- BY CJ McKinney

Home Office urged to “professionalise” Presenting Officers

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

The Home Office should do more to “professionalise” the officials it sends to argue immigration cases in court, the immigration inspector has found. A report by the Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration, published today, says that Home Office Presenting Officers (HOPOs) need better training and more rigorous professional standards, as well lighter workloads that could be partly achieved by contesting fewer cases.

Presenting Officers are civil servants who present the Home Office’s case in immigration appeals. Although they appear before judges as the direct opponent of the lawyer representing the appellant, HOPOs are not usually legally qualified themselves. The report notes that Presenting Officers recruited from outside the civil service are no longer required to have a law degree on account of “the relatively high turnover of law graduates recruited to the role”.

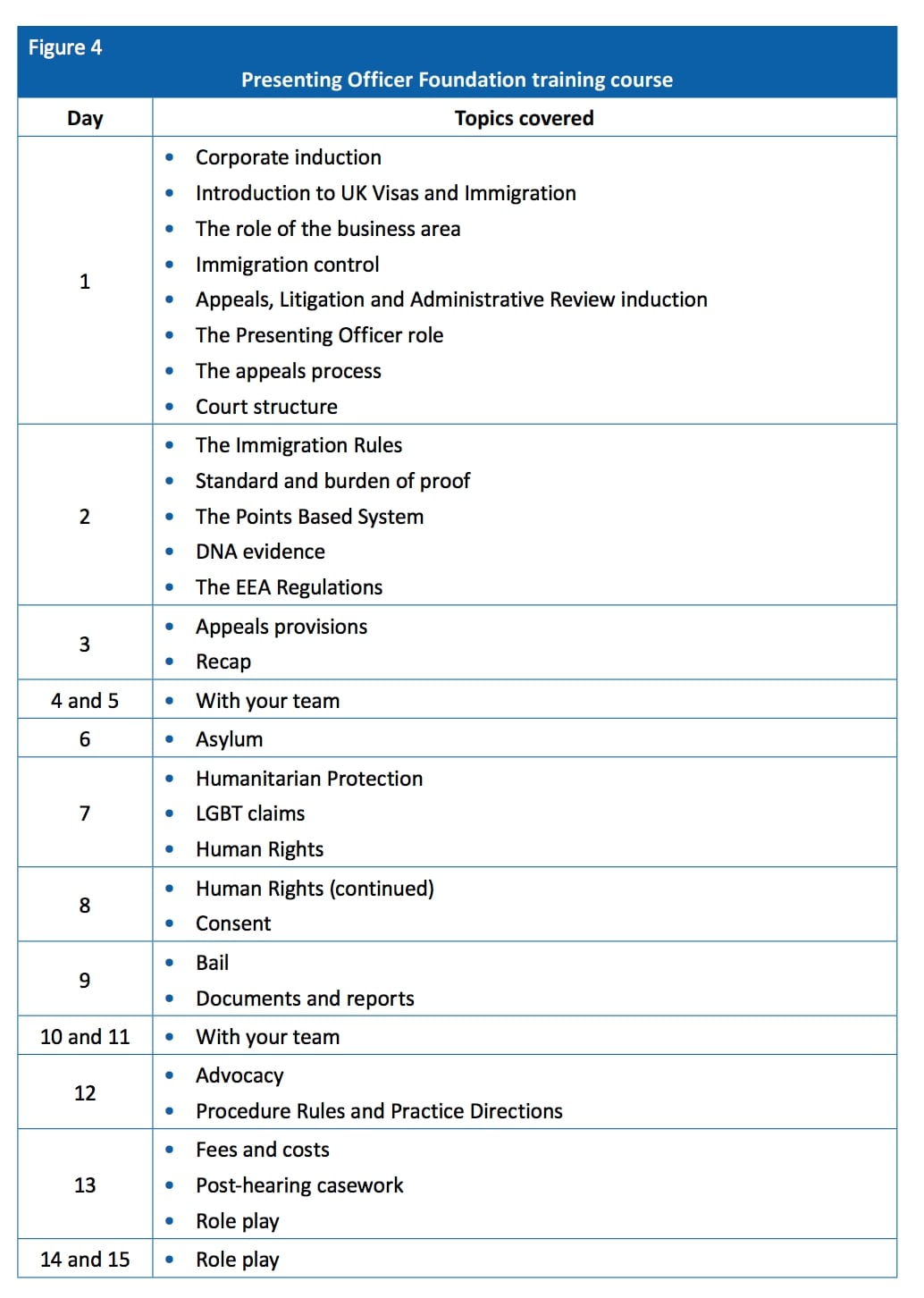

The chief inspector, David Bolt, canvasses an array of concerns about HOPO training and oversight that immigration lawyers have been raising for a long time. The Immigration Law Practitioners’ Association complained about HOPOs’ lack of detailed legal knowledge and “hostile and aggressive” cross-examination techniques that “often amount to more of a ‘fishing expedition'”. That is not necessarily surprising given that HOPO boot camp lasts only three weeks, where advocacy skills are covered in less than a day (see figure 4 below). HOPOs themselves “cited the training in advocacy and cross-examination skills as a particular weakness of the course”, Mr Bolt writes.

The need for training is particularly acute given the recent “shift in the composition of the appeals caseload… relatively simple entry clearance and family visit visa appeals have been replaced with more complex cases involving human rights issues and protection claims”. Individual HOPOs talk about a “vertical learning curve” and being “overwhelmed” in a “sink or swim” system. New HOPOs aren’t supposed to handle deportation cases before receiving their second round of training, three to six months in, but some were given deportations in error.

There does seem to be some consensus about the need for more training. The Home Office says that the foundation course is being extended from three weeks to ten weeks and has accepted the report’s recommendations for skills audits and development plans. It also plans to roll out “intensive mentoring” following promising pilot results (although lawyers may not be thrilled at this prospect since those results involved mentored HOPOs winning more cases).

Lawyers have long been vexed by the contrast between their weighty professional obligations and the minimal in-court rules for HOPOs. As former President of the Upper Tribunal McCloskey once described the position:

They are not officers of the court. They belong to none of the regulated professional cohorts. They do not enjoy the privileges and immunities of the advocate. They are not subject to any of the detailed codes regulating the professional and ethical conduct of advocates and others and, in consequence, they lie outwith the jurisdiction of the various regulatory bodies. Stated succinctly, HOPOs are unregulated.

HOPOs do have the Civil Service Code, but when it comes to professional standards specific to their role, all there seems to be is a two-page document described by Mr Bolt as “a curious mixture of exhortations, instructions and a dress code”. He recommends a proper code of conduct for HOPOing, as well as an overhaul of the “unsatisfactory” complaints procedure.

The inspector also notes that, while training and general professionalisation are important, what HOPOs need most is more prep time. An anonymous HOPO wrote on Free Movement last year of having just 90 minutes on average to read and prepare for each case. Over three-quarters of HOPOs surveyed as part of this inspection reported not having enough time to get ready for court.

Extra staff is the obvious solution, were money no object, but Mr Bolt puts more store in trying to reduce the number of appeals contested in the first place. One useful initiative is the email address for reconsideration requests, with the Home Office “withdrawing around 40% of the cases referred to the reconsideration inbox”. Another is the ongoing rollout of new-look online appeals where arguments are presented and considered much further in advance of a hearing:

The new processes that the Reform Programme is bringing in, including requiring submission of the detailed grounds for the appeal and skeleton arguments, should make a major contribution to the overall efficiency and effectiveness of the appeals process, since the Home Office should be much clearer at an earlier stage about the strength of the appellant’s case (and of its own).

This is expected to have a significant impact on the work of Appeals Operations, with more resources needed to review cases and, potentially fewer POs required and POs redeployed to review roles.

The holy grail is an effective feedback loop from HOPOs losing appeals to the decision-makers back at headquarters. Fewer incorrect refusals would mean fewer appeals lodged in the first place, freeing up Presenting Officers to give more time to the remaining cases.

Lawyers representing migrants may feel that well-rested, fully prepared HOPOs are the last thing their clients need. But there are obvious benefits to a more efficient service, such as HOPOs having time to talk over the case before the hearing starts to narrow the issues at stake. (Incidentally the internal professional standards document does instruct HOPOs to “attend court by 9:45 am… to facilitate any required discussions with Legal Representatives”.) Mr Bolt notes that “ultimately, it is in everyone’s interests that the PO function is properly resourced and supported, with well-trained, professional staff and reliable ways of working”.

The 105-page report concludes:

although the Home Office is making efforts to improve the PO function and the wider appeals process, there is more that it could be doing to professionalise POs, to connect up its processes, and to position itself with its key external stakeholders.

It makes six recommendations, all of them accepted by the Home Office.

Now read: I’m a Home Office Presenting Officer, ask me anything.

One Response

Related: Your questions answered by a Home Office Presenting Officer.