- BY CJ McKinney

Briefing: the Tier 1 (Investor) route

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

The Tier 1 (Investor) visa allows foreign citizens to get permission to live in the UK in return for an investment of £2 million in the British economy. The investment can be in shares or bonds issued by UK companies. Around 12,000 people have come to the UK on a Tier 1 (Investor) visa since the route was launched in 2008, of which most — 7,500 — were dependent family members.

The £2 million puts the investor on the road to settlement in the UK after five years. Accelerated settlement can be had by upping the investment amount: £5m gets settlement after three years, and £10m settlement after just two.

Clients

“Our clients are typically families looking to relocate to the UK as they want to educate their children here”, says James Perrott, head of immigration at Macfarlanes. “We also see applications from individuals in their late teens / early twenties who are looking to study and then subsequently work in the UK. In this situation, their parents will provide the funds for them to submit a Tier 1 (Investor) application”.

With a £2 million minimum buy-in, those families will be among the world’s wealthiest. But it doesn’t necessarily cost them much money in the long run, since the investment amount is not a fee or cash payment to the government. The investor just exchanges their money for a stake in or loan to a British company, which may well increase in value. A Migration Advisory Committee review of the route in 2014 found that “the direct investment itself is not of great benefit to the UK. Rather, the benefits of the route appear to lie in the indirect consumption by the investor, and associated taxation, predominantly value added tax”. In other words, making it easy for wealthy foreigners to spend time in the UK is good for the economy because of the money they spend.

Not all will make their home here forever. “The other thing they’re after is freedom to visit without needing a visa”, says Sophie Barrett-Brown of Laura Devine Solicitors. “Ultra high net worths snap up passports around the world”. Nichola Carter of Carter Thomas agrees: “A lot of people just see it as a super-visitor visa”. For the really super-rich, tying up a small part of their fortune for a few years is worth it to be able to come and go as they please. Some do progress to citizenship, but “not as often as you’d expect”, Carter says.

Even if British citizenship is the ultimate goal for some, it’s no “cash for passports” scheme. While investors, unlike most economic migrants, do not initially have to pass an English language test, they do have to pass one when they come to apply for settlement, as well as having spent a minimum amount of time in the UK each year. And unless married to a British citizen, qualifying for citizenship still requires five years’ residence — accelerated settlement provides no shortcut.

Money

Investment visa schemes have been criticised as a possible vehicle for money laundering. These concerns escalated in the years following 2008, when the old Investor Immigrant programme was replaced with Tier 1 (Investor) as part of the new Points Based System.

“The pre-PBS version of Investor was actually very rigorous”, Barrett-Brown recalls. “I remember the lengths we’d have to go to in order to demonstrate the provenance of the funds. Then Tier 1 comes in and it’s, oh, you’ve got some cash in the bank for three months. The initial form of Tier 1 (Investor), one might argue, was something of a watering down of the rigour in the consideration of where the money is coming from”.

No greater rigour was forthcoming for some time. The Migration Advisory Committee’s 2014 review found that “the Tier 1 (Investor) route has been largely unchanged since it was introduced”. A report by Transparency International said that there had been “relatively open opportunities to launder wealth through the UK Tier 1 Investor scheme during the period from June 2008 to April 2015 in particular”.

April 2015 was when the government clamped down by requiring investors to open a UK bank account before applying for their visa, triggering anti money laundering checks by the bank. It had previously been possible to get the visa first, and then use it to assuage the bank’s due diligence concerns. Barrett-Brown says that “in the past it might have suffered a little bit of unconscious abdication of responsibility, with the Home Office assuming that the banks would do the due diligence and the banks assuming that if the person has a visa granted by the Home Office they must have been checked out”.

Since then, criminal records checks have been introduced, and applicants must also prove the source of the money they propose to invest unless they have had it for at least two years.

Trends

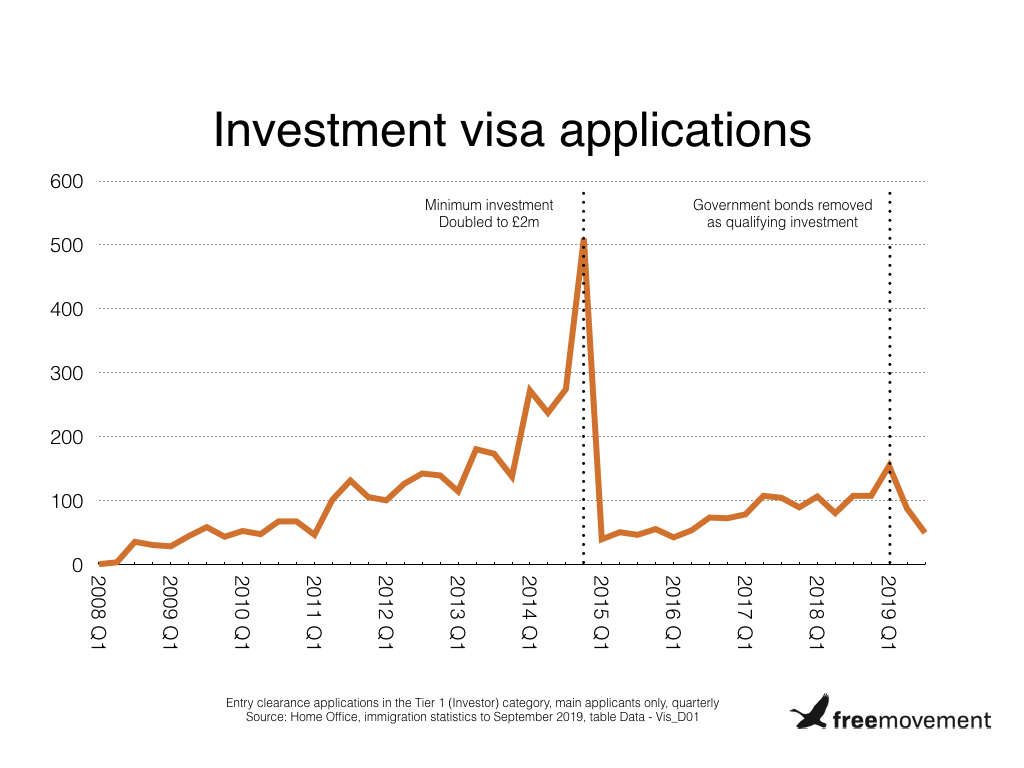

Investment visa applications spiked in the final quarter of 2014, and then fell dramatically. Practitioners put this down to the doubling of the minimum investment required, from £1m to £2m, in November 2014. Barrett-Brown thinks that only a “small proportion” were motivated by the need to apply ahead of the tighter regulation that was introduced not long afterwards.

A similar pattern, on a smaller scale, can be seen in early 2019 following the removal of UK government bonds as a qualifying investment. “My hunch”, Perrott says, “is that the drop in numbers in the third quarter was due to people bringing forward the submission of their applications to the first quarter, so that they were submitted before the rules changed”.

These previous changes were flagged well in advance, allowing investors to bring forward their applications to avoid being caught by new rules. The desire to stop investors changing their behaviour like this may have been at the root of last year’s suspension fiasco, when the Home Office announced that the Tier 1 (Investor) route would be suspended immediately — only to reverse course a few days later.

“Trying to close a route without any warning, when there are applications in the pipeline, was unprecedented”, Carter points out. Although the number of people affected was small, the whole point of the UK as a place for high net worth investors to park their money and their family is its relative stability and respect for the rule of law. Trying to close down a live visa route overnight does nothing for that reputation.

October 1994: Immigrant Investor scheme launched, with a minimum threshold of £1 million.

June 2008: Tier 1 (Investor) introduced.

February 2014: Migration Advisory Committee review finds limited economic benefit to Tier 1 (Investor) and makes various recommendations for adjustments.

November 2014: minimum investment raised to £2 million; caseworkers are empowered to refuse applications if there are reasonable grounds to suspect that the money was obtained unlawfully.

April 2015: investors required to open UK bank account, with associated money laundering checks, before applying.

March 2019: government bonds removed as qualifying investment.

While the tightened rules on investment visas may not have been a major deterrent overall, they may have put off some nationalities more than others. “It used to be high net worth Russian individuals, going back five plus years ago”, says Nichola Carter. Home Office statistics show that 23% of all Tier 1 (Investor) visas went to Russian citizens between 2008 and 2015. Between 2015 and 2019, that fell to 14%. Investors from East Asia — China, Hong Kong and Japan — accounted for 40% in the later period, with Middle Eastern investors up to 9%.

Tips

Perrott thinks that Tier 1 (Investor) is “generally easy to explain to clients”. But the devil, as ever with the UK immigration system, is in the detail.

“The Home Office keeps making minor amendments to the investment requirements and the documentation required to evidence that these requirements are met”, says Perrott, who sits on the economic migration sub-committee of the Immigration Law Practitioners’ Association. “It is difficult for clients and financial advisers to keep track of these changes which can cause problems, especially as they can be applied retrospectively”.

It’s also worth making sure that the wealth manager who will advise on what shares or bonds to buy is aware of how the financial decisions interact with the visa rules. Perrott says that “the reinvestment requirements are becoming more complex and we have seen a number of situations where clients and their financial advisers have made mistakes which have led to non-compliance with the requirements”. His top tip is to get a wealth manager who is “knowledgeable and experienced in operating these types of portfolios”. Carter adds that recommending a wealth manager to clients can be a tricky business given the sums of money involved. “We have a number of advisers that we will recommend, but ultimately we’ll leave that final decision down to the client”.

Specialist knowledge also comes in handy when warning clients about potential pitfalls down the line. Barrett-Brown points to the fact that passing an English language test kicks in at the settlement stage, despite not being a requirement for the initial visa. “I’ve seen cases where some overzealous adviser has put the applicant on a path to two-year ILR without telling them that they’ve got to teach themselves English in that two-year period”, she says.

“Often you find that people just haven’t integrated”, Carter notes. “Their kids often speak perfect English by the time they’ve done five years at private school, but mum and dad can quite often still be really struggling with their English”. Similarly, the settlement requirement of not being absent from the UK for more than 180 days in any 12-month period can trip up the poorly advised. Carter says that she often takes on clients “who come to me in year three, four or five and they just haven’t done what’s needed to get indefinite leave to remain. Either they’ve not improved their English or they’ve been absent for too long, and they have to start the whole clock ticking again”.

Another trick of the trade involves the two-year rule on the investment funds. Many clients think that the money needs to be resting in their account for two years, which is not the case so long as the source of more recently obtained money can be demonstrated. One of the permitted sources is deed of gift — “which frankly isn’t really showing the source of the money”, Barrett-Brown points out, “but it’s permitted. So the money can be gifted, commonly from a family member or even a partner — one spouse may gift the money to another spouse, and that is the source of the funds in Immigration Rules terms. It’s something of a nonsense that the Rules permit that, but they do”.

Carter cautions that “it has to be an irrevocable gift. Once you explain to somebody who thinks they can gift the money for Home Office purposes that it actually has to be legally binding, there’s usually at least a pause in their thinking”. Selling property can be another way to avoid having the money sitting idle for two years: even if sold recently, the sale will constitute a valid source of funds for Tier 1 (Investor) purposes.

But immigration law hacks will only get you so far. Everyone spoken to for this article emphasises the importance of making sure you know what the client’s objectives are in order to give the best advice. “Investment clients have a tendency to come to you and say that they want to be an investor because that’s what their friends have done, but it’s not necessarily the right route for them”, Barrett-Brown says. “It’s important to really understand why they want the immigration permission — there may be a better route”.

Forecasts

You might think that Brexit would have a negative impact on demand for investment visas. After all, the British passport it eventually offers will no longer come with the right of free movement in the European Union.

But Barrett-Brown says that’s the wrong way of looking at it. In fact, free movement no longer covering the UK could see more people applying for an investment visa here rather than fewer. That’s because many currently use the very liberal citizenship-by-investment rules of other European countries as a back door to the UK — something that won’t be possible in future.

“A lot of high net worth individuals would consider going for a European passport in order to be in the UK”, the Laura Devine partner explains. “They’d get a Maltese or a Cypriot passport, where you can directly apply for citizenship and there isn’t a meaningful residence period, and with that they come and live in London. Their objective all along was to live in London, not to live in Cyprus”. In future, rich non-Europeans may end up applying for a UK investment visa as well as a European one — becoming what Barrett-Brown calls a “dual-solution” investor.

Perrott also thinks that demand is likely to rise, if only because wealthy Europeans will no longer be able to rely on free movement for easy access to the UK. “As EEA nationals will have to obtain immigration permission to enter the UK post-Brexit”, he says, “some of them will apply under the Tier 1 (Investor) route so numbers will inevitably increase”.

Brexit aside, the closure of the Entrepreneur route has had a displacement effect, with Barrett-Brown “having to advise some clients who would have been much better suited to Tier 1 (Entrepreneur) to consider Investor”.

On the side of the ledger, any further tinkering with the route could yet suppress demand, at least in the short term. “I understand that the Home Office is still considering introducing a wealth audit requirement”, Perrott says. “From the limited amount of information available, it appears that this will involve the applicant being required to provide in support of their application a report from an independent, regulated auditor confirming the source of the individual’s wealth”. It remains to be seen whether the government’s desire to appear “open for business” in a post-Brexit world will trump demands for increased scrutiny of foreign investors.