- BY Colin Yeo

Briefing: the sorry state of the UK asylum system

Table of Contents

ToggleIn this briefing we will take a look at what is really going on with the main features of the contemporary asylum system: arrivals, the backlog, detention, removal and resettlement. The focus is on what caused the backlog and what consequences will flow from the large number of decisions being made. The information is drawn mainly from the quarterly immigration statistics and transparency data for the year ended June 2025, the most recent available at the time of writing.

The picture the data presents is of a system that has been overwhelmed. Not by new arrivals but by mismanagement.

After the ban on grants of leave to those in the inadmissibility process was lifted following the change in government last year, there has been progress on making initial decisions on asylum claims. However the emphasis on fast decision making is coming at the cost of accuracy and quality.

This means that the Home Office is merely shifting asylum cases into a second backlog, this one in the tribunal system. By directing the backlog in this way, the Home Office has managed to deflect much of the blame, with recent government focus on “tribunal system reforms” rather than making initial decisions that are sustainable.

The backlog is the single most important problem with the asylum system. Unlike arrivals, it is something the government can control. It creates huge financial costs for the taxpayer. It sucks money out of the international aid budget. It distracts ministers and officials from other issues. The thought of asylum seekers staying in hotels is politically toxic. It is also terrible for the refugees waiting interminably for a decision. Their lives are on hold, they live in destitution-level support in poor accommodation and they are prevented from working or doing anything productive.

Eventually around three quarters of them will be recognised as refugees and become permanent members of our society. Making their lives so miserable and difficult rather than helping them get on their feet is not a good idea for any of us. And, as we will see, barely anyone who is refused asylum is removed from the UK anyway.

The only group to benefit from the long waiting times are those whose cases will ultimately fail; by the time that happens they will have been living here for years and it will be even harder for the government to remove than would otherwise have been the case.

Asylum arrivals

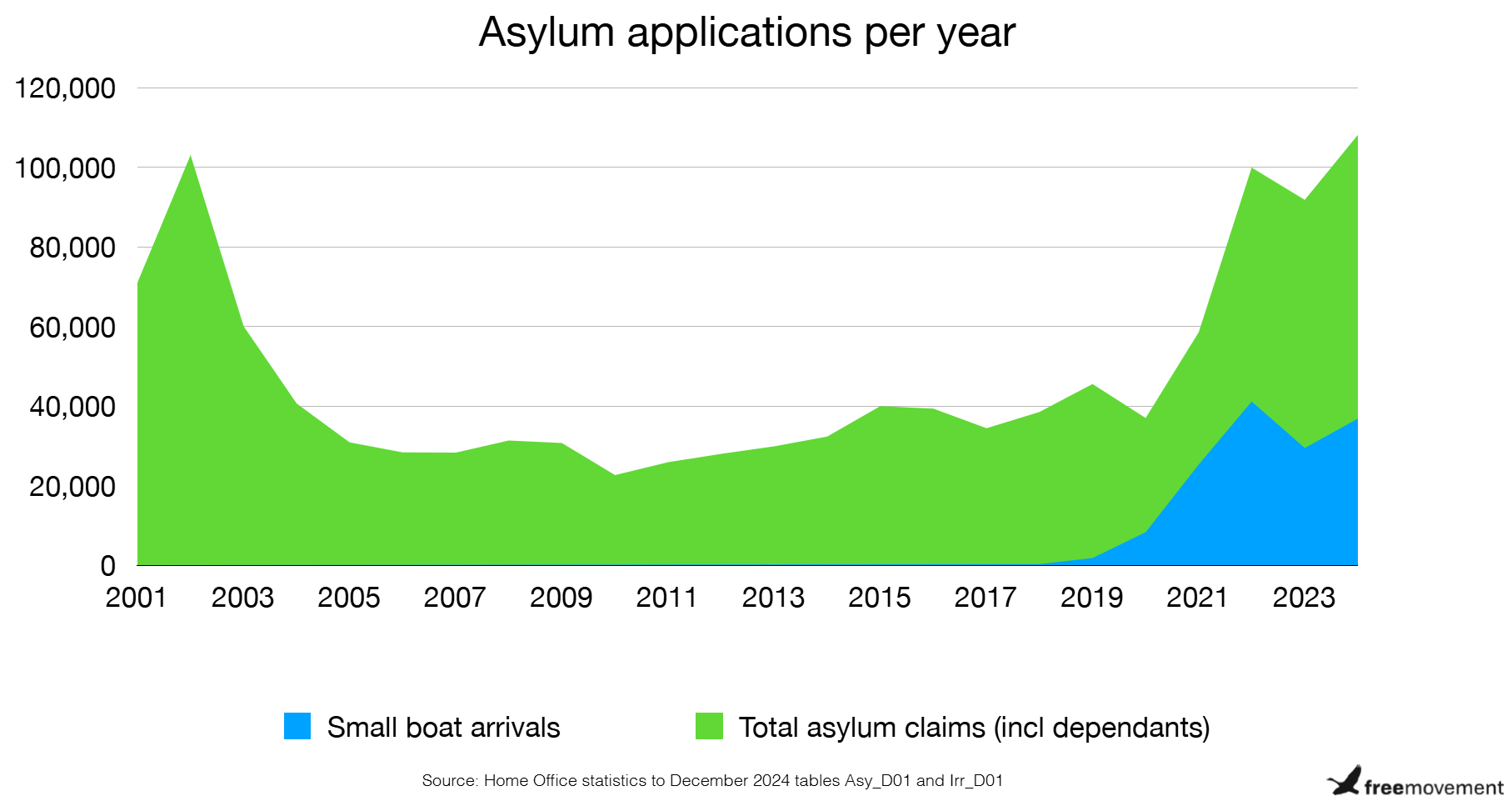

Following a significant peak in 2002, the number of asylum applications made in the United Kingdom was fairly stable between 2005 and 2020. The Syrian refugee crisis beginning in 2014 caused a slight rise in overall numbers.

The number of asylum applications increased significantly in 2021, including increasing numbers of people arriving by means of small boats.

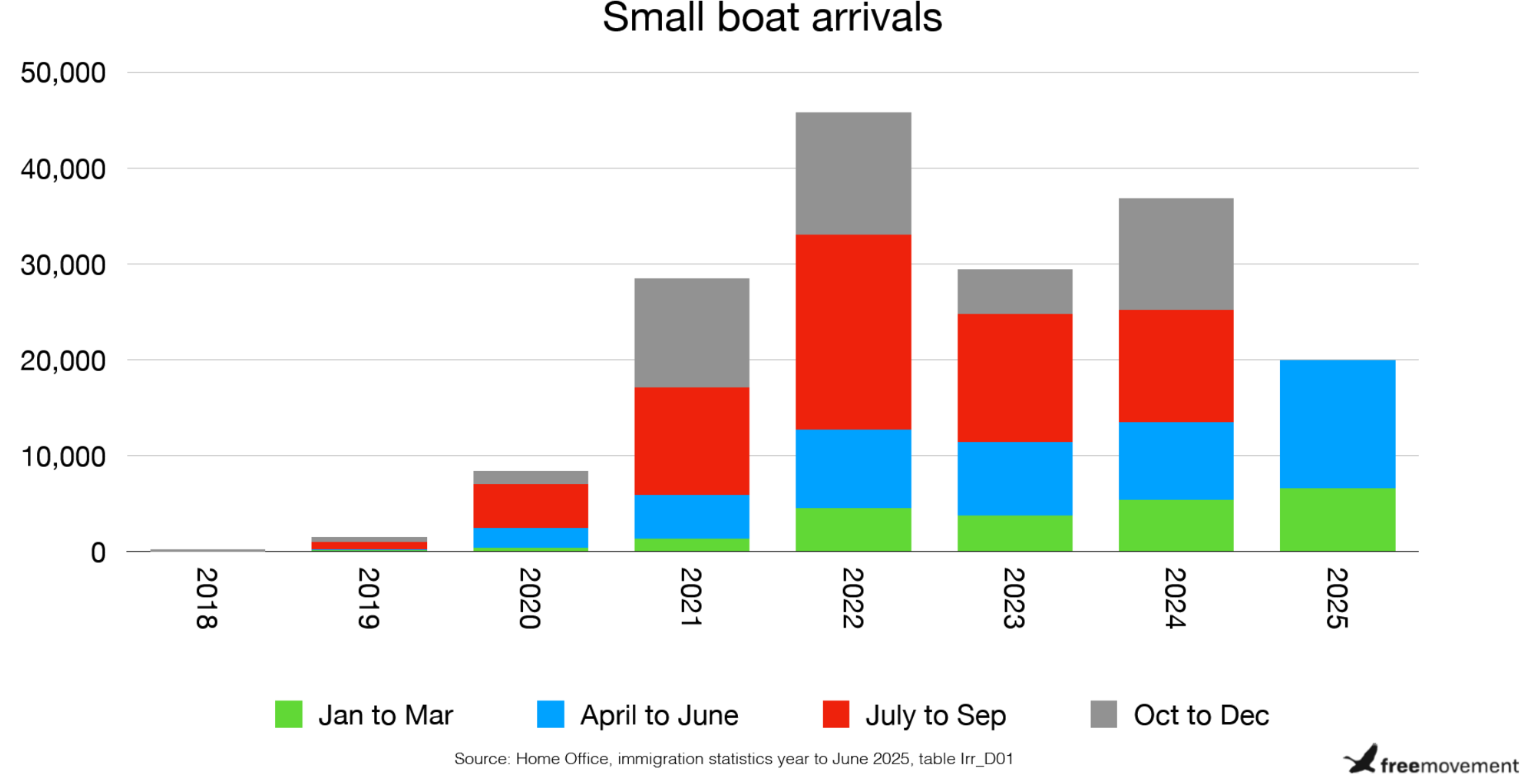

The number of small boat arrivals can be seen to have increased sharply from nowhere in 2018. Previously, lorries had been the principal means of entry to claim asylum. The following chart shows overall numbers and also gives you an idea of arrivals by quarter.

The drop in 2023 compared to 2022 is almost entirely due to the rapid increase and then equally rapid decrease in arrivals by Albanians during 2022. In effect, this inflated the 2022 figures quite considerably, although we can see a further increase in 2024 that was not driven by Albanians, but by Afghan nationals.

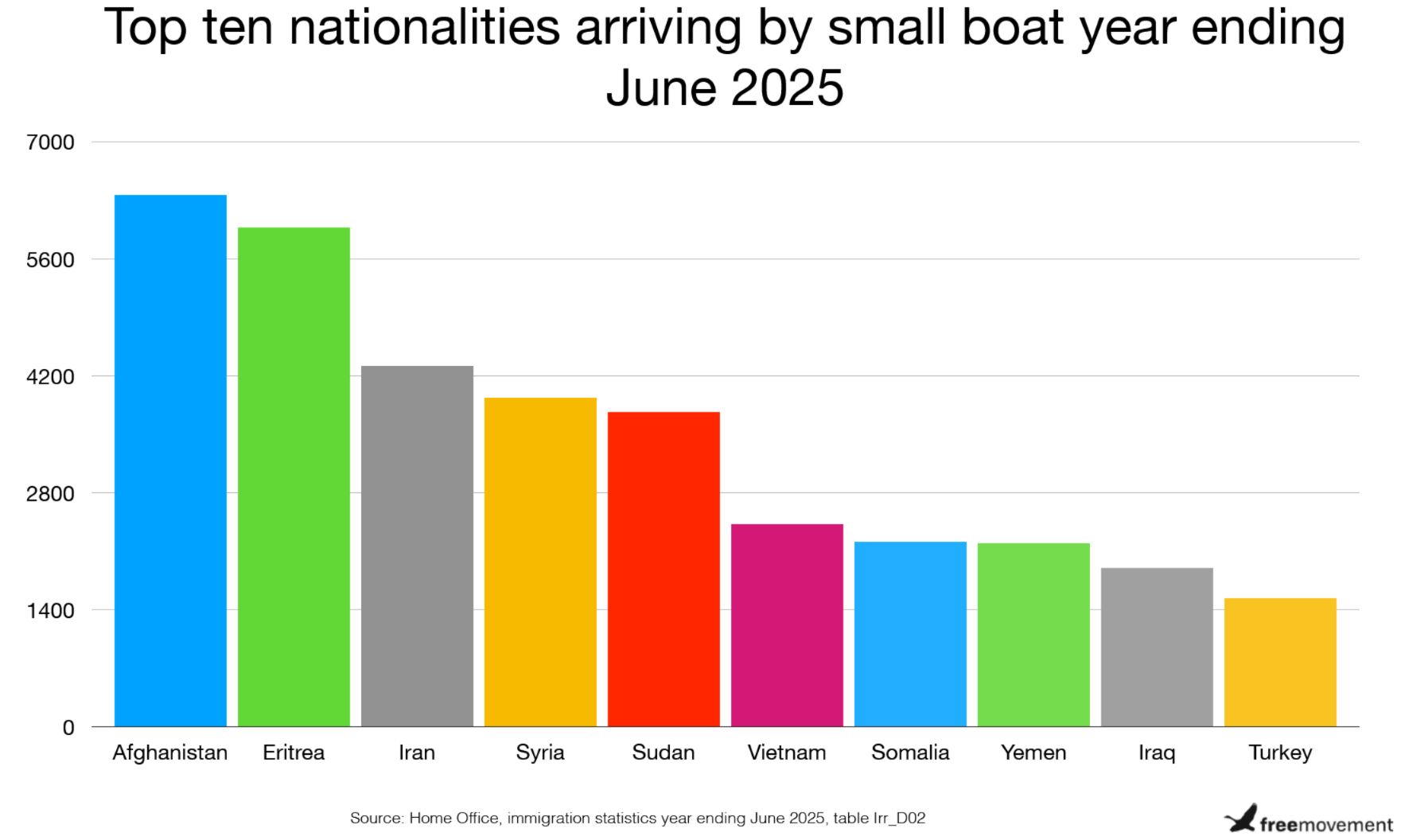

In the year ending June 2025, Afghan and Eritrean nationals have been crossing the Channel in the highest numbers.

Asylum backlog

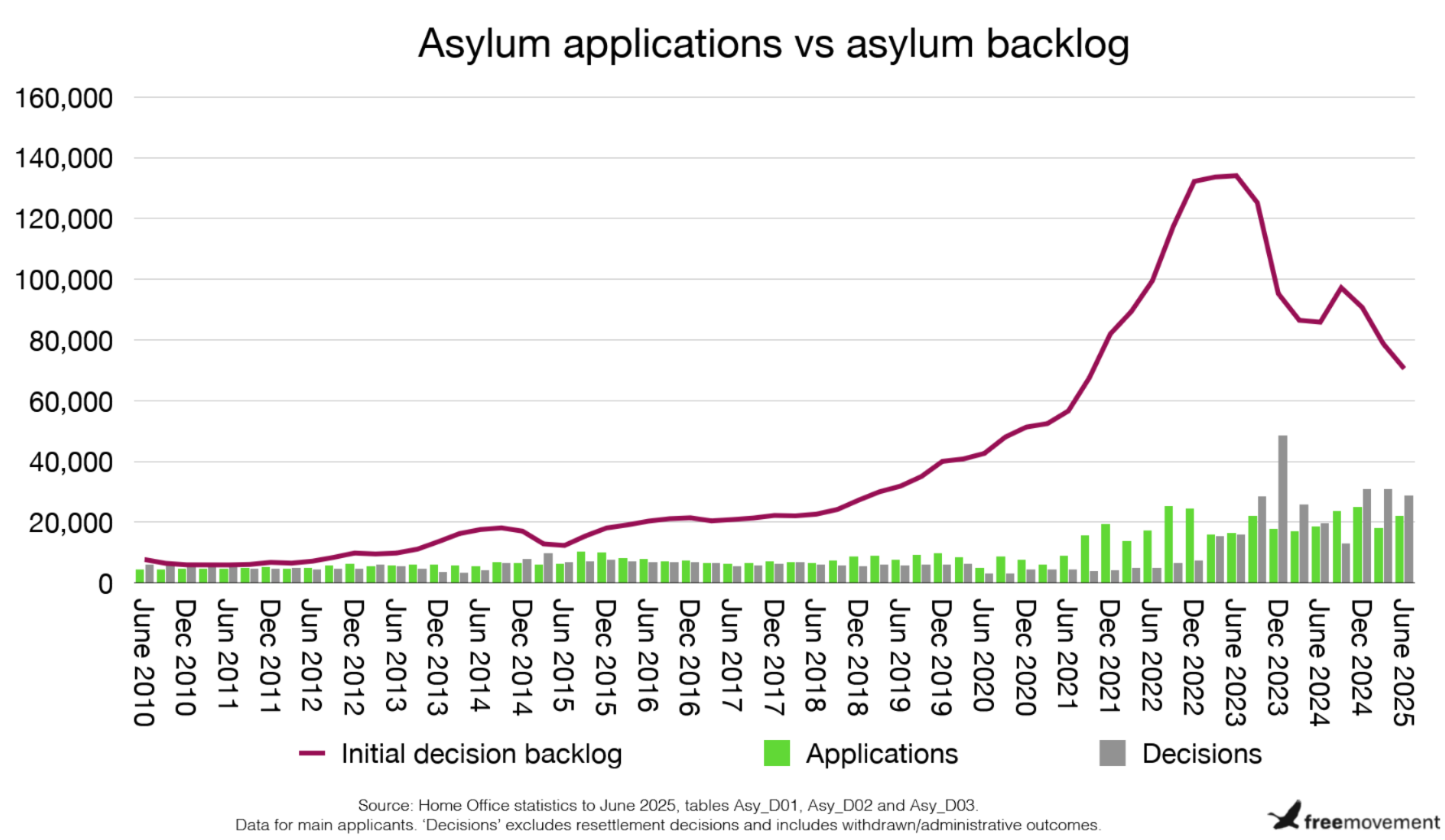

The stand out problems of the asylum system today are the high number of poor quality refusals and the asylum appeals backlog. These are recent developments that, unlike small boat arrivals, lie almost entirely within the control of the Home Office.

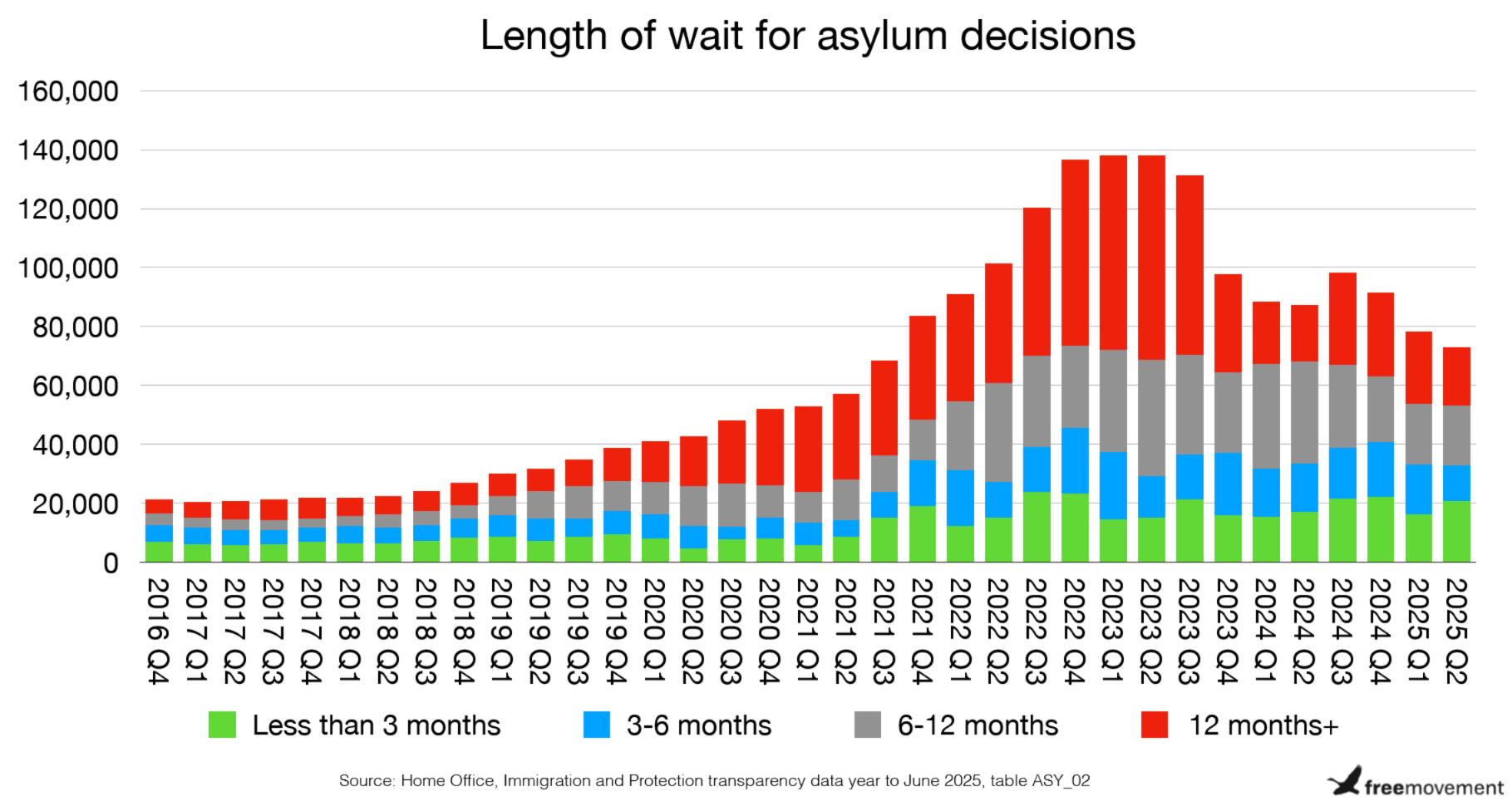

The initial decision backlog is trending downwards, the slight increase in the period to September 2024 was related to the work required to get cases moving again.

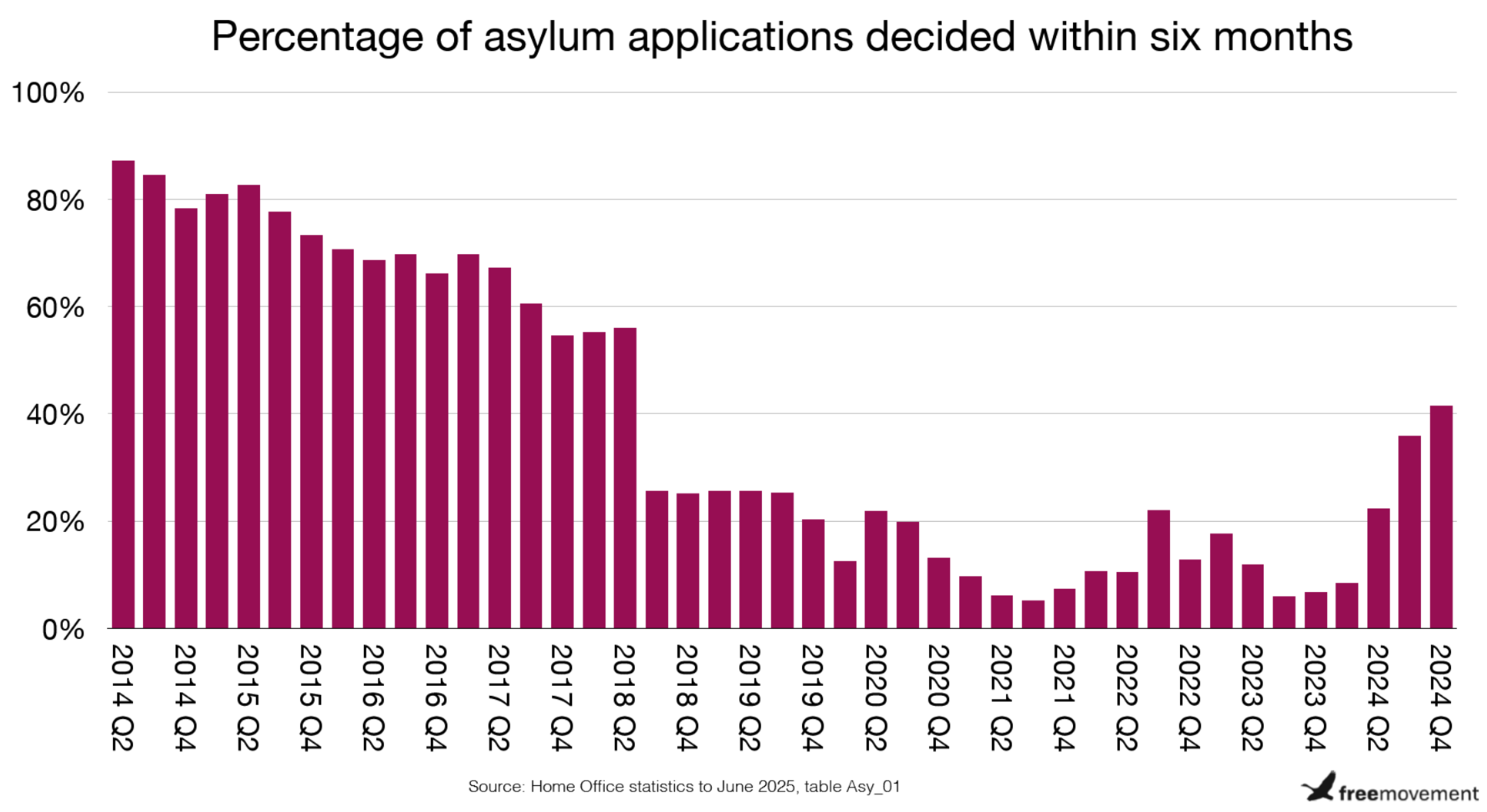

We can see the root cause of the current asylum backlog lies back in 2018, when the percentage of asylum cases decided within six months suddenly plummeted. The proportion of decisions made within six months increased substantially, to over 22% in the period April to June 2024 which is the most recent published data and pre-dates the Labour government, which has made speeding up decision making a priority.

As at June 2025 there were over 19,000 people who have been waiting for longer than a year for an initial decision. This is really expensive because they are not allowed to work, and so have to be supported by the government.

Because the backlog was allowed to grow, the Home Office ran out of ordinary asylum accommodation long ago and has had to resort to using hotels. The international aid budget has been plundered in order to fund this. Immigration fees have been ratcheted up yet again in order to plug the hole in the Home Office budget.

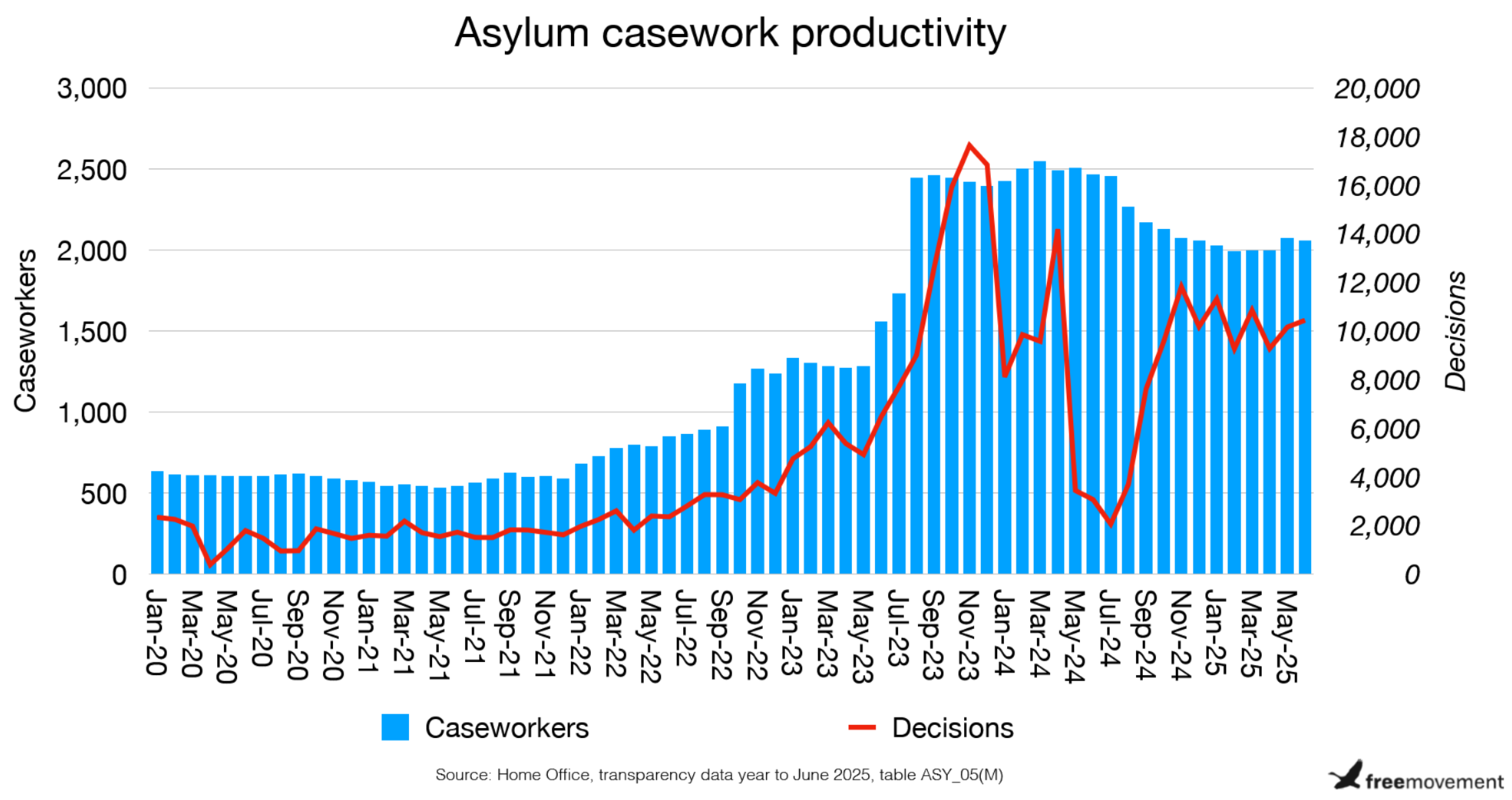

To deal with the backlog, the government decided to recruit more officials to decide asylum claims. Braverman, during her second stint as Home Secretary, said she planned to have 1,300 caseworkers in place by March 2023, a target she managed to hit. Sunak then pledged in December 2022 to double the number then in place, which would mean reaching a total 2,400 caseworkers. That number was hit in August 2023 and after peaking in March 2024 the number of caseworkers has decreased since then, to 2,057 at the end of December 2024.

Towards the end of the legacy backlog clearance exercise, many of the decisions were made without conducting an interview. We can see from the transparency data that 16,828 decisions were taken in December 2023 but only 4,893 interviews.

The pendulum then swung very much in the opposite direction, as the number of interviews substantially outnumbered decisions in August 2024 (3,688 decisions and 10,327 interviews), September 2024 (7,608 decisions and 11,540 interviews) and October 2024 (9,563 decisions and 11,146 interviews). Now, we know that decisions and interviews will not always be recorded on the same case in the same month, however practitioners raised concerns at the time about the Home Office’s move to carrying out multiple interviews on the same case.

As of November 2024 there were again more decisions that interviews, and in December 2024 there were 10,112 decisions and 6,442 interviews.

Part of the problem may lie with the fact that the Home Office recruited a large number of inexperienced decision makers. The analogy that comes to mind is with policing; around 20,000 police officers were cut in the austerity years after 2010. The government then announced it would recruit new police officers. 20,000 of them, as it happens. But they are not like-for-like replacements. They are inexperienced rookies who require training. They are less productive and need to learn the ropes.

The appeals backlog

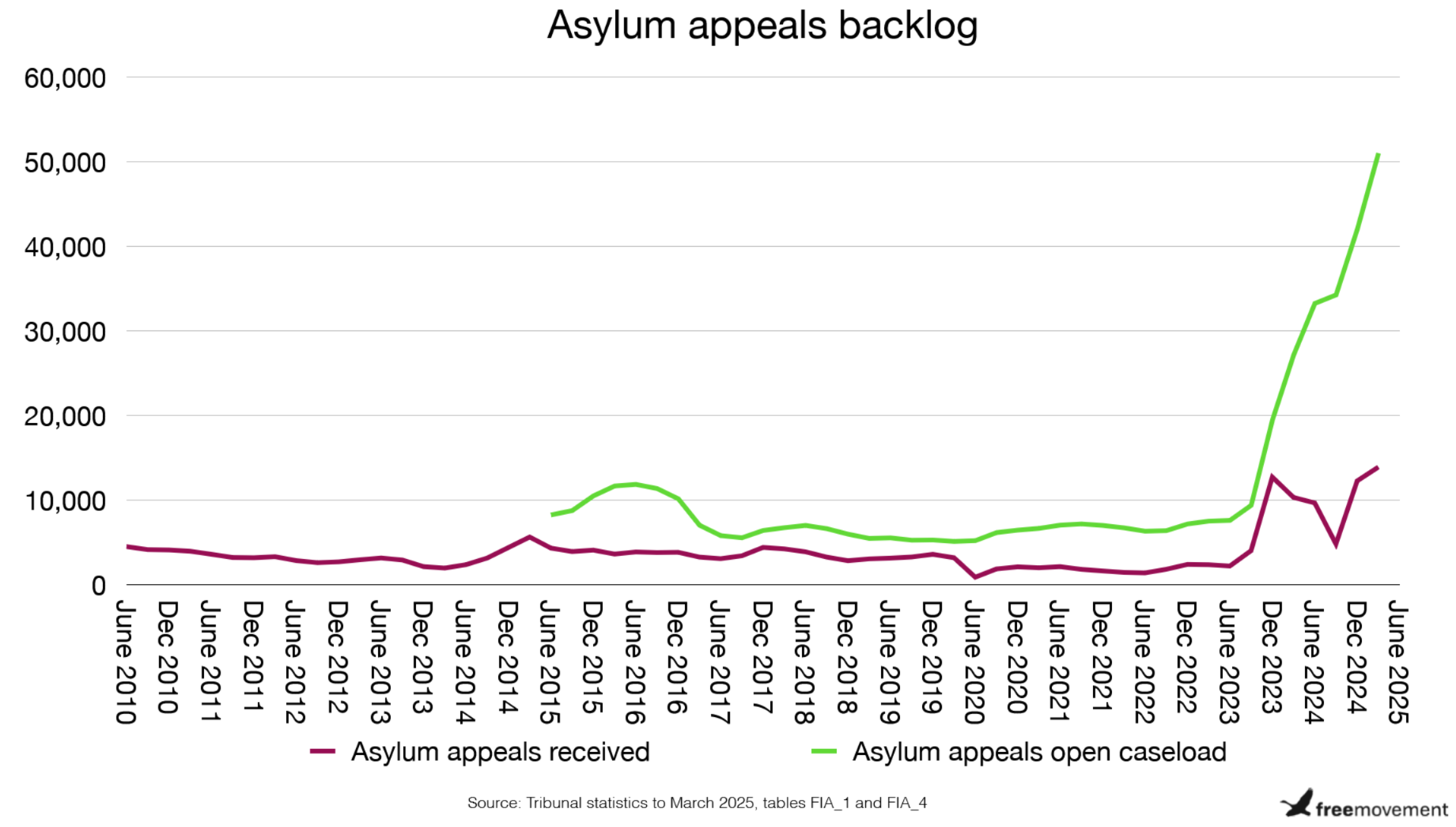

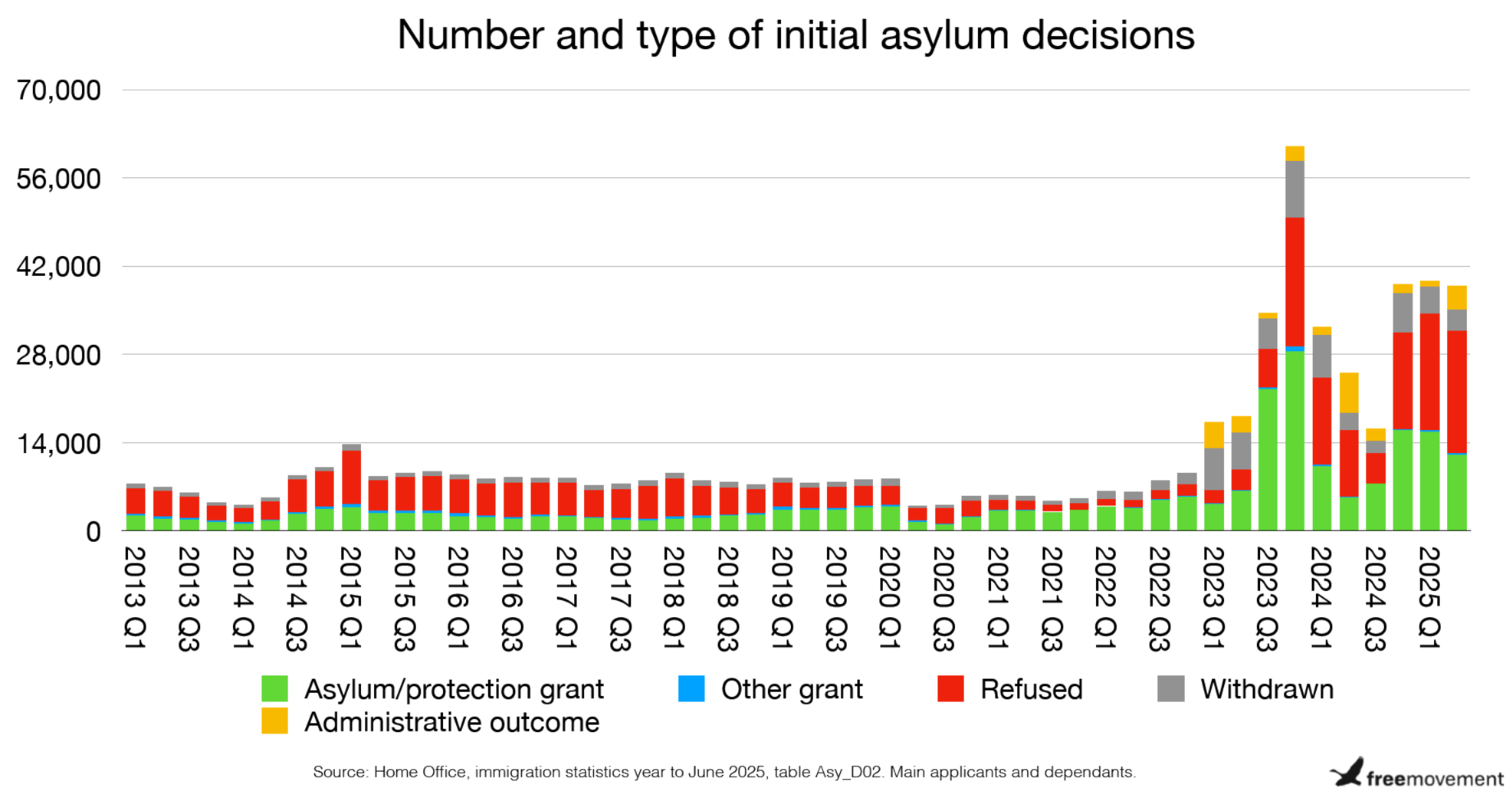

Because of the sheer number of decisions being made, there are also now a lot of people being refused asylum: 57,905 in the year ending June 2025. We have already seen that the number of asylum appeals being lodged has increased significantly and in the year ending March 2025 the First-tier Tribunal received 40,667 asylum appeals up from 29,290 the year before.

There are a few factors in particular which have contributed to the backlog of cases in the tribunal. There have been two distinct periods where the Home Office was refusing few cases, and these were then followed by a very high number of refusals.

The first was during the backlog clearance exercise in 2023 and the second was a combination of lifting the inadmissibility pause and an extremely large drop in the grant rate of initial asylum claims. We look at each of these points in more detail below, as well as other contributing factors including the quality of Home Office decisions and the lack of legal aid lawyers.

Increase in refusals: backlog clearance

When carrying out the backlog clearance clearance exercise in 2023, the Home Office initially focussed on easy grants and so prioritised claims from high grant countries. Refusals were left to the latter part of 2023, the effect of which was a huge increase in the number of appeals being lodged within a short period of time.

The number of asylum decisions soared in the fourth quarter of 2023 to an astonishing 49,094 proper decisions plus a further 9,087 withdrawals of asylum claims. There were 28,231 grants of asylum and 19,997 refusals.

We can then see that there was a drop in the number of appeals being lodged, this was because the Home Office had largely stopped processing asylum claims because of the use of the inadmissibility process.

Increase in refusals: resumption of processing of asylum cases but with a very low grant rate

Once claims held in limbo in the inadmissibility process started moving again, we can see above that this led to another spike in the number of appeals submitted. This time the huge increase was driven not just by the number of decisions being made as with the backlog clearance, but because this was combined with a dramatic fall in the grant rate at initial decision stage.

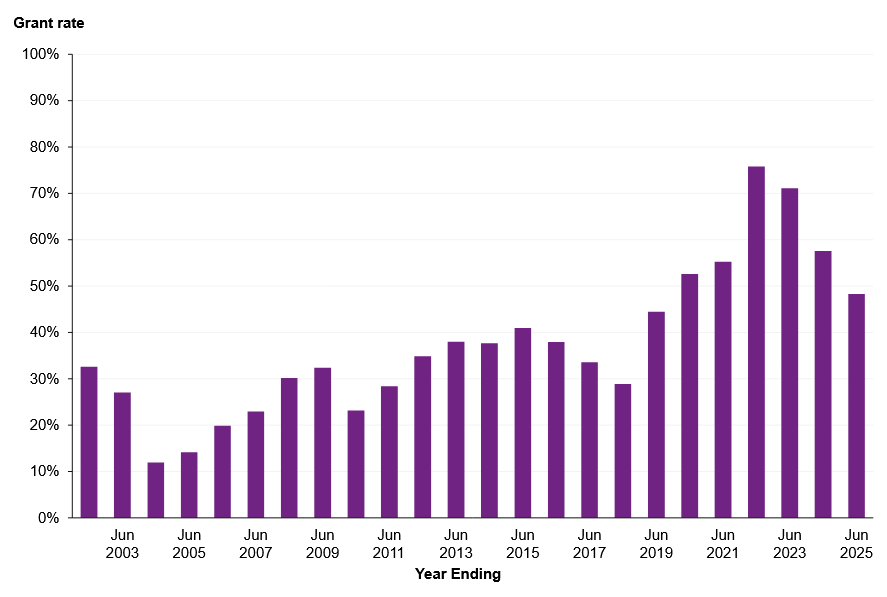

In 2022, 76% of initial asylum decisions by the Home Office were grants of protection. As a percentage, that is an historic high not seen since since the 1980s, when there were far fewer asylum claims being made. It is therefore not completely surprising that the grant has dropped, although the size of the drop, to 48% in the year ending June 2025, indicates a problem.

It is also worth noting that this grant rate is calculated by the Home Office only using grants and refusals data, and excludes cases which are deemed withdrawn or that have an “administrative outcome”. When that data is taken into account, the asylum grant rate is even lower.

The Home Office explains the drop as being the result of the increased standard of proof required under the Nationality and Borders Act 2022, which applies to claims made on or after 28 June 2022. Instead, practitioners have been raising concerns about the quality of Home Office decisions, concerns that are backed up by the Home Office’s own data as discussed further below.

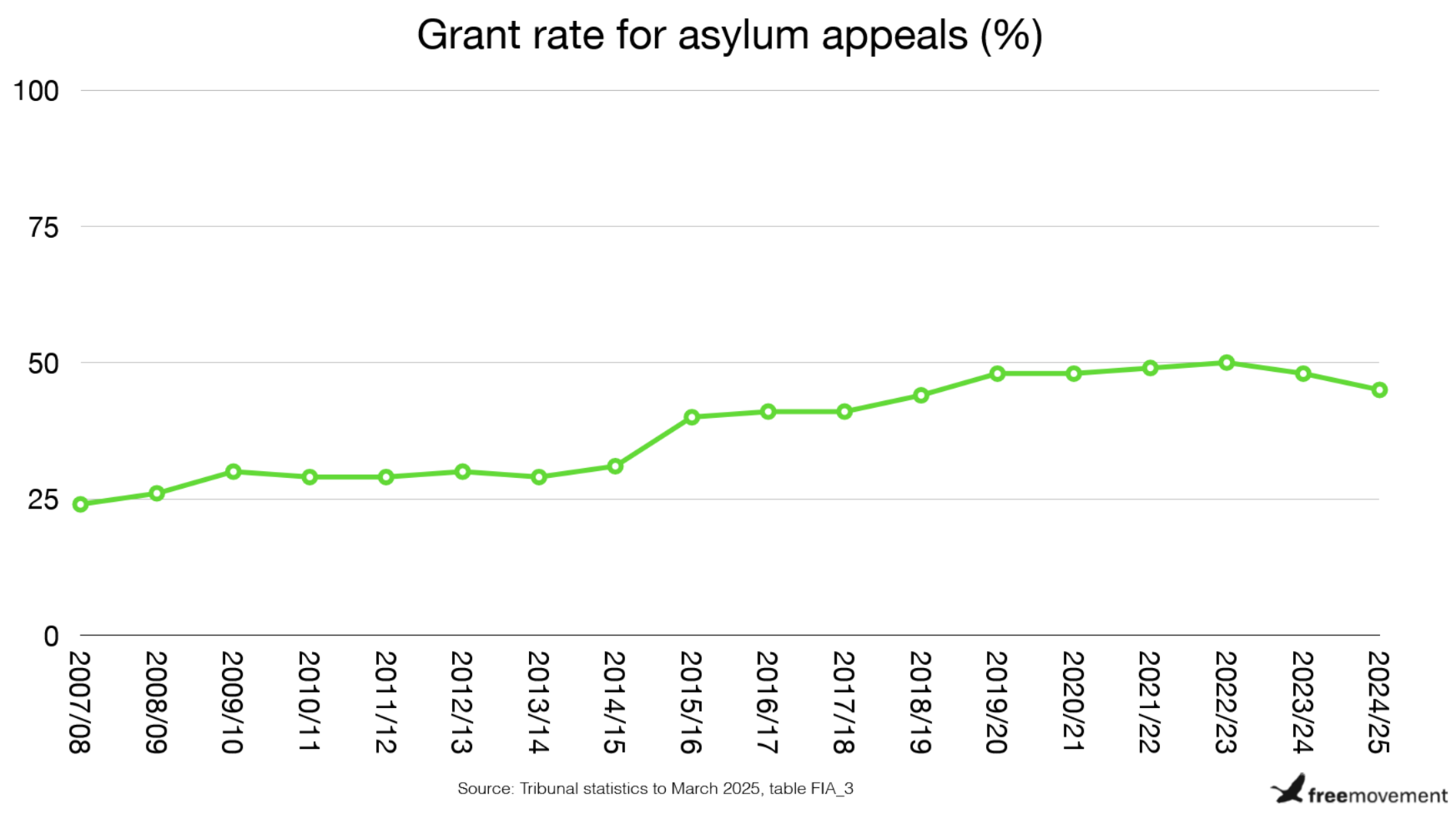

Appeal success rate and processing times in the tribunal

We might expect the appeal success rate to increase because of the dramatic increase in refusals and associated concerns about the quality of those decisions, but because appeals take a long time to be determined, it will take a while to see any impact in the data. The increase in unrepresented appellants because of the lack of legal aid lawyers will also have a downward impact on appeal success rate and this may be difficult to quantify, which is of great concern.

The average time it takes for the First-tier Tribunal to decide an asylum case was 50 weeks in the period January to March 2025, up from 43 weeks for January to March 2024. We can expect that to continue to increase as the additional appeals work their way through the system.

It was inevitable that the asylum caseload at the tribunal would increase as a result of increased Home Office decision making but it seems this has not been matched by increased resources for appeals. When we say increased resources for appeals, we don’t just mean more judges.

Lack of legal aid lawyers

There is a further problem which greatly exacerbates the appeals backlog: there are no lawyers left. That’s because legal aid rates are so low that lawyers cannot afford to do the work any more. This may well be a cause for celebration for some, but it risks serious unfairness and causes significant problems to the tribunal system (it is also a likely contributor to the significant drop in grant rates at initial decision stage).

Already, even before the increase in the number of appeals being lodged, around half of asylum seekers were unable to find a legal aid lawyer. That proportion is going to fall. We don’t grow on trees and last year’s announcement of an increase has yet to materialise. Even once it does, assuming it is sufficient to enable the sector to grow rather than merely to slow the decline, it will take time to expand the pool of available legal aid lawyers.

The lack of lawyers means that many asylum seekers will go unrepresented. As well as being unfair and risking bad outcomes, including return of refugees to situations of persecution, it builds in additional delays and will make it much harder to reduce the appeal backlog.

It takes a lot longer for judges to deal with appeals where there is no lawyer involved as unrepresented appellants are unable to identify the relevant legal arguments and evidence, and there will be other barriers to effective participation, such as language and technological barriers.

Poor quality Home Office decisions and missing data

As mentioned above, concerns were raised about the quality of decision making towards the end of the backlog clearance process and have continued since. Practitioners have reported that evidence submitted to the Home Office before asylum interviews was not being considered and that interviews are being truncated to the point that people are not able to put their case across properly. These errors are clearly occurring at scale and all that does is transfer the asylum backlog from the Home Office to the First-tier Tribunal.

Poor quality decision making is not merely anecdotal, it is backed up by the Home Office’s own checks and data, at least what there is of it. The Home Office’s data on internal decision quality checks shows that these have dropped to a woeful 52% passing the checks in the year 2023/2024.

As I have pointed out elsewhere, the Home Office has now failed to publish the most recent statistics on their quality checks, so we are missing data for the year 2024/25 which was due to be published in August.

Other data that relates to the sustainability of Home Office decisions which has gone missing is the Home Office data on appeals which has not been updated since the beginning of 2023. This gives a much more detailed breakdown than the tribunal’s statistics, including important information such as nationality.

Looking at Afghan cases is useful here, as the initial decision grant rate dropped from 96% to 40% in the space of a year. The vast majority of those cases are likely to have moved into the tribunal system, but what is happening to them there? How many of those decisions is the Home Office withdrawing at appeal stage, after deciding that they are unsustainable? How many Afghan nationals are succeeding at appeal? We have no idea, because the Home Office has stopped publishing the data.

What happens to the people in the asylum system?

This rapid increase in decisions means there are other significant problems in the asylum system:

- What happens to the person behind withdrawals of asylum claims or “administrative outcome”? Most of them remain in the country.

- What happens to the people who are newly recognised refugees or have been granted another form of leave? They get very short notice before they are evicted from asylum accommodation, which is insufficient time to find a job or accommodation, so they end up homeless and supported by their local authority.

- What happens to failed asylum seekers at the end of the process? Very few are removed.

Let’s consider each of these in a bit more detail.

Are asylum withdrawals really a “decision”?

Since the start of 2023 there has been a huge increase in withdrawals of asylum claims. This process initially seems to have targeted Albanians with 14,371 withdrawn claims from this group over 2023 and 2024, out of a total of 44,111 withdrawn claims.

That proportion dropped in 2024 although it remained significant. In 2024 3,633 of the 17,810 withdrawn claims were from Albanians. The next highest was India with 3,257 withdrawn claims, then Vietnam (1,835) and Brazil (995). What we don’t know is how many withdrawn claims are subsequently being reinstated, although we have seen some successful legal challenges (for example this Albanian case and this decision by the Asylum Support Tribunal).

A National Audit Office report in June 2023 revealed that many of these ‘withdrawals’ were actually what lawyers call non-compliance refusals: the asylum seeker failed to return a form on time, did not turn up to an appointment or something like that. Some asylum seekers may genuinely have deliberately disappeared. But experience suggests the Home Office is bad at logging changes of address, posts things to the wrong address anyway and that a certain proportion of these decisions will turn out to be wrong.

This creates a significant long term problem. Many of those treated as ‘withdrawn’ will still be in the UK and will resurface. They may lodge a judicial review of the withdrawal decision, or an appeal to the Asylum Support Tribunal where appropriate, if they think it was a mistake by the Home Office or otherwise they will make a fresh claim for asylum. They will become complex cases and will take additional resources to process. The Home Office may be making more work for itself in the long run by trying to hit its short-term targets. This would be entirely typical behaviour by the department.

Their case papers may have been taken off the books and out of the backlog but the actual human beings behind those cases have not disappeared and at some point their cases will need to be considered. In the meantime, with no rights in this country, they face being exploited in order to survive.

What happens to all the newly recognised refugees?

In the year ending June 2025 51,997 people were granted refugee leave or another form of leave. All of those people moved from being supported by the Home Office to either standing on their own two feet or being supported by their local authority. Or they fell through the gap and ended up homeless.

After several years of enforced unemployment, it is no surprise if only a small percentage manage to find a job in the short space of time the Home Office gives them between issuing their new immigration papers (or eVisa as is now the case) and evicting them from their asylum accommodation.

Refugees are given 28 days between being issued their immigration papers and being evicted from their asylum accommodation. It is impossible to find a job, be paid and find accommodation in that time. The short timescale also makes it very hard to get support from the relevant local authority. As a result, local authorities are finding themselves having to accommodate thousands of refugees at basically no notice.

The current pilot to double this period to 56 days is therefore welcome news [Ed: which is probably why it has just been announced today that they are discontinuing it], although the Home Office does seem be tying it to the eVisa roll-out, which has not been going very smoothly to say the least, and sorting out access to that is likely to eat into at least some of those 56 days.

Some idiots will claim that refugees becoming homeless just goes to show how they are a drain on public resources. If we keep them waiting for years in remote locations, prevent them from working during that time and do everything in our power to prevent them integrating and then give them virtually no notice that they are to be granted status and evicted from their accommodation, of course they are going to struggle even more than they might have otherwise.

Local authorities need urgent funding. Central government should allow refugees to find jobs if they’ve been waiting for longer than six months, permanently give them a longer notice period before evicting them from asylum accommodation and offer an integration package, for example including language and career training.

Refusal ≠ removal

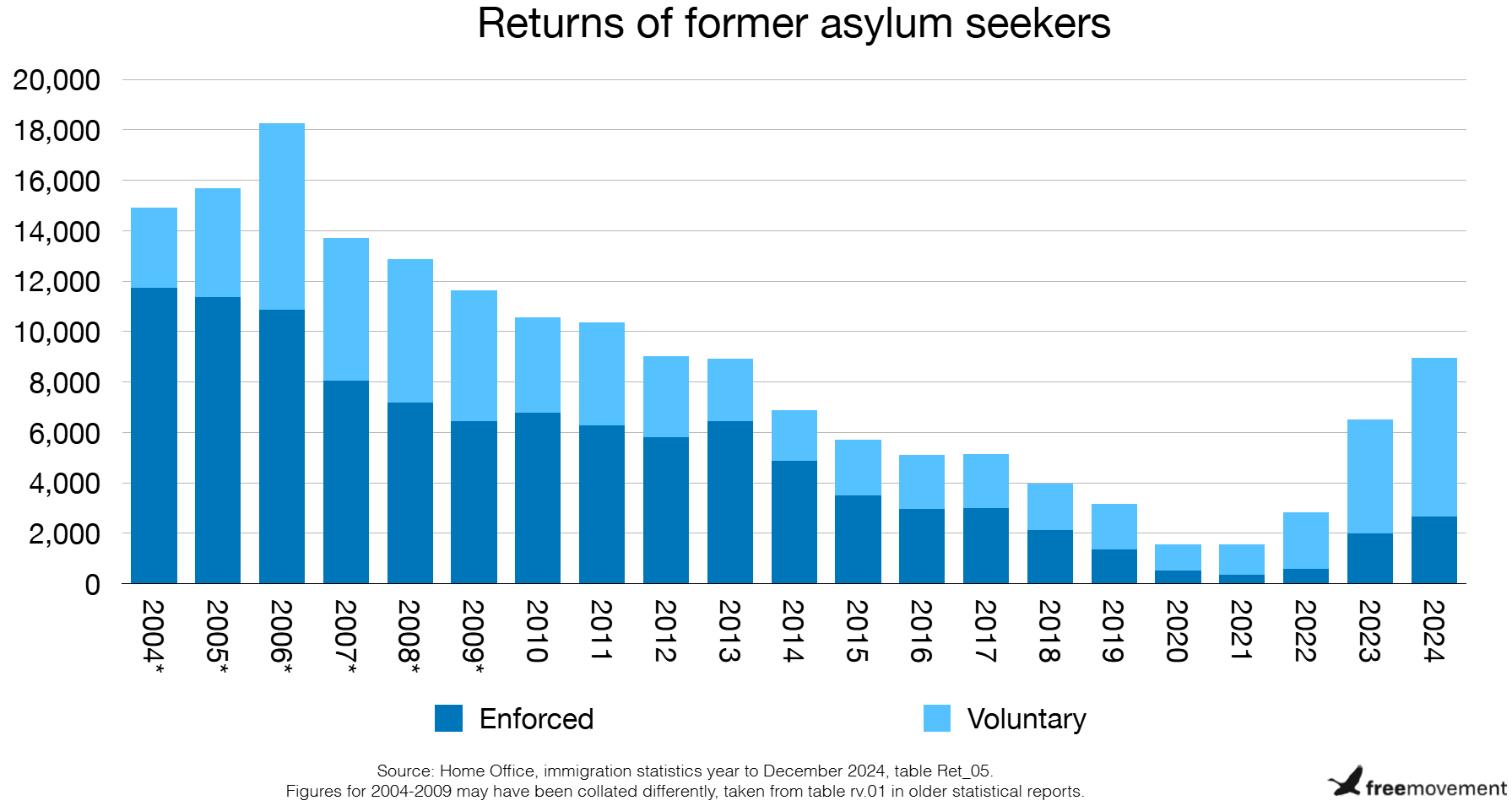

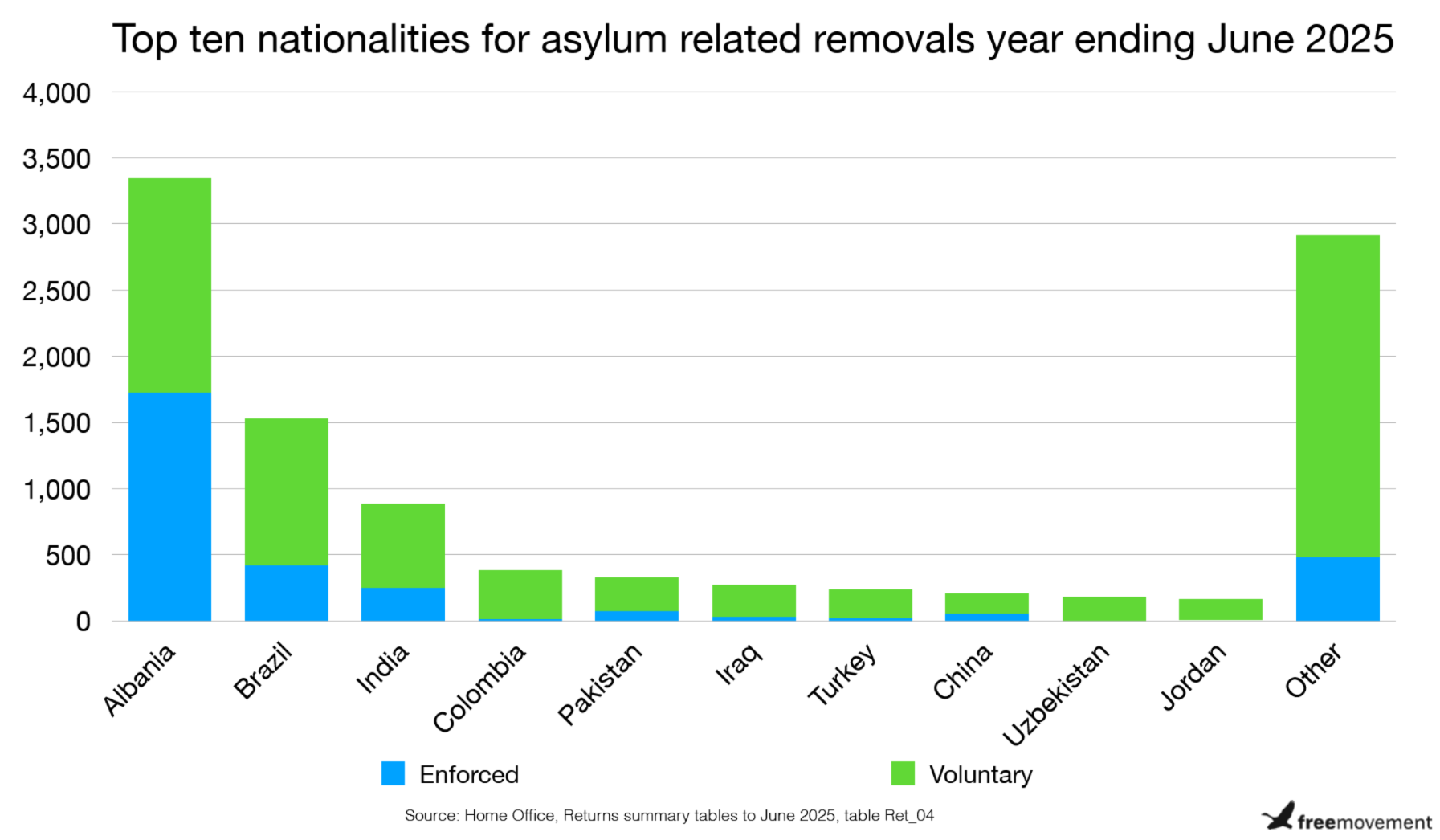

The last three years has seen a reversal of the long term downward trend in removals where very few asylum seekers have been removed or voluntarily departed from the UK. This may be in part because there were fewer failed asylum seekers to remove because of the comparatively low number of claims, the high grant rate and a lower volume of decisions. As decisions increase, so does the number of people whose claims have concluded without success and who now face removal from the UK.

There were just 346 enforced asylum returns in the whole of 2021 and 579 in 2022. The number increased to 1,992 in 2023 and in 2024 there were 2,636 enforced asylum returns.

During 2024 there were a total of 44,433 asylum refusals. Of course, removals are unlikely to occur straightaway following refusal, not least because a refused asylum seeker has a right of appeal. There were 31,698 asylum refusals in 2023.

In total, there have been 96,910 asylum refusals in the last five years (2020 to 2024) and around 24,508 enforced and voluntary asylum-related returns.

The reality is that even those who lose their asylum cases — a relatively small minority at the moment, given the rise in the grant rate — are likely to remain in the United Kingdom in the long term. No government has been willing to engage with this policy issue since 2010.

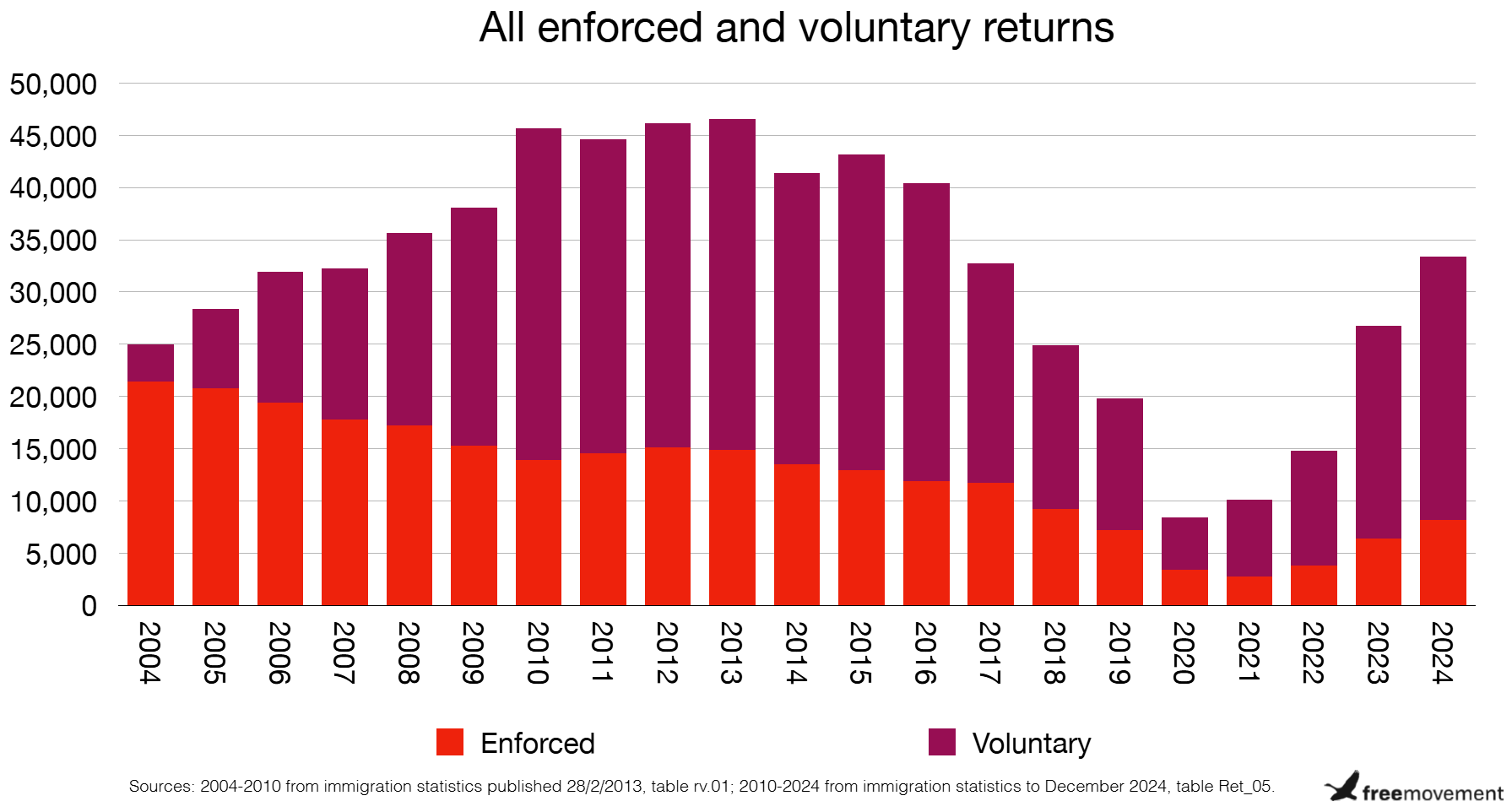

For removals as a whole, we can see the figures steadily increasing after the Covid related drop.

The vast majority of removals relate to people who have never claimed asylum in the UK. In 2024, 32% of enforced removals were asylum related and 25% of voluntary removals were asylum related.

Immigration detention

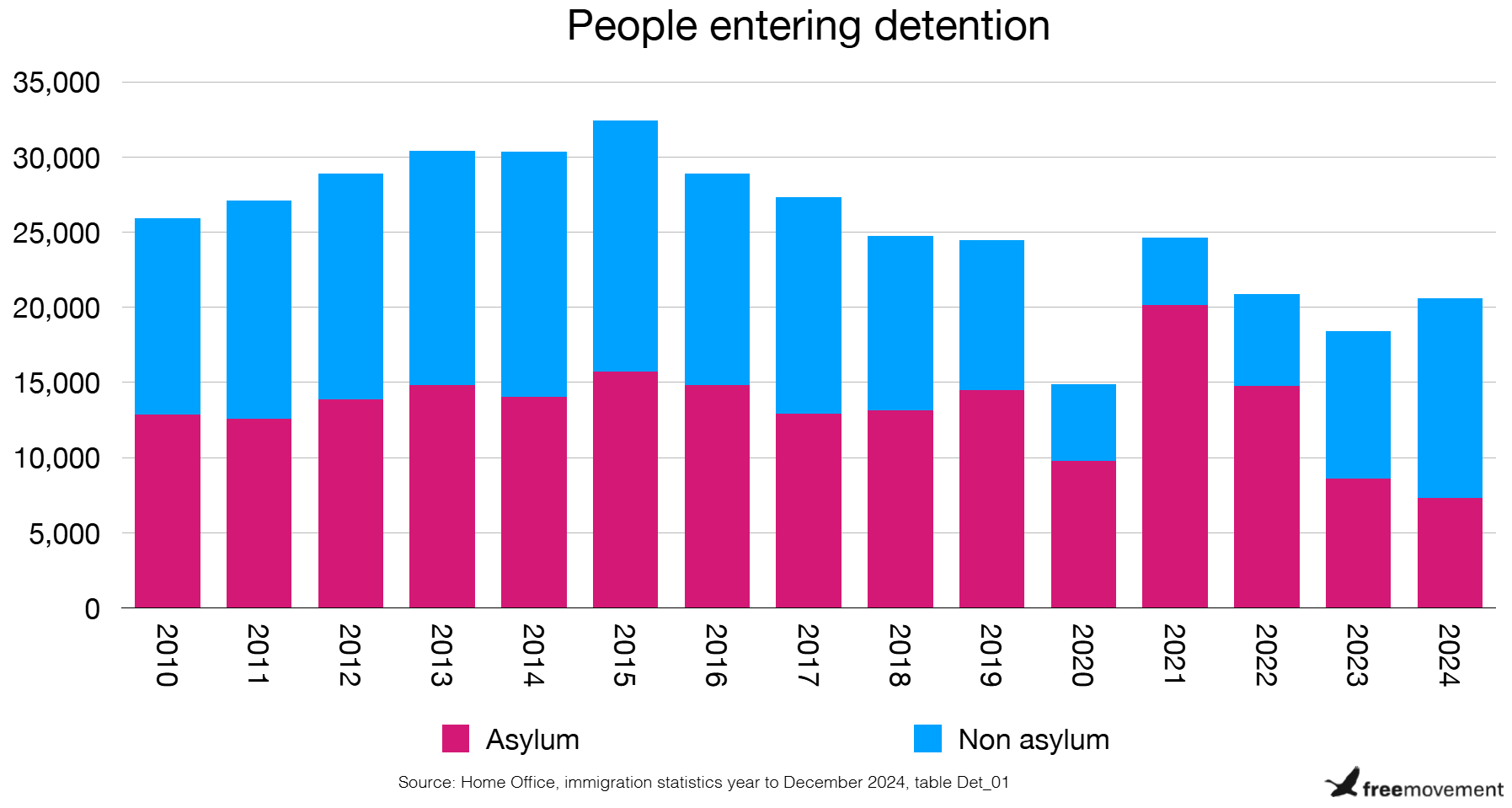

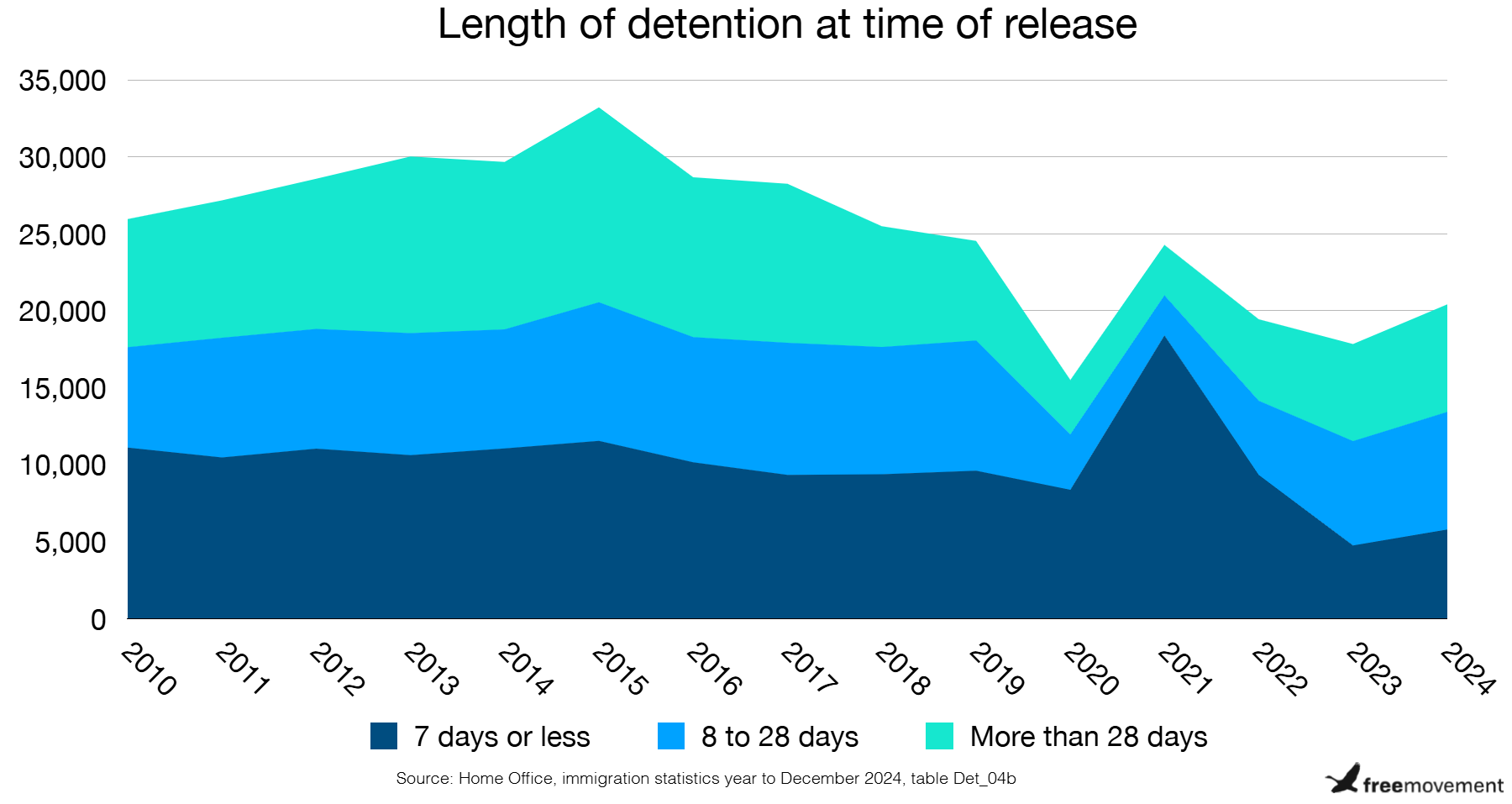

Use of immigration detention has decreased in recent years. At the same time, the percentage of people in the asylum system being held in immigration detention increased markedly in 2021 and 2022 before dropping in 2023 and then increasing again in 2024.

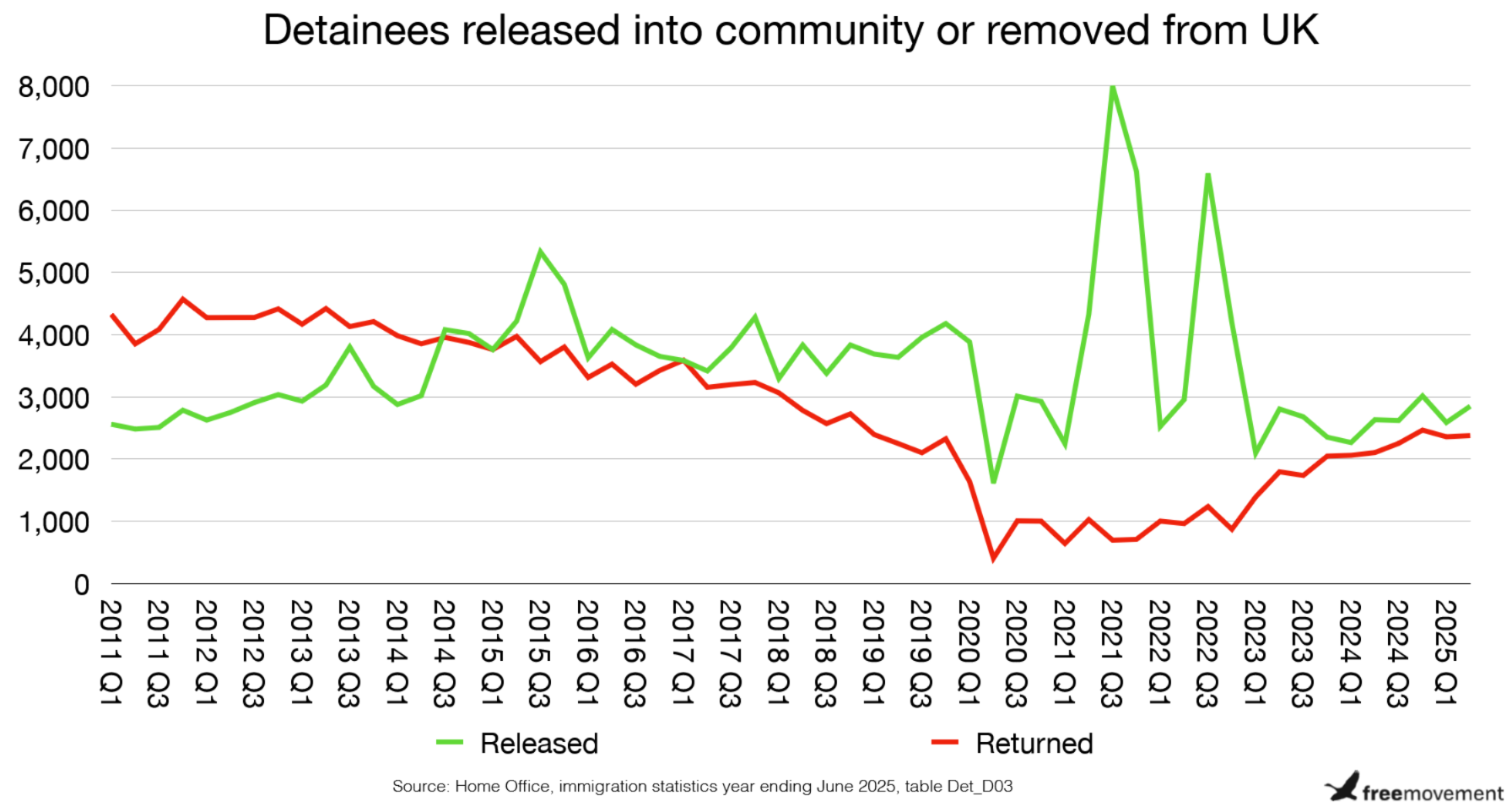

Immigration detention is supposed to be for the purpose of removing those with no permission to remain in the United Kingdom. Immigration detention centres are formally called ‘removal’ centres. However, the number of detainees leaving detention to be removed from the country has fallen drastically since 2010. The majority are released into the community, albeit by a much smaller margin than in recent years.

This calls into question whether a decision to detain these people was the right one. The cost of holding a person in immigration detention was around £133.50 per day for the period April to June 2025.

Substantial numbers of people experience fairly short term detention and some experience prolonged detention.

The capacity of immigration detention is very limited compared to the number of failed asylum seekers, particularly bearing in mind that detention space is also needed for foreign national offenders, overstayers and refused entrants. Unless a government is willing to build extensive (and expensive) prison camps and then also use them — meaning long term detention of some, dawn raids, self harm, suicides other manifestations or consequences of that degree of state coercion, the number of detention spaces is never likely to be sufficient to remove all those the government in theory wishes to remove.

Detention is therefore likely to be arbitrary, in the sense that it is a matter of good or bad luck whether any given individual in the “pool” of potential removees is actually detained and removed. Effectively, all it is being used for is to punish a small sample of a wider class of person.

If detention is to be used on a more rational basis, the issues are around how Home Office resources are organised and allocated, what groups if any are targeted for removal and what safeguards if any are used to prevent discrimination, abuse and the selection of ‘soft’ targets.

For example, detaining for a prolonged period a foreign national offender who is never likely to be removed means that one detention space is “blocked” for a substantial period. Its function is to give the department short term political cover but it comes at the cost of not being able to use that detention space for other purposes. It is obviously bad for the detainee, it is pointless aside from the political cover it provides and it is actively harmful to wider departmental objectives.

The drift in recent years away from the use of detention for the purpose of removal is likely to be the result of a lack of focus on these issues.

Resettlement and safe and legal routes

The government likes to talk about safe and legal routes to reach the United Kingdom. The reality is that unless you are Ukrainian or from Hong Kong there are no such routes to speak of.

There is no queue to jump. It is not possible for a person to apply for the general resettlement scheme. Eligibility is determined by UNHCR. Essentially, a person has to be a registered refugee in a UNHCR administered refugee camp and hope they are picked for resettlement. If they are selected, they have no say over the country to which they are resettled. It might be the UK but it might be Australia, Canada, the United States or other participating countries.

The good news is that as 17 December 2024 a total of 218,600 Ukrainians were in the UK under the two visa routes opened for them. More will have arrived and returned home in that time. Many more visas than that were issued but not yet used. UNHCR have put together data on which countries are hosting how many refugees from Ukraine. By way of comparison, Poland is estimated to be hosting 1,000,320, Germany 1,243,445, Czechia 374,310, Spain 235,680, Italy 170,595, Ireland 115,010, the Republic of Moldova 133,310 and France 70,525.

A total of 166,300 British Nationals (Overseas) from Hong Kong and their dependants have arrived in the UK under the route opened for them in January 2021. While the Home Office has classed this as a resettlement or protection route, the vast majority are not refugees according to the legal definition of a refugee and many reject that label.

What can be done?

The United Kingdom asylum system is indeed broken. It is, to a very significant extent, the Conservative government that broke it. It was on their watch that small boat crossings soared and so did the asylum backlog. Schemes like a new ten year route for refugees, later abandoned, the Rwanda fiasco, the Illegal Migration Act and in particular the use of the inadmissibility process to bring the system almost completely to a halt made the situation worse not better.

However the change in government has so far brought little in the way of good news, apart from ditching the Rwanda plan and use of inadmissibility process – neither of which was ever going to have much of an effect on the issues discussed in this post. But, as we have seen, there are still significant issues that need to be addressed, currently caused in large part by the poor quality of decisions being made by the Home Office and a tribunal backlog exacerbated by the lack of legal aid lawyers.

Without quick action to correct decision making, the backlog in the First-tier Tribunal will only get worse. Instead, we are faced with nonsense like a return to the days of immigration “adjudicators”, while the Home Office continues to pump poor decisions into the tribunal system.

Ministers and managers need to think about prioritising resources. This has to mean doing less of some things in order to do more of others. Why not just grant recognised refugees immediate settlement, for example, rather than conducting a meaningless review of their status after five years?

The asylum system is not beyond repair. It requires competent focus on the boring day job instead of being distracted by pointless or even counterproductive gimmicks. Prioritising the speed of decision making over getting that decision right the first time does very little to fix things.

Similarly, treating claims as withdrawn for spurious reasons is a short term solution addressing only numbers, not people. People who will still have to be supported by the state while getting their claims up and running again, or they will disappear, as without any prospect of being granted asylum there is no incentive to remain in contact with the Home Office.

Recent changes show that positive asylum decisions can be made much, much faster than in the past, which is great news for everyone. It just should not be that hard to grant asylum to people from certain high grant nationalities such as Sudanese where the grant rate is 99%. All officials need to do is to establish nationality, conduct security checks and issue the grant letter.

Instead, we now see the Home Office changing tack and is refusing Afghan asylum claims in huge numbers – 6,066 people in the year ending June 2025. These are now cases which will move to the tribunal where many can expect to succeed. If the Home Office takes the same approach with Syrian cases, where the situation remains unstable and uncertain, then several thousand more of these cases will also move to the tribunal.

Allowing asylum seekers to work after six months waiting for a decision would mean far fewer becoming homeless when they are granted asylum, for example. Permanently giving them a bit more time between receiving their immigration papers and evicting them might reduce the number who end up homeless. A support and welcome package for newly recognised refugees should be introduced, which would save money in the long run.

More resources urgently need to be challenged into asylum appeals and legal aid. The appeal success rate remains high, suggesting that many appeals are being lodged that would not have been necessary if the initial decision had been properly made.

Proper, realistic reviews of pending cases by the Home Office, particularly in light of the known issues around quality, might reduce the appeals backlog and save considerable time and money. Monitoring of officials who wrongly refuse applications or reject an appeal review should be introduced.

The department’s approach to detention and removal needs reviewing. What is detention really for? If very few failed asylum seekers can be removed then does the department want to focus resources on particular groups and what should happen to the rest? Is it acceptable to simply add them to the unauthorised resident population and allow people to regularise only after they have children or live below the radar for 20 years?

If we step back and look at the fundamental change in the asylum grant rate combined with the low number of asylum removals and departures, we can see that it is time to scrap the deterrent policies established in the 1990s and early 2000s, when far fewer asylum claims succeeded. Michael Howard, then Home Secretary, told Parliament in 1995 that only 4% of asylum succeeded as did a further 4% of appeals.

The ban on the right to work, the destitution-level support offered instead, the squalid accommodation and camps and the highly bureaucratic, faceless asylum process all absorb vast Home Office resources to administer. These policies, which belong to a bygone age, deter no-one. They merely serve to punish genuine refugees who will ultimately get to stay in the United Kingdom in the long term. It is their interests and ours to help them integrate as soon as possible rather than forcing them into this demeaning purgatory first.

This article was updated by Sonia Lenegan in August 2025 with the most recently published statistics.

SHARE

5 responses