- BY Colin Yeo

What is in Welcome to Britain: Fixing Our Broken Immigration System?

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

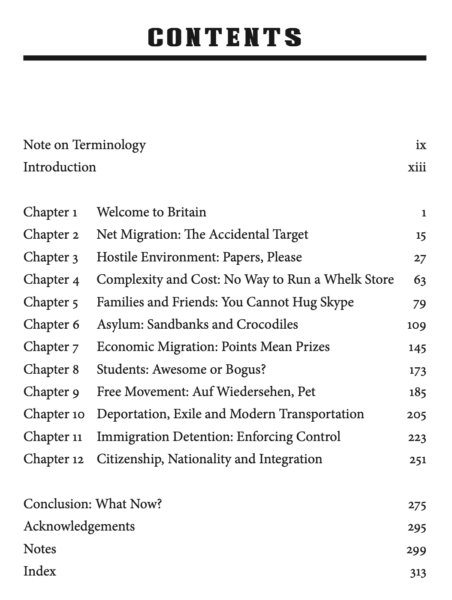

My book Welcome to Britain: Fixing Our Broken Immigration System launches today. I was delighted to see it getting some coverage in the Observer yesterday. If you haven’t already you can order a copy from Waterstones, Amazon or from your local bookshop. You can also order a signed copy directly from us (although there will be a bit of a delay getting it to you as I’m still waiting for a delivery from the warehouse and have over 100 to get through once they do arrive!).

Those who have taken an early look at the book have liked it so far:

We’re holding an online event at 4pm today, in which Satbir Singh from JCWI will be asking me questions about the book. We’ll be live-streaming that on YouTube and you can sign up here.

I thought it might be helpful to give you an idea of what is actually in the book…

Immigration policy past and present

The first chapter of the book outlines very briefly the mixed history of immigration law and policy since the start of the twentieth century, with a few more historical references thrown in for good measure. Perhaps surprisingly, the twentieth century began with no immigration laws at all and remained remarkably open until 1962. However, a mainstream political consensus to severely restrict immigration rapidly emerged and lasted until around 2000, when Tony Blair’s Labour government instituted an active economic immigration policy for the first time in decades. The growth in the number of asylum claims from the mid-1990s onwards, before a rapid and unplanned increase in migration from new members of the European Union from 2004, enabled immigration to be rapidly repoliticised as an issue. Ultimately, it would contribute its part to Labour’s loss of office and the subsequent Brexit referendum result just over five years later.

The second chapter takes a long, hard look at the evolution and effect of the net migration target. As the primary driver of immigration policy for a decade, this target was hugely influential. Widely thought to have been announced by David Cameron when he was Leader of the Opposition in January 2010, the idea of introducing a specific numerical limit to immigration actually dated back to the Conservative Party manifesto of 2005. Once he took over as leader after that election, Cameron was careful never to state a specific number and proposed to apply the limit to non-EU immigration only. This was too nuanced, though, and from 2010 onwards the perception gradually spread that a target had been set, restricting net migration to 100,000, to be applied to all forms of migration, EU and non-EU alike. Cameron had never said nor intended this, yet the perception was so widespread that he and his Home Secretary, Theresa May, felt bound to embrace it.

In the third chapter I turn to the signature immigration policy of Home Secretary and later Prime Minister Theresa May: the hostile environment. This is a system of laws and regulations requiring private citizens and public servants to carry out ‘papers, please’ immigration status checks on one another. The primary purposes of this are supposedly to deter unauthorised migrants from arriving and to force those already resident to leave. A secondary purpose is to save money. There is no evidence, however, that it achieves any of these aims, and there has been no attempt to monitor success or failure. In reality, the policy looks more like a moral crusade to make life miserable for unauthorised migrants than a serious attempt to reduce the number of them living in the UK. It has been an unmitigated public policy disaster that brought the Windrush scandal bubbling to the surface and continues to do huge violence to race relations in the United Kingdom.

The last of the thematic chapters, Chapter 4, looks at the complexity and cost of the current immigration system. Described by top judges as ‘byzantine’ and an ‘impenetrable jungle’, immigration law grew rapidly from the 1990s onwards. An ever-changing web of treaties, laws, regulations, rules and policies has obscured the meaning and purpose of the law, generating huge volumes of litigation and making it all but impossible for a migrant to navigate the system without a lawyer. Meanwhile, the cost of making an application has shot up to over £3,000 per person in some situations, putting lawful status beyond the reach of many and causing social hardship and disadvantage even to those who are able to find the money from somewhere. Individual changes and tweaks to the rules may seem incompetent or unintentional when taken in isolation, but the trend is clear and therefore deliberate. A simplification project has belatedly been re-launched, but it would be naive to think that the complexity has not become a tool of wider immigration policy.

I then turn to individual policy areas for different categories of migration.

Immigration law in action

Chapter 5 takes a look at family migration rules and in particular how they have changed since a major reform package in 2012. Families have been torn apart by these rules, with any spouses or partners earning less than £18,600 forced to make an invidious choice between emigrating, splitting apart or living illegally in the UK. Even before coronavirus, around 40 per cent of the working population of the United Kingdom could not afford a spouse visa, with women, ethnic minorities, the young, the old and those outside London being particularly disadvantaged. The rules on children are outdated and fail to take account of the preferences of the parents, the child’s own opinion or the child’s best interests. It is now virtually impossible to sponsor a dependent parent, forcing those whose parents require care either to pay for impersonal treatment abroad or to re-migrate to provide it themselves. Family visits to the UK are unavailable to many because, since the abolition of appeal rights in such cases in 2014, a visit visa refusal is usually now final and permanent. The option of relocating together as a family to a nearby European Union country will also be lost at the end of the Brexit transition period, along with the free movement rights of British citizens. The reforms have been driven by futile attempts to meet the net migration target, a desire to maintain the existing ethnic composition of the population and, at the very least, wilful blindness to the effects on those concerned.

Chapter 6 traces the recent history of asylum policy. Media, political and public hostility to refugees prevents many genuine refugees from reaching the United Kingdom but does not stop them from trying, while deterrence and the elimination of ‘pull factors’ have proved to be ineffective. The borders have been successfully strengthened, but the price of this security is paid by the refugees who die on their journeys. Over 20,000 have drowned in the Mediterranean since 2014. Following the increase in asylum claims that first began in the 1990s, a culture of disbelief has developed at the Home Office, with the success rate for asylum claims transformed from 87 per cent in the early 1980s to just 4 per cent by the next decade. While there are still major problems with Home Office decision-making, particularly concerning wishful thinking about how politicians and officials would like real refugees to behave as opposed to how they actually behave, nearly 40 per cent of asylum seekers are now recognised as refugees by the department. Once appeal outcomes are taken into account the total is more like 55 per cent. The deterrent policies that make life miserable for asylum seekers and that permanently disadvantage them if they are allowed to remain were designed at a time when it was thought the majority would not be permitted to do so. In reality, the majority of asylum seekers win their cases, so it would make sense to help them start to integrate and rebuild their lives as soon as they arrive. At the very least, asylum seekers should be treated with far more respect and generosity than that with which they are currently greeted when they land on our shores.

The focus of Chapter 7 is economic migration. The points-based system, introduced from 2008 onwards, was the culmination of multiple attempts to inaugurate a positive economic immigration policy and ‘modernise’ the various routes by which migrants could come to work in the UK. The purpose was to boost productivity, prosperity and public finances and the tests for success were whether the new system would be ‘operable, robust, objective, flexible, cost effective, transparent, usable’. It turned out to be none of those things. The Home Office was massively over-ambitious in trying in effect to automate the decision-making process and eliminate subjective judgment entirely. With the change in government after the 2010 election, the department retrenched from a positive economic immigration policy, while it continued to pay lip service to the concept in public. Sweeping subjective judgments were reintroduced but the intricate framework of now obsolete objective rules remained in place. Economic migration can bring real benefits domestically and internationally, but its language is often starkly utilitarian. When migrants are seen as a natural resource to exploit rather than as human beings with their own lives and families, there is a danger that they become a servant class.

Chapter 8 moves on to discuss international students. Ignored for decades before being seen as an opportunity, then more latterly being viewed as a threat, successive governments have swung between seeking to attract international students and trying to deter them from coming. However, the evidence is overwhelming that international students boost local economies and cross-subsidise domestic students and research. As much as 13 per cent of all university income is derived from the high fees that they pay. The efforts to deter foreign students from studying in the UK were founded on faulty data regarding how many students leave the country at the end of their studies and a perception that too many students were somehow ‘bogus’. In reality, many were ripped off and then abandoned by the private, unregulated colleges and test centres that the government permitted to flourish in the early days of the points-based scheme. The evidence suggests that 97.4 per cent of international students leave the UK at the end of their studies, while those who do remain add skills and productivity to the economy and diversity to our national life. Students should be saluted, not shunned.

Chapter 9 homes in on EU free movement laws. I take a wistful look back at how ordinary British citizens enthusiastically embraced their European free movement rights and how the country’s departure from the European Union was engineered despite this. Euroscepticism began as an esoteric, narrow vision of the meaning of national sovereignty that had little popular resonance. The invention of populist Euromyths and the concept of benefit tourism in the 1990s, combined with the surge in migration from the EU following its expansion in 2004, transformed Eurosceptism into a powerful force. As Prime Minister, David Cameron woefully mishandled the issue. Setting impossible expectations with promises that tightening welfare benefit eligibility rules would magically deter the non- existent benefit tourists, he then pledged to renegotiate the terms of British membership of the European Union with no realistic prospect of being able to deliver on this either. The outcome was Brexit. EU citizens in the UK are now being forced to apply to the Home Office just to remain lawfully resident in the country and it is likely that tens or even hundreds of thousands will be left living here unlawfully when the deadline for applications passes. Meanwhile, British citizens are yet to grasp what departure from the European Union means for visiting, studying, living or retiring in European countries.

Deportation is the subject of Chapter 10. Often more akin to exile and nineteenth-century-style transportation, any criminal sentence of twelve months or more now triggers the automatic expulsion of non-citizens, even for those born in the United Kingdom or brought here as small children. Statutory exceptions have deliberately been so narrowly drawn that virtually no one can rely on them. The problems and difficulties that have arisen with deporting foreign national offenders were never about the law, though. They were the result of incompetence at the Home Office and the setting of impossible expectations by politicians. Any semblance of humane flexibility has been lost as a consequence, yet the number of high-risk foreign national offenders removed has fallen and the number of low-risk EU citizens has risen. Deportation law, procedure and prioritisation all need to be rethought.

Chapter 11 turns to the sharp end of immigration law: detaining unauthorised migrants and enforcing their removal. The number of beds in immigration detention centres was massively expanded by the Labour governments of 1997 to 2010 but even then their number never came close to reaching the capacity needed genuinely to enforce immigration laws. There is estimated to be a population of between 600,000 and 1.2 million unauthorised migrants, all of whom are potentially eligible for removal. Whether a particular migrant is detained and removed is a matter of luck. In this context, any decision to detain is inherently arbitrary. The detention system does not, in fact, enforce immigration laws and there is no evidence to suggest it has any meaningful deterrent effect. I argue that its only real function seems to be either moral or political. Meanwhile, the human cost to those migrants who experience indefinite immigration detention can be awful. While the number of migrants detained every year has started to fall as the Home Office has begun to rethink its approach, the number of vulnerable immigration detainees actually seems to have increased.

Finally, Chapter 12 considers the possible legal meanings of being ‘British’, the rights and responsibilities of being a British citizen and then the possible routes available to those wishing to become British, whether that be through birth, descent or application, and the growth in the phenomenon of citizenship-stripping. On closer inspection, it turns out that British citizenship is little more than a revocable form of immigration status. For a time, citizenship was linked to migrant integration, but it was never clear whether it was supposed to help facilitate integration or to reward it after the event. Citizenship policy has been driven by the conception of citizenship as a privilege not a right, by the desire to keep numbers of new citizens small and by a related racial dimension. The outcome is a large population of long-term resident non-citizens, some of whom have lawful status and some of whom do not. They are excluded from full participation in national life, for example through being unable to vote in parliamentary elections. Citizenship law and policy should be reformed to ensure that migrants and long-term residents are both able and encouraged to become citizens.

Making things better

In the conclusion I argue that we cannot and certainly should not go on as we have. We need to move on from seeing immigration as a ‘take it or leave it’ contractual transaction in which the United Kingdom can dictate the terms of entry and stay no matter how harsh or unfair those terms might be. Instead, we should see newly arriving migrants as citizens-in-waiting who will join and be part of our society. The fact is that most migrants who arrive in the United Kingdom to work, join family members or seek sanctuary will be allowed to stay. It is wrong to disadvantage them deliberately from the start, and wrong to treat them as a disposable servant class. I argue that meaningful change should begin with citizenship policy. Drawing up an explicit rather than implicit policy would be a good start; one that is inclusive, which regards and treats migrants as future citizens and treats them and existing citizens with respect and fairness. This means recognising the existence of the unauthorised population, offering an amnesty and proper routes to regularisation, replacing the hostile environment with a system that checks identity not immigration status, reforming family migration routes to take account of not just economic concerns but social ones too, and rationalising economic migration routes.

There is a lot more in the book than this summary, which I have taken from the introduction. But hopefully this gives you an idea of what to expect. Do take a look for yourself!

SHARE