- BY Colin Yeo

It is time to think about rejoining the EU’s Dublin asylum system

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Table of Contents

ToggleThe “Dublin system” is the process within the European Union for allocating which country is responsible for deciding asylum applications. Its purpose is, essentially, to force refugees back to their point of entry into the EU, usually Greece, Hungary or Italy. The system began as the Dublin Convention in 1995 but was later incorporated into EU law. Indeed, the Dublin system was arguably one of the drivers of the whole Common European Asylum System.

The United Kingdom decided to leave the Dublin system at the end of 2020 as part of Brexit. With that decision, the UK lost the ability to return asylum seekers to EU countries. Those arriving in small boats or by other means must now have their asylum applications decided in the UK and cannot be transferred back to an EU country to have their claim assessed there. Who knows whether the possibility of removal back to the EU would dissuade someone from paying a lot of money to get into a dinghy on a French beach at night, but asylum applications have now started to rise quite dramatically.

The UK’s departure from the Dublin system was a choice: it may have been possible to remain a participating country from outside the EU. Non-EU members Switzerland and Norway both participate in Dublin, for example. Those countries are closely aligned with the EU in general, though. The UK government decided that a more distant relationship was necessary and therefore withdrew.

The Dublin system is generally unpopular with refugees, refugee rights campaigners and refugee lawyers. Refugees are often very badly treated in the countries that they arrive in and pass through. In the 2011 case of MSS v Belgium and Greece (application no. 30696/09) the European Court of Human Rights held that conditions were so poor in Greece for asylum seekers that they amounted to inhuman and degrading treatment. In the same year, in joined cases C-411/10 and C-493/10 NS v United Kingdom and ME v Ireland, the Court of Justice of the European Union effectively suspended Dublin transfers from participating countries back to Greece.

Over the years I have acted on behalf of quite a few refugees resisting removal via the Dublin system. Some had had appalling, traumatising experiences within the European Union. They really did not want to be sent back, having gone through huge risks and spent vast sums to get to the UK.

The UK was a net recipient of refugees under Dublin in recent years

I was quite surprised, then, when in the run-up to Brexit I saw notable refugee rights campaign groups concerned that the UK was leaving the Dublin system with no replacement on the cards. I knew that small numbers of children and family members had been relocated to the UK but I assumed that the transfers into the UK were outweighed by transfers out of the UK. I thought the Dublin system thus did more harm than good to refugee rights, on balance.

In reality, transfers into the UK exceeded transfers out of the UK for several years in the run-up to Brexit. In other words, the UK was a net recipient of refugees under the Dublin system. This seems counterintuitive to those familiar with why the system was introduced in the first place — very much at the behest of the UK — and how the system is supposed to work.

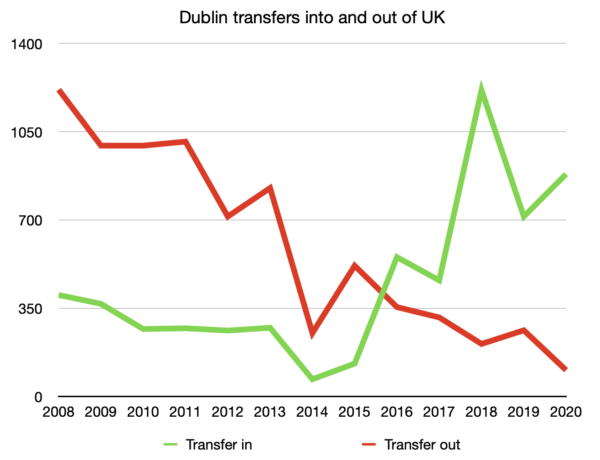

This simple chart shows the data from 2008 to 2020:

As you can see, the number of transfers out declined over time and the numbers of transfers in increased. In 2016 the UK became a net recipient.

Refugee rights are not a simple numerical question. The transfers-in were generally children being reunited with family members who would have no safe and legal route to reaching the UK. The transfers-out would usually be adults being transferred to Greece, Hungary or Italy. These were countries they had passed through on their way to the UK and in which they would face sometimes grim conditions and perfunctory asylum determination procedures. Sometimes their asylum claims would already have been allowed or refused in those countries and sometimes they would have decided to move on before finding out.

The UK transferred out fewer people under Dublin than similar countries

Those familiar with the Dublin system might have expected transfers out to decline sharply after the MSS and NS rulings in 2011 and perhaps after the Syrian refugee crisis began in 2014-2015, under the strain of which the Dublin system was reported to have broken down. But it was surprising to me, at any rate, to see a sustained fall over the whole period 2008 to 2020. Transfers-out and transfers-in might both have been expected to increase following the coming into force of the third iteration of the Dublin arrangement in 2013. The increase in transfers-in from 2015 was perhaps more predictable, although it nevertheless surprised me.

This raises the question of what was happening in other countries participating in the Dublin system. That data is available via Eurostat, the EU statistics agency. Peter Walsh at the Migration Observatory has put together a neat tool you can use to explore some of the trends (although watch out for the variable x-axis).

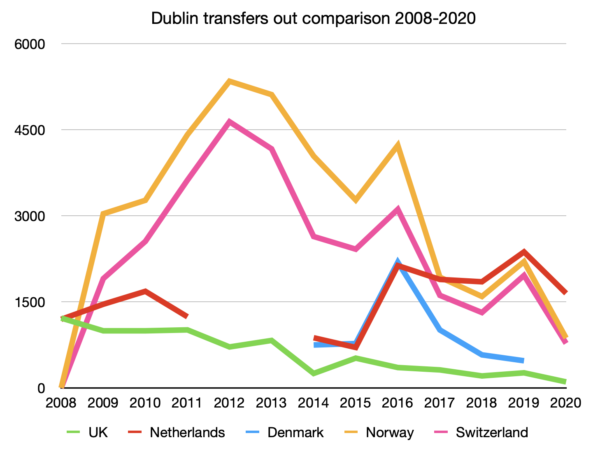

To make things simple, I’ve picked out some comparator countries and used a fixed scale below. Denmark, the Netherlands, Norway and Switzerland are, like the UK, non-arrival countries mainly on the northern and western periphery. Additionally, I thought it would be interesting to include Norway and Switzerland because they are not members of the EU.

There are missing data for some years but it can be seen that the UK was consistently transferring out considerably fewer refugees under Dublin than at least some other participating countries. Those noting that the UK graph line is differently shaped to the first chart will also note that the x-axis scale has changed to accommodate the far higher numbers from other countries.

I am not sure whether it is really relevant here, but all the comparison countries received considerably fewer asylum seekers than the UK during that period. The UK had more asylum seekers to choose from, so to speak.

Peter has also put together an overall comparison of the UK against other participating countries over the whole period of 2008 to 2020:

Overall, the UK did transfer out more people than it received under Dublin. But only just.

Apparently high ratio of requests to actual transfers

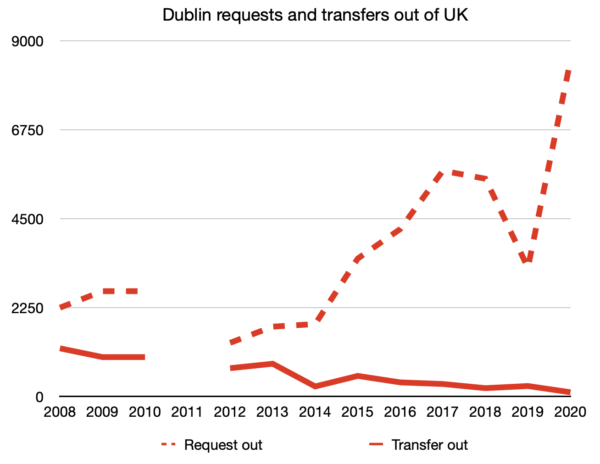

The Eurostat data also reveals how many requests for transfer different countries made. I thought this would be interesting as a way of looking at the “success rate” of requests for transfers out. It might partially explain the low number of transfers-out from the UK if the UK had a particularly low success rate when making requests (although this would then generate further questions, to be fair).

There is certainly a substantial gap between the number of transfers the UK requested and the number of actual transfers effected:

The UK did not perform very well on this metric compared to other countries. Over the whole period 2008 to 2020, the UK’s percentage of successful transfers compared to requests was 16%, compared to 27% for Denmark, 27% for the Netherlands, 29% for Norway and 29% for Switzerland. But the absurdly high number of transfer-out requests the UK made unsuccessfully in 2020 might have skewed those figures a little.

What conclusions can we draw?

The political purpose of the Dublin system was, from the UK government’s perspective, to enable transfer of asylum seekers to other countries around Europe. The UK clearly envisaged that it would be a net “exporter” of asylum seekers. Since 2016, that has not proven to be the case.

Yet other countries participating in Dublin in northern and western Europe, away from the entry points of Greece, Hungary and Italy, have in absolute terms transferred out far more refugees than the UK. They have also transferred out far more refugees than were transferred in. The UK would appear to have been singularly ineffective in transferring out refugees during its participation in the Dublin system.

I do not know why that is. It might be related to poor management at the Home Office. The Third Country Unit responsible for Dublin transfers was reported to be singularly dysfunctional. It might be related to better access to justice in the UK than other countries, meaning that refugees were better able to challenge their transfer elsewhere. There might be other explanations.

An important point to take away, though, is that the Dublin system offered a safe and legal route for some particularly vulnerable refugees to reach the UK to be reunited with family members. When the UK left the Dublin system, that safe and legal route was lost. There is no viable legal route by which more than a tiny handful of refugees in Greece, Italy, France or elsewhere can be admitted to the UK. There has been a lot of campaigning and advocacy work done on this but, so far, the present government seems to be unwilling to countenance lawful entry to the UK from within the EU.

Can the UK rejoin the Dublin system?

The Dublin system is part of European Union law but that does not prevent the active participation of some non-EU countries, including Norway and Switzerland. The legal deals enabling their participation do not seem to require direct oversight by the Court of Justice of the European Union, which has been a red line for successive UK governments.

In the run-up to Brexit, the UK did propose a replacement for the Dublin system, as discussed in some detail in this House of Commons Library briefing. The proposals seem to have represented a very one-sided arrangement in which receiving countries in the EU would be bound by mandatory requirements but the UK would only admit vulnerable refugees at its own discretion. This was reportedly and understandably described in Brussels as “very unbalanced” and “not good enough”.

No effort therefore seems to have been made by the UK to remain part of Dublin as it already exists. A year of failing to reach alternative returns arrangements and a look at the data on the performance of other participating countries should perhaps prompt some re-evaluation.

Should the UK rejoin the Dublin system?

Many refugee rights advocates will be aghast at this question, the obvious answer to which would be thought to be a resounding “no”. But…

Firstly, the Dublin system offers a safe and legal route for refugees within the European Union to reach the UK. It seems to me unrealistic to hope that the present government would create such a route unilaterally, although it is certainly within its power. For all the talk of “safe and legal routes” by the Home Office, I think we all know that is just talk.

There is a trade-off, from a refugee rights perspective. But that perhaps makes the idea politically viable. The trade-off is that some refugees will be removed to the EU.

In the years running up to Brexit the number of actual transfers-out was very low. But the Home Office might put its house in order — which is possible if we look at the relative performance of other Dublin participant countries — and numbers of transfers-out might increase. The sharp and dramatic increase in requests to transfer-out in 2020 suggests that more such requests could have been made in previous years. As things stood, almost all those requests were utterly pointless because the pandemic made removals impossible in the short term and the UK decided to leave the Dublin system at the end of 2020 anyway, meaning the transfers then became impossible.

A potential increase in transfers-out might actually be an advantage from a public policy perspective. The dramatic increase in small boat crossings is a serious issue, albeit one that must be kept in perspective. Small boat crossings are dangerous and lives have been lost. Grimly, we do not know how many have died because the bodies are sometimes lost. Small boat crossings seem inherently more risky than by lorry and a full-on disaster always seemed inevitable.

Entry by lorry was far from free of risk and around 300 people are known to have died seeking to enter the UK since 1999. Still, small boat crossings aggravate the media and the public in a way that entry by lorry did not. The present government will make life harder and harder for refugees as a consequence, although with little prospect of this having the desired effect of deterring anyone from coming. A lot of refugees will be immiserated as a consequence.

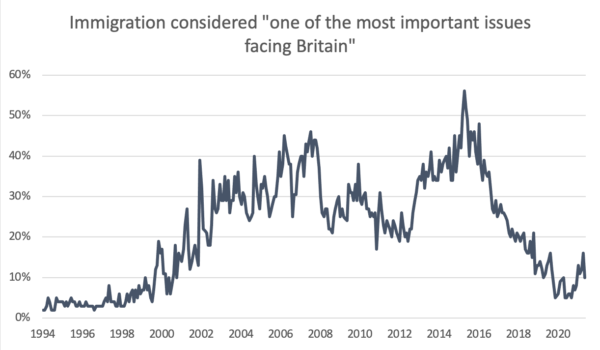

That said, public anxiety appears to remain relatively low despite all the frenzied media coverage. But the emergence of more apolitical issues such as the pandemic and global warming which do not so clearly drive voting behaviour might hide the salience of immigration.

Rejoining the Dublin system offers both a safe and legal way for some vulnerable refugees to reach the UK from within the EU and a way to remove those arriving by small boats and by other means back to EU countries. It may or may not deter arrivals but it does offer a response.

There are also safety mechanisms belatedly built into the Dublin system. Transfers-out can be challenged for those who are particularly vulnerable or where an asylum system has arguably broken down, as happened with Italy. A potential transfer within the Common European Asylum System, with its various safeguards, to Greece or Italy is not the same as a transfer to a third country somewhere outside the jurisdiction of the Court of Justice of the European Union and the European Court of Human Rights. I have publicly stated my scepticism that a third country will be found willing to accept refugees transferred from the UK, but I might be proved wrong about that and the government continues to press for it.

There are other less tangible but perhaps important advantages to rejoining Dublin. It might operate to bind the UK into certain minimum standards and procedures, for example potentially making off-shore processing of asylum claims impossible. Denmark is attempting to explore this possibility from within the EU and the Dublin system but may (hopefully) find it is impossible. It also shows some solidarity with EU countries who receive and decide far more asylum claims than the UK and offers a way to cool the ongoing dispute with France. As neighbouring countries both participating, at least to some extent, in a common European asylum system, the possibility of co-operation, joint patrols and so on is surely greater.

I suspect there are two reasons the present UK government is unwilling to countenance rejoining Dublin. Firstly, it sounds European and involves multilateral cooperation with the EU rather than bilateral cooperation with individual states. This makes it highly unpalatable to a certain breed of Brexiteer. But as we have seen, non-EU Norway and Switzerland are both Dublin system participants. They are not associated with the whole of the Common European Asylum System: just Dublin and the underpinning Eurodac database. Their involvement is not subject to direct Court of Justice of the European Union oversight.

Secondly, the UK was ineffective at achieving transfers-out. As we have seen, the UK was a net recipient of refugees from 2016 to 2020. However, as the comparison with other participating countries and the sharp increase in transfer requests in 2020 despite a fall in asylum arrivals shows, this was not necessarily inevitable.

Maybe it is time for us all to think again about the Dublin system. It represents both an oven-ready returns deal with the EU and a safe and legal route for vulnerable refugee children.

SHARE

One Response

So informative Collin many thanks. I think as long as the ECJ remains the other elephant in the room for the UK.