- BY Sonia Lenegan

Independent Chief Inspector’s report on deprivation of citizenship shows a high number of stalled cases

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

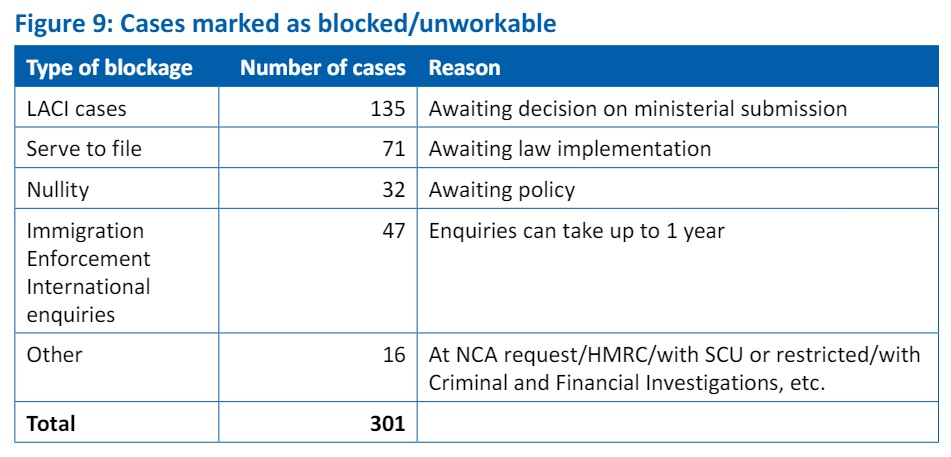

The Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration’s report ‘An inspection of the use of deprivation of Citizenship by the Status Review Unit’ contains some interesting points around the high number of Albanian decisions, proposed solutions for what happens to a person after deprivation and some fairly troubling use of spreadsheets. Also, at the time of the inspection, there were over 300 cases that could not be progressed for various reasons. Most of those were (and still are) awaiting a decision by the Home Secretary on a ministerial submission.

For anyone needing a refresher, Colin has written an explainer on the rise in the use of deprivation and the different types of decisions that can be made.

Background

The report explains that the Status Review Unit deals with most deprivation cases (around 650 cases a year) and where the main factor for consideration of deprivation is fraud or serious organised crime. There is a separate, Special Cases Unit, which manages a smaller number of deprivation cases that involve national security interest issues, this was out of scope for this report.

Between 1 January 2019 and 10 May 2023 there were 2,817 referrals to the Status Review Unit made on fraud grounds. 2,350 were accepted for consideration and 467 were rejected. The main source of the fraud referrals is the Passport Office (para 5.23).

High numbers of referrals of Albanian or Iraqi nationals

Apparently there were two specific operations that had generated most of the referrals, these targeted Iraqi and Albanian nationals who had used false identities (including false nationalities) on arrival to the UK (para 5.30). The main way the fraud came to light was when applications (passport, visa) were made for family members, including children.

The National Crime Agency estimated around 90% of cases they referred for deprivation were Albanians and this was mainly due to the ability of the Home Office to access local records in Albania to confirm details of identity and nationality (para 5.32). The inspector notes concerns have been raised about the possibility that Albanians are being discriminated against and included a reference to this article of Colin’s from last year.

Home Office staff gave some fairly bizarre responses when asked about potential discrimination, saying that they had no control over the cases that are sent to them and that Albanian cases being successfully progressed is why similar referrals are then made. The report makes the point that “inspectors were not aware of any ministerial authorisation or legislation that permitted direct discrimination on the grounds of race” (para 5.36).

Data errors

The inspector noted “significant discrepancies” between data held by the Performance Reporting and Analysis Unit which reported 616 fraud cases waiting for a decision as opposed to the Deprivation Team’s records which said this figure was 1,084 (para 1.7). This may be because of the variety of multiple caseworking systems being used, which included record keeping on local spreadsheets.

Data kept in spreadsheets also contained other errors and variations, for example Jamaica was recorded as “JAM, Jamaica and Jamica” (para 5.19). The “work in progress” spreadsheets had 77 cases recorded as “the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia” (para 5.48).

Decision making and delays

Decision making is reported as being in a good state, with “detailed, good-quality decision notices” being produced (para 1.9).

The target for decision making is 1.1 decisions per caseworker per week. Approximately 240 cases were on hold awaiting a policy or ministerial decision or “updates to IT systems” (para 1.11).

More than two thirds of the deprivation decisions made on fraud grounds between 2012 and 2022 were made in the last two years, with 263 decisions in 2021 and 308 in 2022. The increase is explained as possibly being due to improved resourcing and caseworking, as well as the inclusion of family members (3.23)

Significant delays were found in some cases, including the case study at page 35 which showed a seven year delay between the referral and the deprivation decision. The ten oldest cases ranged from 18 November 2002 to 28 July 2008, the reasons for the delay with these cases apparently include waiting for the outcome of an ongoing prosecution or waiting on action by colleagues in international teams (para 5.60).

New processes awaiting ministerial sign off

A Home Office manager told inspectors that they were “seeing a “trend” of human rights and limbo arguments being used in appeals and that they were “looking to see what we can do about it or argue against it” (para 6.22). The “limbo” argument relates to the period between a person losing their citizenship and any grant of leave to remain being made.

Following the Court of Appeal’s decision in Laci v Secretary of State for the Home Department[2021] EWCA Civ 769 this risk was considered to be higher in cases where there was a delay between notification of deprivation being considered and the decision actually being made. As a result, 135 cases were waiting for a decision on a ministerial submission in relation to the Laci judgment (paras 5.61 and 6.24).

The recommended option is that when a deprivation order is made, leave to remain for one month will automatically be issued and then the person can apply for further leave to remain during that period (para 6.25). Alternatively, it was proposed that article 8 should be considered at the time the deprivation decision is made. This would mean that where notice of deprivation is given, an indication would be provided as to whether the intention is ultimately to remove the person from the UK or to grant them limited leave to remain (6.26).

The Home Secretary has not made a decision on how to proceed.

Hundreds of cases not progressing

Deprivation decisions being made without notice is a recent power, introduced to section 40 (5A) of the British Nationality Act 1981 by the Nationality and Borders Act 2022 on 10 May 2023. At the time of the inspection, there were 71 cases awaiting the implementation of the legislation. Some of those are likely to have moved since then but it seems the Home Office intended to stagger them.

In total there were over 300 cases with barriers to progression:

Quality assurance

The quality assurance process seems fairly robust compared to other areas of the Home Office. Where a quality assurance check identifies at least one significant error the decision maker has to meet with their line manager and the senior caseworker so that feedback and learning points can be discussed (para 7.10). Senior caseworkers carry out a minimum of two quality assessments per decision maker each quarter. The Deputy Chief Caseworker will then carry out quality assessments on those cases to ensure that they agree with the senior caseworker’s assessment.

Once a decision to deprive is made, the case is added to a spreadsheet and monitored to see whether or not an appeal is lodged and what the outcome is. Where the appeal is unsuccessful the deprivation order will be served and the person contacted for evidence as to whether they should be granted leave to remain on article 8 grounds.

At the time of the inspection there were 450 cases on this spreadsheet (para 7.22) and “where possible the team aimed to check the first 50 on the spreadsheet each week”. Unsurprisingly, this system leads to lawyers writing to the Home Office asking for the case to be progressed post-appeal, but the team then needs to check with the appeals unit before they can consider granting leave (para 7.26). In the majority of deprivation cases, a grant of leave to remain is made (para 7.30).

Of 296 deprivation appeals that were heard in 2022, almost 25% were allowed (para 7.32). The deprivation team has a role that is dedicated to liaising with the appeals team and also monitoring appeal outcomes to identify trends and learn lessons. Most of their focus is on fraud deprivations (para 7.31). Decision makers reported finding the information circulated on appeals useful and that when it comes to identifying policy or training gaps “most feedback comes from appeals”.

Home Office staff were reportedly frustrated that immigration judges are deciding deprivation cases using article 8 grounds even though this is considered later, at the point of deportation or removal (para 6.36).

Recommendations

Four recommendations were made:

Recommendation 1: Data recording. Review mechanisms for recording case data to ensure that record keeping is consistent, quality assured, and it allows for proper analysis to inform planning.

Recommendation 2: Decision making. Implement a plan to manage the backlog of cases ‘on hold’ to ensure they are allocated and promptly case worked once ‘blockers’ are removed.

Recommendation 3: Decision making. Conduct a review of benchmarks and work allocations for Executive Officer and Senior Executive Officer caseworkers to ensure that the Deprivation Team is managing its resources and outputs as efficiently and effectively as possible.

Recommendation 4: Training and guidance. Review the resourcing and role-specific training required by the training team to ensure they are equipped with the skills, knowledge, and resource to meet the needs of the department.

The Home Office accepted all four recommendations.

Conclusion

This appeals spreadsheet, with its partial, manual checks, has me wondering how they monitor the progress of appeals in asylum casework. Can it be worse than the process outlined in this report? Probably. One thing that it would be good to see rolled out elsewhere in the Home Office is the feedback loop between appeals and the decision making team. This is a really basic point that, as we can see from this report, can have a really positive effect on decision making.

SHARE