- BY Nadia O Mara

Briefing: why and how is the Home Office treating more asylum claims as “withdrawn”?

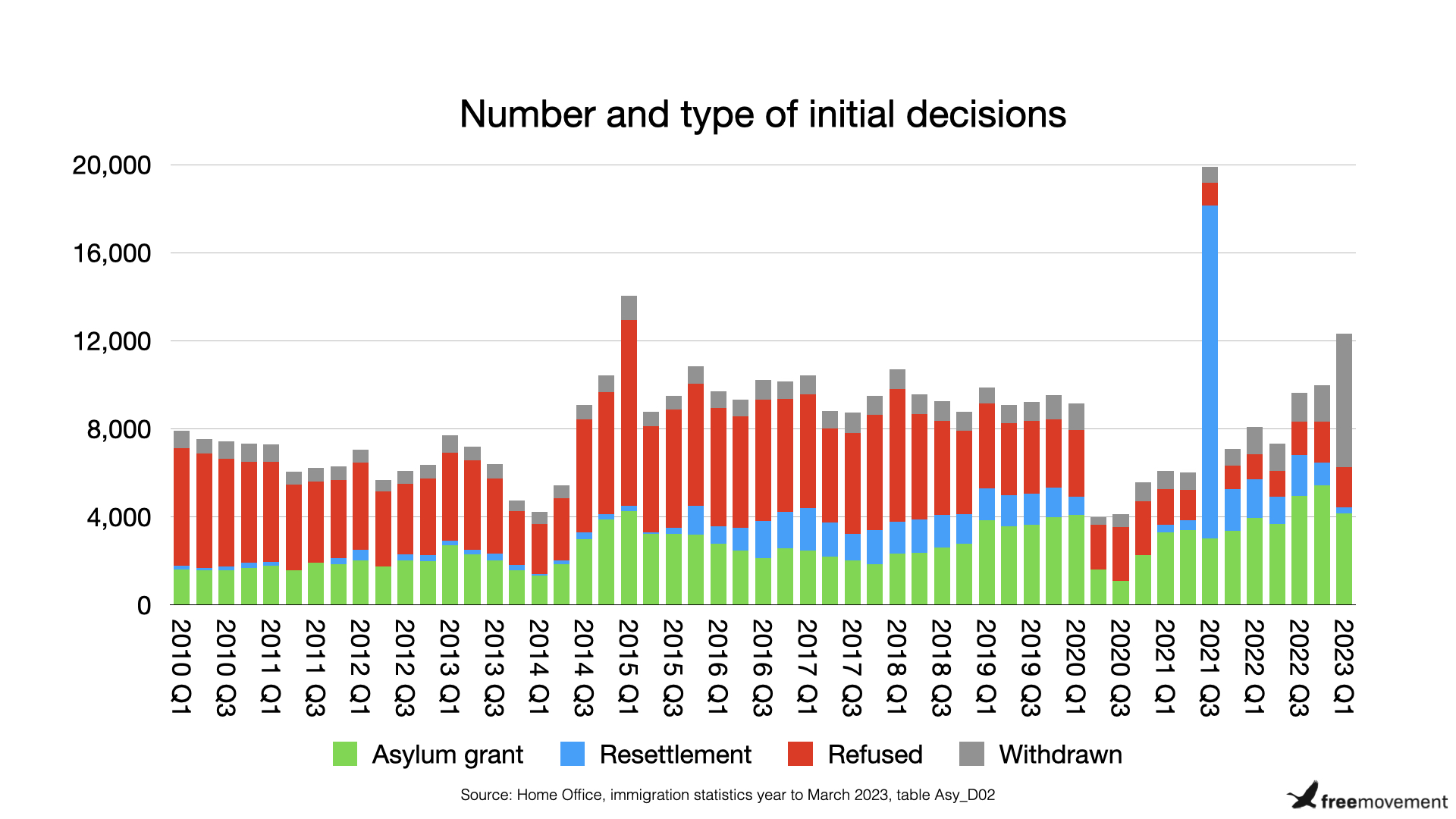

The Home Office is increasingly treating asylum claims as being withdrawn. This seems to be a new policy intended to reduce the asylum backlog. The number of asylum decisions made by the Home Office at first glance appears to be increasing. When we look at the detail of the figures, though, we can see that a growing number of those “decisions” are actually decisions to treat asylum claims as withdrawn.

Worryingly, the immigration rules have also now been amended to widen the circumstances in which officials can consider asylum claims to be withdrawn.

The previous version of the rule on treating asylum claims as withdrawn provides that an asylum claim will be treated as ‘implicitly’ withdrawn if the applicant leaves the UK without authorisation, fails to complete an asylum questionnaire, or fails to attend an interview (unless this was due to circumstances outside their control).

The new version adds two additional grounds:

- Failure to maintain contact with the Home Office or to provide up-to-date contact details; and

- Failure to attend reporting events unless due to circumstances outside the applicant’s control.

The circumstances in which an asylum claim will be treated as ‘explicitly’ withdrawn have also widened. Where before, the only circumstances in which a claim would be treated as explicitly withdrawn were where an applicant signed a specified form, an applicant may now also ‘otherwise explicitly declare a desire to withdraw their claim’ (whatever that means).

The Explanatory Memorandum to the new rules states that the changes to paragraph 333C are in order to ‘improve clarity’ regarding the withdrawal of asylum applications. It is difficult to see how adding yet further grounds will do anything other than increase the number of people who have their genuine claims for asylum thrown out without any substantive decision being made.

In an earlier post, Deborah Revill queried whether a ‘cynic’ might say that the more claims the Home Office can treat as withdrawn, the more it can say have been resolved as part of its pledge to beat the backlog by the end of 2023.

That cynicism is well-founded. A report published in June by the National Audit Office on the Home Office’s asylum and protection transformation programme revealed a stark increase in asylum claims treated as withdrawn.

The NAO report points to a near doubling in the number of weekly asylum decision, from about 690 in July 2022 to about 1,310 in April 2023.

However, 72% of decisions in April 2023 were ‘administrative decisions’ (including explicit and implicit withdrawals). Strikingly, in the case of Albanian nationals, 84% of decisions were ‘administrative decisions’.

Albanians are one of six ‘cohorts’ currently prioritised by the Home Office for expedited decision making. Even before this latest statement of changes to the Immigration Rules, Albanians were being singled out by a new Home Office policy requiring those who have claimed asylum to physically report to Home Office officials; the Home Office deeming a claim to have been withdrawn if there is a failure to attend without ‘good reason’.

Withdrawn asylum claims vs. non-compliance refusals

Paragraph 333C of the Immigration Rules and the Home Office API on Withdrawing Asylum Claims govern the circumstances in which asylum claims (and ‘protection based’ human rights claims: see paragraph 327 of the Rules) can be treated as either explicitly or implicitly withdrawn. Where the Home Office treats an asylum claim as withdrawn, consideration of that claim is discontinued without a substantive decision.

The newly amended version of paragraph 333C provides that:

333C. If an application for asylum is withdrawn either explicitly or implicitly, it will not be considered.

(a) An application will be treated as explicitly withdrawn if the applicant signs the relevant form provided by or on behalf of the Secretary of State, or otherwise explicitly declares a desire to withdraw their asylum claim.

(b) An application may be treated as implicitly withdrawn if the applicant:

(i) fails to maintain contact with the Home Office or provide up to date contact details as required by paragraph 358B of these Rules; or

(ii) leaves the United Kingdom (without authorisation) at any time before the conclusion of their application for asylum; or

(iii) fails to complete an asylum questionnaire as requested by or on behalf of the Secretary of State; or

(iv) fails to attend any reporting events, unless the applicant demonstrates within a reasonable time that the failure was due to circumstances beyond their control; or

(v) fails to attend a personal interview required under paragraph 339NA, unless the applicant demonstrates within a reasonable time that that failure was due to circumstances beyond their control.

(c) The applicant’s asylum record will be updated to reflect that the application for asylum has been withdrawn.

Confusingly, there is another very similarly provision under paragraph 339M which deals with ‘non-compliance refusals’. The similarity between the two rules lies in the fact that both paragraphs may apply where an applicant has not complied with Home Office processes, for example, a failure to report or a failure to complete an asylum questionnaire.

This post is concerned with withdrawals and paragraph 333C but it is important to understand the difference between the two rules because the avenues of challenge differ:

- First, non-compliance refusals can be made in asylum, humanitarian protection and all human rights claims.

- Second, non-compliance refusals under R339M deal with an applicant’s failure “without reasonable explanation, to make a prompt and full disclosure of material facts”, i.e., where a person has failed to substantiate their claim (for example, where their claim completely lacks detail or corroborating evidence). This is to be contrasted with claims treated as withdrawn, which is only concerned with failure to comply with processes.

- Third, and most importantly, because non-compliance refusals go to the substance of a person’s claim, the Home Office can never refuse a claim on grounds of non-compliance alone: there must always be a decision on the merits of the claim, however limited the available information (Haddad v SSHD [2000] INLR 117). A non-compliance refusal is therefore an appealable decision under section 82 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 (unless certified).

This is to be contrasted with withdrawal decisions, which the Home Office view as purely administrative decisions, from which no statutory right of appeal arises.

Perhaps unsurprisingly therefore, Home Office practice expressly favours treating claims as withdrawn and they are far more common than non-compliance refusals.

The Asylum Policy Instruction on Withdrawing Asylum Claims confirms this, stating (p. 16/31):

Claims that can be treated as withdrawn should not normally be refused on non-compliance grounds under paragraph 339M (which will generate a right of appeal). Any decision to refuse a claim on non-compliance grounds which could and should have been treated as withdrawn must be agreed by a senior manager (SEO or above).

Challenging decisions to treat an asylum claim as implicitly withdrawn

The policy instruction on Withdrawing Asylum Claims provides guidance about the circumstances in which a protection claim should be treated as withdrawn under paragraph 333C. At the time of writing, it has not yet been updated to reflect the changes to the rule.

Where the Home Office decides to treat a protection claim as withdrawn, they must notify the applicant and their immigration advisor (if applicable).

The first step when faced with such a decision is to work out whether the claim has been incorrectly withdrawn. If this can be established, the guidance is clear that the withdrawal must be cancelled, and the asylum claim will be reinstated and considered substantively.

The guidance provides a non-exhaustive list of circumstances in which it will normally be appropriate to cancel a withdrawal and reinstate a claim (pp. 26/31).

Let’s take one example. An applicant claims asylum with their spouse as a dependent. The relationship breaks down due to domestic abuse, and she is forced to move out of the address where she was residing. She is now staying at a refuge for victims of domestic abuse. The applicant is invited to an interview, but she never attends. The Home Office write to her old address, asking her to provide reasons for non-attendance, but she doesn’t respond. The Home Office notify her immigration advisor that her claim is treated as implicitly withdrawn under R333C for failure to attend the asylum interview.

Clearly, the applicant has missed the interview because of circumstances outside her control. To evidence this, the applicant should provide a witness statement explaining her situation and why she was unable to attend the interview. The refuge may be able to provide a letter, confirming that the applicant is staying at their accommodation. The applicant’s GP may be able to confirm that she has been referred for mental health support because of domestic abuse. The applicant may have made a report to the police and have a crime reference number.

Once the facts have been established and supporting evidence gathered, a pre-action letter should be sent to the Home Office challenging the treatment of the claim as withdrawn and requesting that the applicant’s address be updated. Hopefully, the Home Office recognise the error and cancel the withdrawal decision. If not, judicial review proceedings will need to be issued.

If none of this bears fruit, and in the absence of a statutory right of appeal, then the only option available to an applicant is to prepare a fresh claim. Further submissions or a ‘fresh claim’ is the process of submitting an asylum (or human rights) application where there has been a previous failed claim and all appeal rights have been exhausted.

The test for what constitutes a fresh claim is found in paragraph 353 of the Immigration Rules Any new evidence submitted will only be considered a fresh claim if it meets two criteria:

- It has not already been considered, and

- Taken together with the previously considered material it creates a realistic prospect of success.

In the case of a claim treated as withdrawn, the first criterion will likely be easy to satisfy. Where, for example, an applicant’s claim has been treated as withdrawn because they failed to attend an interview or complete a questionnaire, the Home Office will not have previously considered the substance of their claim.

However, to be considered a ‘fresh claim’, the applicant must also show a ‘realistic prospect of success’. For applicants from countries with lower recognition rates, this may pose a significant hurdle to overcome, and those preparing such fresh claims will need to ensure that the evidence submitted is not only new but is also enough to argue that the claim would have a realistic prospect of success on appeal.

Guidance on preparing a fresh claim can be found here and if you need more detail than that a short course is also available on Free Movement:

| Module 1 | Law and process | |

|---|---|---|

| Unit 1 | Introduction | |

| Unit 2 | The rules on fresh claims and what they mean | |

| Unit 3 | The fresh claim process | |

| Module 2 | Fresh claims in practice | |

| Unit 1 | Understanding the client's situation | |

| Unit 2 | Change in country situation | |

| Unit 3 | Change in client's situation | |

| Unit 4 | Further and better evidence cases | |

| Unit 5 | Poor representation in the previous case | |

| Unit 6 | Expert reports | |

| Unit 7 | Final quiz |

Conclusion

Treating asylum claims as withdrawn is not new. However, recent Home Office practice and the statement of changes to the Immigration Rules suggests these decisions are on the rise. Unfortunately, all this will likely achieve is to cause misery to those caught out, delay the eventual consideration of their claim and further burden decision-makers. The number of fresh asylum claims and judicial review claims will likely increase, a significant proportion of which will be successful.

Treating an asylum claim as withdrawn does not magically make the person concerned disappear. They are still here. They will need to be dealt with some time. They cannot be removed without some assessment of whether it is safe to do so. The Home Office may be saving itself some effort in the short term and reducing the apparent asylum backlog. But they are doing so at the expense of creating more work in the long term.

2 responses