- BY Colin Yeo

What even is United Kingdom immigration policy right now?

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Table of Contents

ToggleI follow immigration law and policy pretty closely but, I must confess, I simply do not know what UK government immigration policy is right now. We are told there is a new points based immigration system but that tells us nothing about what outcomes the government wants from the new rules. We are told immigration will be “controlled” but, again, that tells us nothing concrete about outcomes. We are told irregular arrivals by refugees are undesirable but no actual policy to prevent it has been proposed. We are told foreign criminals will be deported but numbers of enforced removals were at an historic low even before the pandemic. We are told Global Britain is open for business but the number of visas granted to overseas entrepreneurs has fallen off a cliff. The only explicit immigration policy I can think of is a negative one: ending free movement for EU citizens. What does the government want to happen instead, though?

If I had to guess, I would say that current government immigration policy seems to be “fewer but better” or, failing that, simply “fewer”. But this is not stated anywhere, and in any case it is more of an aspiration than an actual policy: a proper policy requires some sort of implementation. The only emanations from Priti Patel’s Home Office are leaks, briefings and minimum-resistance default behaviours.

Surface level immigration policy

2000 to 2010

I knew what immigration policy was from 2000 to 2010: to encourage economic migration and discourage unauthorised migration. This was the heyday of the good migrant / bad migrant duopoly. Towards the end of the period, emphasis shifted from the first of these policy intentions to the second but the two-edged policy remained essentially in place. Criteria for work permits were loosened, new economic migration visas were invented, a drive to increase the number of foreign students was launched and no restrictions were placed on workers from new EU member countries. At the same time, the number of immigration detention centres was hugely expanded, enforced removals went up — peaking at over 20,000 per year in 2004, well over twice the current levels — and the UK border was pushed abroad wherever possible, through visa requirements, airline liaison officers and security at French ports.

Consistent with the concept of good migrants and bad migrants, some attempts were made to promote the idea of integration and a new more open citizenship policy. In reality, the policy aims were undermined by the actual policies chosen: a new citizenship exam, expansion of the good character requirement and the ultimately-abandoned probationary citizenship reforms of 2009. These changes made, or would have made, British citizenship harder to acquire and more exclusive. Neither David Blunkett nor Gordon Brown, who cared deeply about these issues, ever to my knowledge answered the question of what happens to the migrants who cannot pass the toughened tests: the answer is that they end up less integrated than they would otherwise have been, not more.

If you want to read more about that era, I cover a lot of this fairly concisely in Welcome to Britain, drawing heavily on Will Somerville’s Immigration Under New Labour, Erica Consterdine’s more recent Labour’s Immigration Policy, Mary Bosworth’s Inside Immigration Detention and Don Flynn’s prescient pamphlet Tough As Old Boots. One of the things that stands out is that there was a genuine transformation in the Home Office’s approach to immigration during the period 1997 to 2003. Consterdine explores the reasons for that and concludes it was a mix of party ideology, the influence of key policy people and networks outside and within government and key personnel, in particular David Blunkett. An optimist might draw some hope from this: if revolution happened once before, it could happen again.

2010 to 2020

I knew what immigration policy was from 2010 to 2020, or at least 2019: to discourage all forms of immigration. This was the era of the net migration target, a flimsy attempt to conceal and legitimise a drive to reduce immigration. Rules were tightened across the board: for family members, students, work visas and for EU citizens. At the same time, the Immigration Rules became considerably more complex and the cost of visas skyrocketed, causing increasing numbers of previously-authorised migrants to slip into illegality. Some of them were long term residents — the Windrush generation — and attracted considerable public sympathy when their situation became known. More recent arrivals treated in exactly the same way remain invisible.

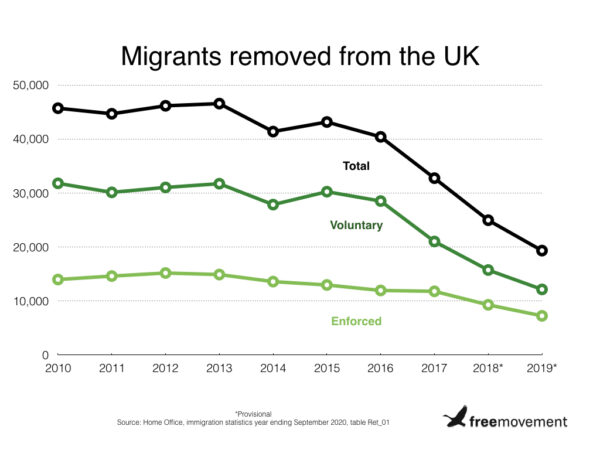

A little-known feature of this period is that the number of enforced removals fell very considerably, as did voluntary departures. This is not what the public had been led to expect and was perhaps not what some policy-makers anticipated either.

At a time when politicians claimed to want to reduce immigration, particularly unauthorised immigration, they actually increased the size of the unauthorised population. It is important to consider not just what politicians say but what they do. I will turn in a moment to the less obvious but very significant structural changes and continuities in immigration policy over the same period.

2020 to 2030?

I do not know what immigration policy is now. If I had to guess, I would say it is to reduce immigration, particularly unauthorised immigration, but perhaps to increase the “quality” of those migrants who are admitted. This could explain the scrapping of the old Entrepreneur visa and its replacement with the (much) lower-volume Innovator and Start up visas, for example. Even the “good” migrant is no longer good enough; as Trump might say, we want the best migrants.

The intention to reduce immigration is no longer explicit but the end of free movement and the decision to apply the substance of the old Immigration Rules to EU citizens from 2021 will surely have that effect. The cost of immigration application fees, the Immigration Health Surcharge, the inconvenience of obtaining and retaining a sponsor licence and the Immigration Skills Charge all look intended to nudge employers away from recruiting foreign workers.

This looks like policy making by default. What does the government actually want from immigration? Aspiring to attract the “brightest and best” from around the world is a tired platitude, not a policy. How will such people be pre-judged and attracted? Or, if the government does not want immigration at all, how is it planning to address whatever underlying reasons there might be for current levels of high migration into the UK? What is our citizenship or integration policy? Is the government going to address the issue of the unauthorised population, discussed below? Is there really going to be a meaningful review of the various hostile environment measures, as promised? I simply don’t know. And I doubt anyone at the Home Office does either.

Structural immigration policy

As I was researching and writing Welcome to Britain, I found myself standing back from the day to day grind of the immigration system. This was basically the point of the exercise as far as I was concerned. It was a chance to look at the longer term trends and less obvious aspects of immigration policy. What follows may well be astoundingly obvious in some respects. Stating the obvious can be surprisingly hard to do, though, and doing so may remind us that the current state of affairs is the outcome of policy decisions which are not necessarily permanent.

The unauthorised population

A range of government policies have had the effect of increasing the size of the unauthorised population since 2010. To my mind, this has become one of the stand-out features of the UK’s immigration system, much like it has in the United States. I found Hiroshi Motomura’s Immigration Outside the Law to be very interesting reading on this. It is a really well-written exploration of the legal conceptualisation of immigration controls in the US context, but often applicable much more widely.

An increase in the size of the unauthorised population was never announced as policy and policy-makers may have considered it undesirable. Nevertheless, it was the inevitable and predictable outcome of:

- Reducing the number of enforced removals

- Making it harder to move from unlawful to lawful status (e.g. scrapping the 14-year rule and introducing rigid human rights rules)

- Making it easier to move from lawful status to unlawful status (higher fees, more complexity, more enforcement)

- Scrapping the periodic amnesties run by the previous Labour government

It may be the case that the hostile environment was supposed to increase the number of voluntary departures. If so, this was never a stated intention in the early days, there was no evidence it would work, it was never tested and it did not work. Voluntary departures were falling even before the Windrush scandal was exposed, at which point a lot of enforcement activity was reduced.

It is all very well for politicians to fulminate about “‘illegal immigrants”, but the reality is that government policy over the last decade has increased not decreased their number. It was always obvious that this would be the outcome of those policies. It is equally obvious that the EU Settlement Scheme will increase this unauthorised population still further. This was an area of genuine structural change in immigration policy from 2010 onwards, even if it was inadvertent. There is no sign the present government intends to follow a different course or attempt to address the issue.

Secure and external border

One of the features of the contemporary British immigration system which I think is largely taken for granted but which is actually relatively new is the secure and external — or securitised and externalised, if you are an academic and prefer your words longer — border. Government policy today is simply to maintain and if possible further enhance this border, as established by previous governments.

The origins of this approach, which is now so deeply embedded it seems fanciful to imagine it could ever be otherwise, lie in the Carrier’s Liability Act 1987 and the Le Touquet Treaty negotiated by David Blunkett in 2003. It is essentially impossible now to reach the UK lawfully to claim asylum. As I write in Welcome to Britain:

Miles and miles of five-metre-high security fencing and razor wire and thousands of security staff, including riot police armed with guns, batons, body armour and dogs, now prevent migrants from climbing aboard lorries and trains bound for Britain. Security cameras are everywhere. Heat sensors are used to detect live bodies, carbon dioxide sensors detect breathing and X-rays and heartbeat monitors are also utilised.

As the controversy over small boats this summer showed, any reduction in security would be extremely unpopular in the press and a huge segment of public opinion. The Home Office announced a further tightening of security on the French coast, including “cutting edge surveillance technology”, only the other day.

The government cannot always do as it chooses, though: the French people and government might ultimately tire of UK presence and high security on French soil. On the other hand, the French may feel that permitting migrants to travel across France and gather on the French coast to cross by lorry and small boat is an even more unattractive proposition. The Le Touquet Treaty was renewed in 2018 but can be terminated by either side with six months’ notice.

Third party immigration controls

There has been a fundamental shift in the way in which immigration policy is enforced in the United Kingdom, from the border to inland. This began in earnest in 2006 with employer sanctions, was considerably expanded with the (old) points based system sponsorship system from 2008 and then from 2012 onwards was rapidly expanded through the hostile environment system of “papers, please” everyday immigration status checks by public officials and third parties and through dramatically increased enforcement. Once again, current government policy is essentially to maintain and expand a system introduced by previous governments. One suspects there is considerable institutional ideological investment by officials at the Home Office in this approach. Priti Patel has pledged to “review” the hostile environment laws but there cannot be a single person in the country who thinks she is going to scrap them.

Again, I explore this system in Welcome to Britain. One of its little-understood features is that the system does not in fact require mandatory identity checks. This leads many employers, landlords and public service gatekeepers to adopt a selective, risk-based approach to carrying out the checks: they only ask people they think might be migrants for their immigration papers. This leads to minority British citizens and long term resident migrants regularly being challenged to prove their right to live in the country while the skin colour and local accent of white British citizens acts as sufficient passport.

The system as it stands encourages racial discrimination not only against migrants but also against minority British citizens. For me, this renders the policy completely indefensible. I know many readers will not agree with this, but I do not have the same objection to a system of mandatory identity checks where any penalty is for failing to carry out the check irrespective of the immigration status of the person concerned and the system is not one solely existing for immigration enforcement purposes. There are of course other concerns that arise with such a system and it is hardly a panacea for race discrimination. But to my mind it is not a morally indefensible system and it does not involve completely abolishing right to work checks, which seems to me unlikely ever to happen.

Privatised “services”

Immigration lawyers trying to obtain one of the hen’s teeth that are free visa application appointments are all too aware that visa applications have been outsourced to private companies. This started abroad with entry clearance applications in the mid 2000s and was then rolled out for visa extension applications within the UK as well. Immigration detention centres were privatised many years ago, enforced removals are significantly privatised, with extensive use of contracted companies and staff, and even asylum interviews are now being privatised. Once again, current government policy is to maintain and expand the pre-existing approach.

Other countries do not do it this way. Earlier this year Australian scrapped plans to follow in our footsteps following widespread criticism of the British model. Sadly, the Johnson government’s apparent obsession with Australian immigration policy does not extend to visa processing.

All this is done in the name of efficiency. A privatised system may well be cheaper and simpler for the government. It is neither cheaper nor simpler for the user, though, and it isolates government officials from the people whose lives they govern. One consequence is that it encourages the drafting of Immigration Rules to allow for minimal human interaction and minimal discretion. Where civil servants are completely isolated from those whose lives they govern, the quality and the humanity of the decisions made are likely to diminish. The most extreme manifestation of this trend has been in immigration detention, where there have been repeated calls for the officials making detention decisions to meet the migrants they detain. The government has so far strenuously resisted such calls. As Mary Bosworth puts it, officials are “sequestered from the potentially destabilising effects of facing up to those they wish to remove”.

The value of migrants

For the last twenty years, migrants have been evaluated in simplistically economic terms. There is nothing wrong with registering the economic value of migrants. There certainly is a problem when economics becomes the only lens through which migrants are seen.

The idea that immigration would bring economic benefits and should therefore be selectively encouraged dates back to the early New Labour years. Arguably this did not start as a brutally utilitarian approach in which economics subsumed all other considerations. But it certainly seems to have ended that way, as Don Flynn foresaw. The Migration Advisory Committee, established back in 2007, is dominated by economists. There is nothing wrong with the economic impact of immigration being one consideration taken into account by ministers making policy. But it seems to be virtually the only consideration. The social and cultural impact of immigration laws on migrants and their families and on communities are at a fundamental level irrelevant to policy-making and have been for many years.

Once again, current government policy is simply a continuation of an approach dating back to the 2000s. Where there has been change, it is marginal: immigration is perhaps now perceived as being somewhat less economically advantageous than in previous years and there is also a view that even if it is economically advantageous it should still be restricted. Essentially, though, immigration is still assessed in economic terms, even if the policy ramifications of the impact of migration are now somewhat different.

Migration and settlement

Both David Cameron and Theresa May publicly stated that they wanted to “break the link between migration and settlement”. I don’t recall this as standing out to me as particularly objectionable at the time; it is only recently, years later, that I have come to think of this as revealing a fundamentally different — and wrong — philosophy of immigration. It can be regarded as an offshoot or logical progression from the utilitarian economic approach to immigration: migrants are useful but disposable tools without rights of their own.

The work of Hiroshi Motomura is useful here. Those who regard immigration as a purely contractual exchange may be comfortable with harsh personal consequences for a migrant who does not fulfil pre-determined rules: the migrant knows what they are signing up for, they would argue. Those who believe that rights accrue to migrants through affinity — the ties that a migrant establishes in their new community — are far less comfortable with the termination of residence and the disruption to the migrant and others that this entails.

The reality is that, aside from students and visitors, migration often becomes permanent, whatever the Immigration Rules may say. Setting harder rules for settlement than for entry, as Theresa May did as Home Secretary, does not force all non-qualifying people to leave when they come to apply for settlement. Some no doubt do, but some stay unlawfully.

From a purely practical point of view, the idea that the life outcomes for a migrant can be pre-determined by admission rules with objective “average success criteria” like education levels, language skills or previous salary is naive. Some will always fail by these standards. My own view is that it is inhumane and, quite frankly, brutal to eject those who, having moved to and built a new life in a new country in good faith, do not “perform” as required. It is also largely a fantasy. In reality, a substantial proportion of migrants who fall outside these rules stay on anyway. They were in truth already settled, but rather than continuing to live lawfully, they suffer a kind of internal deportation and live precarious, vulnerable and exploited lives outside the law.

If the restrictive policies introduced after 2010 were motivated by a philosophy or world view beyond political calculation (Cameron) and simple hostility to immigration (May) then this was it. It is the polar opposite of the approach to immigration I advocate in Welcome to Britain: to regard migrants as future citizens and treat them accordingly. It is unclear to me what view if any the Johnson government holds on this issue.

Moving on

We can see both continuity and change over the last twenty years. The period can usefully be divided into before and after the watershed of 2010 and the introduction of the net migration target. A range of policies were introduced from 2010 onwards which had the effect of increasing the size of the unauthorised population and breaking the link between migration and (lawful) settlement. There is considerable continuity in some of the fundamentals of the modern immigration system, though, and it is worth remembering that net migration did not actually fall after 2010. Immigration continued to be conceptualised in economic terms, the secure external border was maintained, third party immigration controls were expanded, further privatisation was carried out and, most fundamentally, immigration continued at historically high levels.

As Maya Goodfellow and others on the left argue, it is time to move on from this simplistic and damaging narrative that immigration is all about economic value. This is easier said than done, though. On the right of the political spectrum, even Theresa May failed to change the New Labour language presenting immigration as an economic phenomenon. Boris Johnson and Priti Patel still roll out the tired old language of the “brightest and best”. Perhaps most fundamentally, the current government is highly sceptical of the concept of rights, particularly for migrants, and is politically dependent on driving a wedge between the Labour Party and a large segment of its immigration-sceptical traditional voters.

On the left, Labour politicians have long been vulnerable to political attack on immigration policy in the context of widespread public scepticism of immigration and the need to build an electoral coalition. There have, I think, been three broad phases of policy on the left, or at least three distinctive and discernible different policy approaches. From 1945 to the death of Labour leader Hugh Gaitskell in 1963, immigration, from the Commonwealth at least, was characterised as a citizenship right and an obligation. From the Wilson years through to the New Labour era, the message was to limit immigration but welcome and protect from discrimination those who came. This was the message crafted by little-remembered Labour Home Secretary Frank Soskice, responsible for the Race Relations Act 1965, and carried forward by Roy Hattersley and others. For a short time from about 2000 to the end of Blair’s premiership in 2007, the message was that immigration enriched us all.

Neither the first of these messages nor the last proved politically successful. It can be argued that failure was down to flaws in the way the message was communicated, but it indisputable that immigration is a difficult issue for the left. It is hard now to see a way forward for progressive reform of the immigration system — or even aspects of it — which does not preserve significant parts of the status quo and rely on the falling salience of the immigration issue. Indeed, progressive policies affecting migrants are probably best expressed in a different frame to “immigration” entirely: values such as family, fairness and compassion might be used to advocate on issues such as the separation of families, the discriminatory effect of the hostile environment and the resettlement of refugees. The good news is that the importance of immigration as an issue has fallen drastically since the Brexit referendum. The bad news is that issues such as small boat crossings, the foreign criminal folk devil or a terrorist attack can bring the issue right back to the front and centre of the public’s mind.

SHARE