This would require significantly reforming the existing criteria for endorsement. At present they are very difficult to meet and are also quite subjective. Individuals need to evidence that they have proven success in their field, an internationally recognised award and be supported by an eminent individual within the UK who is familiar with their work.

The Royal Society has a quota of 250 places per year which has never yet been met. Tech Nation, which has granted the most endorsements, only grants about half of all applications made to them. In total, since the end of 2013, they have granted just over 950, or fewer than 190 each year.

The visa does have value. But there is still a sizeable gap in the visa market for options that allow highly skilled individuals to build their careers in the UK without being tied to one employer.

This hardly makes up for Brexit

Boris is clearly worried by recent statements from the likes of the Wellcome Trust that a no-deal Brexit would be a threat to UK science. Hence why he has gone on the offensive and announced he wants the UK “to be the greatest place for science”.

He recently gave a speech at Culham Science Centre in Oxfordshire citing Sir Andre Geim’s work discovering graphene as an example of the great scientific achievements in the UK which he wants to encourage. Sir Andre told the Times the following day that his Russian partner in that discovery already left the UK for Singapore – apparently as a result of the EU referendum and the implications of Brexit for the scientific community.

The BBC reports that half of the researchers in the 211,000 scientific workforce in the UK are from the EU. Also, half of the international academic talent in UK universities, the education system that makes Britain famous worldwide, are from the EU — which is also the UK’s largest research collaborator. Restricting access to that pool of talent after Brexit could severely affect the ability of our scientific and technical community to function, let alone prosper. Tier 1 (Exceptional Talent) simply cannot make up those numbers of talented people in its current form.

Reform of ordinary work visas would be more effective than expanding a niche route

Boris is right to say that we should not restrict skilled visas only to those with a job offer. But Tier 2 (General), the main visa for skilled workers wishing to come to the UK, currently does just that. It also has a minimum salary of £30,000 per annum, making Tier 2 unsuitable for some scientific researchers who may earn below that and who may be engaged on a series of short-term projects with gaps between employment.

The Tier 2 minimum salary also ensures that migrants are more likely to stay in London rather than working in the regions where salaries are lower. Those same regional areas are the ones with the lowest immigration levels and the highest proportion of Brexit voters. It seems counter-intuitive, but increasing immigration to those areas is likely to help lift the opportunities locally and to diminish potential fear of foreigners by giving them a friendly face. Many parts of the UK want more immigration — such as Scotland, where MPs actively lobby to make immigration easier.

Once here, fewer restrictions should be placed on those under the Tier 2 skilled worker visa. That visa only permits very limited work beyond the job the visa is granted for. But the growth of portfolio careers means more entrepreneurs start their business whilst keeping a full-time job until the new business can sustain them. In effect, the rules limiting work outside your day job stifle entrepreneurship and hard work.

Further, the Tier 2 visa route includes, on top of other visa charges, a Skills Charge levied on employers at £5,000 for a five year visa. This was introduced as a policy to deter employers from hiring outside the settled labour market if they don’t need to. Why not waive that if the visa is going to one of these priority industries? Why seek to encourage international talent in rhetoric, but actively deter them financially?

Boris is actually on point – we do need more exceptionally talented individuals. But we won’t get them by bombastic announcements alone.