- BY Nick Nason

Is the hostile environment working?

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

In a review of Amelia Gentleman’s book The Windrush Betrayal, David Goodhart of the Policy Exchange think tank said this:

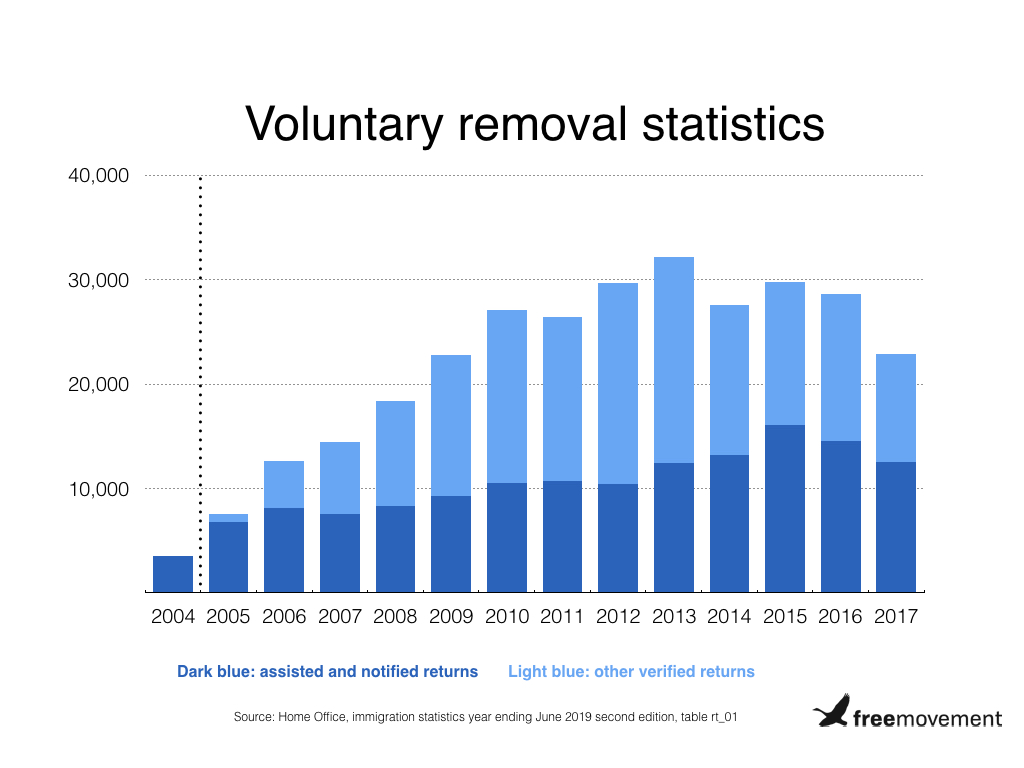

Over … [the] period [2004-2018] the number of voluntary removals rose sharply from 3,566 in 2004 to 28,655 in 2016, perhaps some evidence that, despite Gentleman’s assertions, the hostile environment was working and was prompting people to leave voluntarily. At least until the Windrush scandal itself threw a spanner in the works—voluntary removals last year fell to just over 13,000.

Mr Goodhart had made the same claim in a paper that he co-authored in 2018:

the number of voluntary removals has increased from 3,566 in 2004 to 28,655 in 2016 (though falling to just over 18,000 in 2017)—an increase of over 700 per cent which may be evidence of the “hostile environment” working.

Can statistics on voluntary removals be used to support this hypothesis?

Defining the hostile environment

Broadly, the hostile environment refers to a set of government rules the aim of which is to make it so difficult for irregular migrants to live in the UK that they choose to return home themselves.

Since Windrush, there has been an argument about the genesis of this policy. In the wake of the scandal, the Conservative government pointed to use of the phrase by Liam Byrne, then a Labour frontbencher, in 2007.

Mr Goodhart argues that “the phrase and some greater rigour in status checking stems from the mid 2000s… but then was beefed up (at least in theory) in stages from 2010”. In other words, it makes sense to look at the trend in voluntary removals from the mid-2000s to get a sense of whether the hostile environment is successfully encouraging migrants to “self-deport”.

You choose a pretty arbitrary date for the start of the hostile environment, the phrase and some greater rigour in status checking stems from the mid 2000s I think but then was beefed up (at least in theory) in stages from 2010

— David Goodhart (@David_Goodhart) January 7, 2020

As Colin writes in his extended piece on the subject, for most lawyers the hostile environment began in earnest with the Immigration Act 2014 following Theresa May’s well publicised interview in the Telegraph in 2012.

The provenance and precise composition of the hostile environment are interesting and important questions. But for present purposes, let us adopt Mr Goodhart’s definition, and agree that the hostile environment mainly consisted of increased use of employer sanctions for illegal working from the mid-2000s onward.

His point is that voluntary departures have also increased significantly since then, which may be evidence that the hostile environment was working — at least until Windrush, which “threw a spanner in the works”.

Voluntary removals from the UK

Home Office statistics on migrants being removed from the UK distinguish between “enforced” and “voluntary” removals. In turn, the overall voluntary removals number comprises the following categories:

‘Assisted returns’: individuals liable to removal from the UK who wish to leave voluntarily make an application to the Voluntary Returns Service and who are accepted to receive a re-integration package as part of their departure or those who are assisted in their return by having the flights arranged at Home Office Expense.

‘Controlled returns’: where a person liable to removal from the UK leaves voluntarily at their own expense but who notifies the relevant authorities prior to departure and/or where those authorities oversee their departure.

‘Other verified returns’: relate to Immigration offenders (liable to removal from the UK) or subject to immigration control (not yet notified of liability to removal) for who it has been established have left or have been identified leaving the UK without formally informing the immigration authorities of their departure.

The notes to the statistics explain that ‘Other verified returns’ can be identified either at embarkation controls or by a variety of data-matching initiatives. The other verified returns figure constitutes the bulk of total voluntary removals: over 50% in most years 2010-2019, and in some years almost 70%.

Changes to the calculation of voluntary returns

Mr Goodhart says that total voluntary removals increased by 700% between 2004 and 2016. But that is largely because ‘Other verified returns’ was not included in the total until January 2005.

The other verified returns number also rose very sharply from the time the Home Office began including them. It increased by 45% between 2007 and 2008, for example. The Home Office itself says that

The steep rise in other voluntary departures [in 2007-2008] could be accounted for by the reintroduction of limited embarkation duties (monitoring of departures) at major airports for specific flights and better data matching provided by e-borders.

The Migration Observatory at Oxford University, in a 2015 briefing cited by Mr Goodhart’s Policy Exchange paper comments that:

The number of recorded “voluntary” departures has increased, although it is not clear to what extent data improvements are responsible for the change… comparisons over time must be treated with caution because improvements in collecting data on voluntary departures since 2005 may have contributed to higher numbers.

In other words, it is quite possible that much of the 700% increase from 2004 to 2016 is a result of better data rather than more voluntary departures.

Bearing all this in mind, it is very difficult to see how the increase in the voluntary removals statistics from 2004 to 2016 can be used to support any position, let alone the one argued for by Mr Goodhart. The Migration Observatory concludes in its latest briefing on the subject that the data problems make it “difficult to evaluate the impact of the hostile environment using voluntary returns data alone”.

And the Windrush “spanner in the works”?

Mr Goodhart further seems to suggest that the number of voluntary departures has decreased from its 2016 peak as a result of the Windrush scandal.

This is a puzzling theory, not least because the largest drop (from 29,000 in 2016 to 23,000 in 2017, using Mr Goodhart’s own figures) occurred before the Windrush scandal came to public attention. Looked at another way, the quarterly total for overall voluntary returns fell by 33% between Q1 2016 and Q1 2018. The Windrush scandal blew up in April 2018.

It is true that the figures for 2018 are lower still, at just 18,000. But there is no evidence that this is related to the fallout from the Windrush scandal, and appears to be the continuation of a pre-existing trend.

The evaluative black hole

Mr Goodhart’s underlying argument is that there is nothing inherently wrong with an internal border, or indeed a hostile approach to irregular immigration. He is, of course, entitled to this view.

We would simply say that reliance on voluntary return statistics does nothing to support it, or suggest (at all) that the hostile environment is “working”.

The fact that Mr Goodhart is having to rely on such shaky statistical foundations is symptomatic of the complete absence of evaluative tools available to the Home Office to monitor the effects of its policies, and particularly in respect of the hostile environment.

Either way, Mr Goodhart should be commended for engaging and responding constructively to our criticisms made above via Twitter.

SHARE