- BY Sonia Lenegan

What safe and legal routes are available for refugees to come to the United Kingdom?

Table of Contents

ToggleThe mantra of “safe and legal routes” is regularly repeated by the government when justifying increasingly draconian legislation in an attempt to prevent refugees from travelling to the UK under their own steam. The argument is that refugees should use these safe and legal routes instead of arriving in small boats or the back of lorries to claim asylum.

In this article we look at what safe and legal routes are available, how they are accessed, and the grant of leave and entitlements of those who are successful. We have also taken a look at asylum applications made over the same period of time, so that the impact of these bespoke routes on arrivals can be considered.

Unless indicated otherwise, figures come from the Home Office statistics for the year ending March 2025. We have focussed on the period 2020 to the end of March 2025, as it is during this period that most of the bespoke schemes that are currently open were set up.

UNHCR resettlement schemes

There are three different general resettlement schemes operated in partnership between the UN refugee agency (UNHCR) and the UK government: the UK resettlement scheme (or UKRS), the community sponsorship scheme and the mandate resettlement scheme. All three depend on UNHCR to identify those eligible. Full details are set out in the UK Refugee Resettlement policy guidance.

No application can be made for resettlement under the first two of these three schemes. UNHCR is explicit about this fact. A person just has to wait and hope they will somehow be picked. Even if they are picked, they have no say about the country in which they will be offered resettlement. And, to put things in context, less than 1% of the world’s refugees are submitted by UNHCR to partner countries for resettlement every year.

Under the UK resettlement scheme, UNHCR identifies and interviews people with potential resettlement needs, decides whether they are a refugee and will refer them to the UK where they meet the criteria for resettlement as set out in UNHCR’s resettlement handbook. The scheme can include unaccompanied children.

The current status of this scheme is unclear, as it appeared from a parliamentary debate in 2023 that it was closed to new referrals. In another debate on 27 March 2025 the government said that it was yet to agree a quota for the route in 2025.

The community sponsorship scheme operates in tandem with the UK resettlement scheme. It provides for families arriving in the UK to receive support from community groups, including the provision of housing for a minimum of two years, and support with accessing services such as English language lessons, NHS, social services, cultural orientation, and support towards employment and self-sufficiency. Consent must be obtained from the local authority before the application is submitted to the Home Office.

Once the community sponsor is ready and is matched to a family, they need to jointly agree on the family’s arrival with the local authority. The family will usually arrive six to 12 weeks after that. The family is identified by UNHCR, following the same processes as for the UK resettlement scheme.

The Home Office provides funding to Reset, an organisation that helps community groups to participate in the scheme. Certain requirements need to be met to be a community sponsor, which is usually a registered charity or community interest company, or a church group.

The third scheme, the ‘mandate’ one, is only available to people who UNHCR has recognised as refugees and identified as being in need of resettlement. This scheme is for people who have a close relative in the UK, who must be settled in the UK or have limited leave to remain in a route that leads to settlement, and who are willing to accommodate and support the refugee. The refugee must be the minor child, spouse, or parent or grandparent aged over 65 of the UK based relative. Exceptional circumstances are required for other family members to benefit from the scheme.

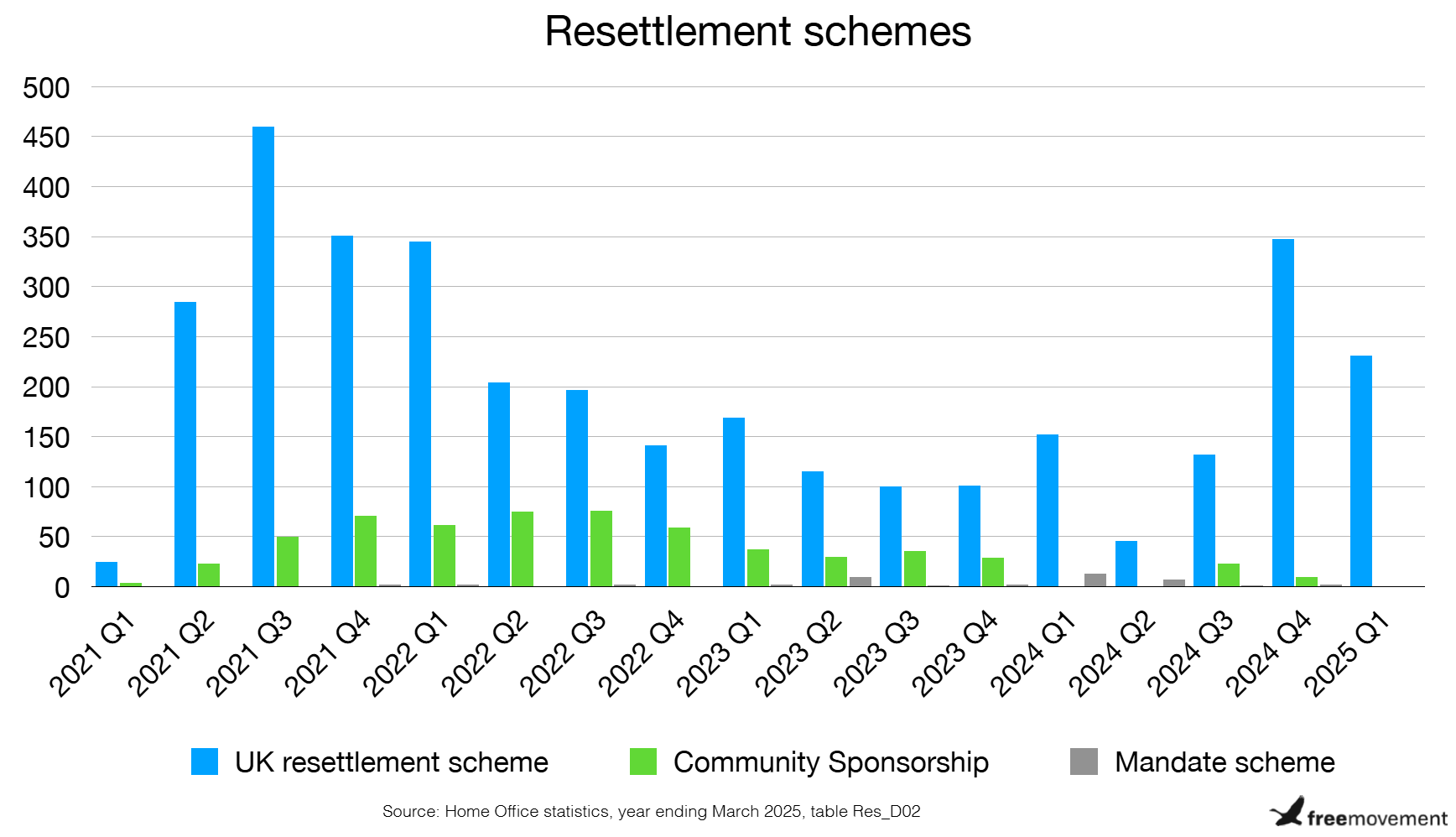

Grants under the mandate scheme are negligible, with only five in 2020, two in 2021, four in 2022, 15 in 2023 and 23 in 2024. As can be seen from the below, the majority of grants are under the UK resettlement scheme. As of the March 2025 data, the Home Office has stopped reporting the community sponsorship figures separately and has instead rolled these into the UK resettlement figures. In comparison to the other resettlement schemes we’ll look at here, we can see that the numbers are relatively low.

Once accepted by the UK, people are granted six months’ leave outside the rules to enable their entry and are then granted indefinite leave to remain and refugee status on arrival here. Refugee family reunion is available to this group to bring eligible family members over to join them under Appendix Family Reunion (Protection).

Refugee family reunion

Where a person has refugee status and has not naturalised as a British citizen, they are entitled to bring their partner and children to the UK where they meet the requirements. Family reunion applications can be made under Appendix Family Reunion (Protection) of the immigration rules.

There is no provision in the rules for children to apply to bring their family members to the UK. Where the rules cannot be met, applications can also be made on the grounds of exceptional circumstances under paragraph FRP 7.1. These applications are considerably more difficult and can be dangerous for the person concerned.

Our article Top tips for making refugee family reunion applications outside the normal rules is essential reading for anyone making these applications.

Family reunion is a crucial route for refugees to be able to reunite with their families. However, the applications can be overly complex and difficult to navigate without a legal aid lawyer with the capacity and expertise required.

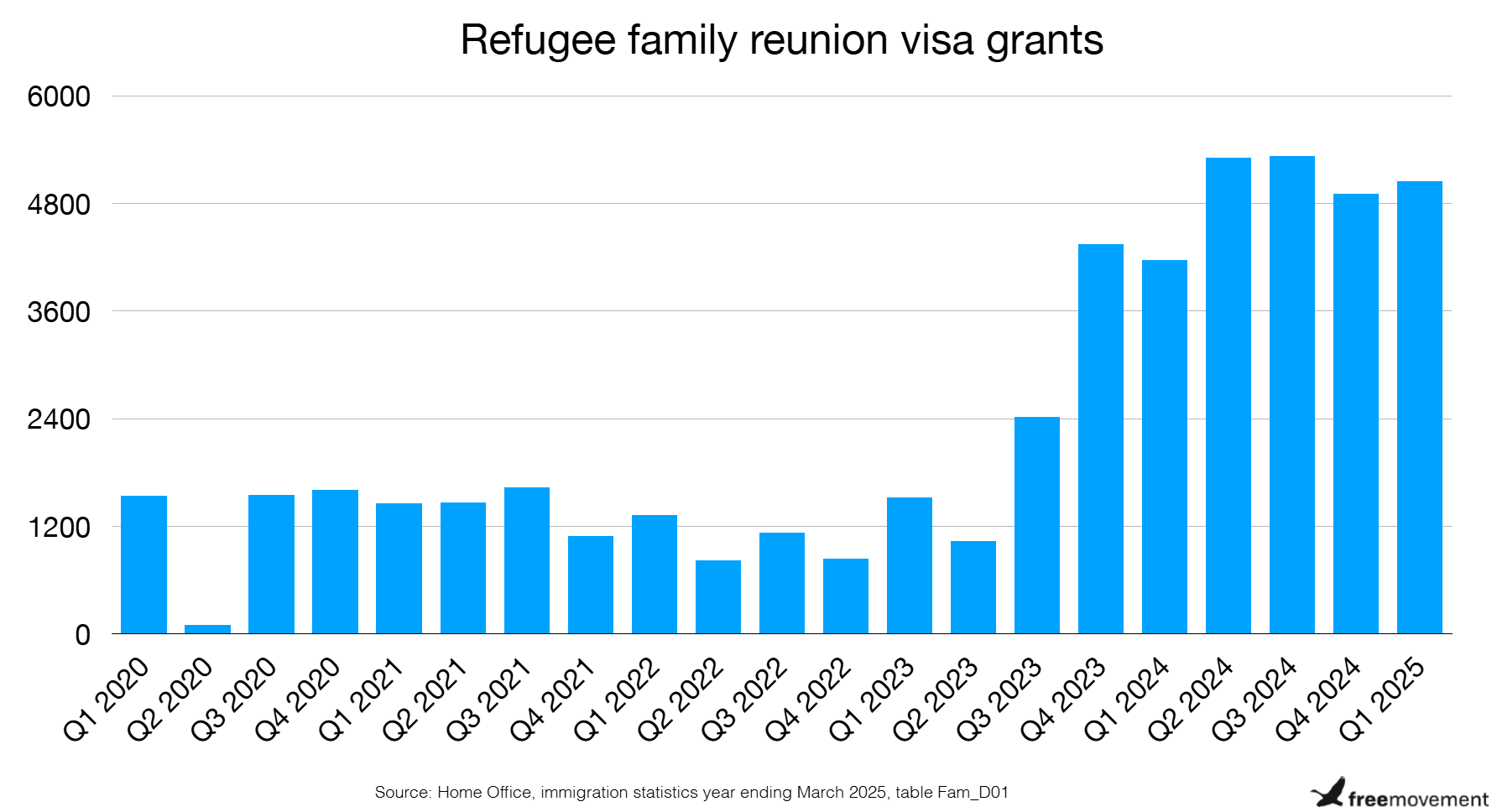

Getting data from the Home Office on family reunion applications can be difficult, with FOI requests on case handling routinely being refused. A more recent request on grant rates was successful and shows that in 2019 the grant rate was 73.5%, in 2020 72.5%, in 2021 71.3%, 2022 was 74.4% and there was an increase to 86.3% in 2023.

Refugee and Migrant Forum of Essex and London (RAMFEL) has previously obtained FOI data showing that 1,386 (66%) of family reunion applications that were rejected by the Home Office were allowed on appeal between 2019 and 2022.

Those entering under the refugee family reunion rules are not formally recognised as refugees. Successful applicants are granted leave that expires at the same time as their refugee relative, but do not receive refugee status.

Hong Kong

This is a good example of where the bespoke routes can be problematic, as the recent immigration white paper has caused a great amount of concern that this route could have its path to settlement doubled from five to ten years. The government has done nothing to allay these fears. If the change is made, then anyone who came to the UK under this route would have been better off claiming asylum on arrival and obtaining refugee status (if eligible), which undermines the use of these routes as an alternative to claiming asylum in the UK.

The background to the introduction of the route is that China’s parliament passed a draconian new National Security Law for Hong Kong, bypassing Hong Kong’s own Legislative Council, on 30 June 2020. In response, the UK government announced the Hong Kong British National (Overseas) Visa on 22 July 2020, and Appendix Hong Kong British National (Overseas) was later introduced effective from 31 January 2021.

There are two separate routes, BN(O) Status Holder and BN(O) Household Member. The second of these is for adult children and their dependants, who formed part of the same household as a BN(O) Status Holder. BN(O) Status Holders can bring a dependent partner and children, and other family members with a “high level of dependency”.

This is the only one of these bespoke routes which has an application fee, which is £193 if applying for two and a half years, and £268 if applying for five years. The immigration health surcharge must also be paid. For adults this is currently £2,587.50 for two and a half years and £5,175 for five years.

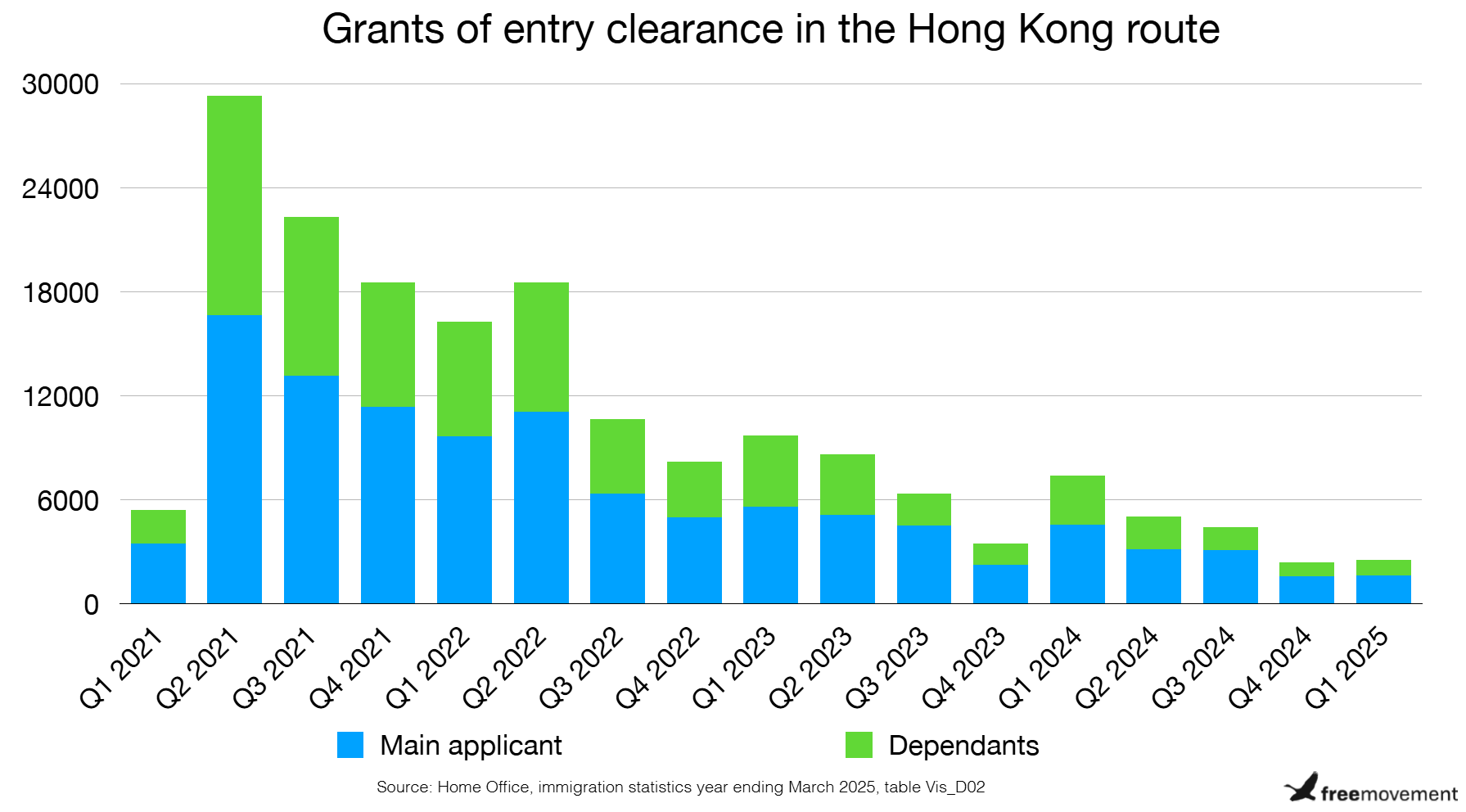

As can be seen below, the number of grants has dropped significantly over time. The scheme has been operating for over four years and the majority of people who are eligible and wish to come to the UK are likely to have already done so.

Those granted leave under this route can currently apply for indefinite leave after five years’ continuous residence in the UK (including that acquired prior to the grant of leave in this route). Initially this grant of leave was subject to the no recourse to public funds condition with no ability to ask for that to be lifted, however this was later amended so that people with this type of leave are now permitted to apply to have the condition lifted.

The BNO route is available to and has been used by people with a large variety of nationalities, including Australia, India, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, Australia, Malaysia, Morocco, Nepal, Pakistan, Portugal, Russia, Taiwan, Vanuatu, Angola, Burma, Canada and Yemen (source: table Data_Vis_D02). It is therefore difficult to assess the impact of this route as an alternative to irregular arrivals.

Only 66 Hong Kong nationals have been granted refugee or humanitarian protection status from the second quarter of 2020 to the end of March 2025. Delays may account for some of this low number, but it seems likely that some people will have withdrawn their claims after the BNO route was opened.

Afghanistan

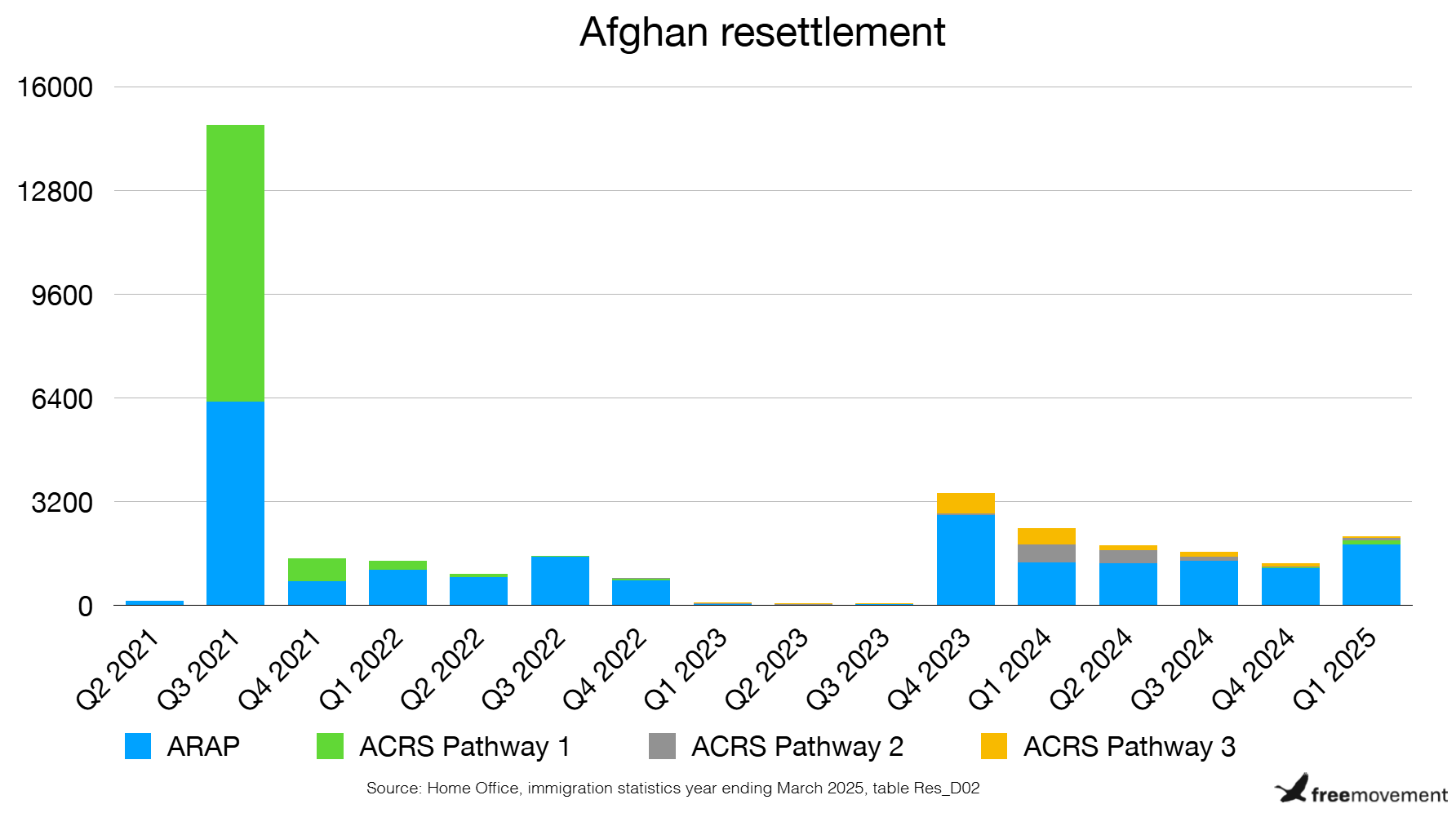

The Taliban regained control of Afghanistan in August 2021 and the UK evacuated around 15,000 people to safety under Operation Pitting. Two routes were announced to help Afghan refugees: the Afghan Citizens Resettlement Scheme (ACRS) and the Afghan Relocation and Assistance Policy (ARAP).

It is not possible to apply under the Afghan Citizens Resettlement Scheme. The scheme is split into three Pathways, the first of which was filled before it opened, with those who had been evacuated under Operation Pitting. Pathway 2 is only for cases that are referred to the UK by UNHCR, as for the general resettlement schemes detailed above.

Pathway 3 initially had 1,500 places available, which was to include family members, and the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office accepted expressions of interest from British Council contractors, GardaWorld contractors and Chevening alumni. This cap was later removed and the scheme closed to new expressions of interest in October 2023. Decision making on eligibility for the route was completed on 28 June 2024.

It is possible to apply under ARAP. In order to access the ARAP scheme, a person must first apply for an “eligibility assessment” that is carried out by the Ministry of Defence. The form expressly states that it is not an application for leave, including for leave outside the rules.

Once deemed eligible, the Ministry of Defence makes the application to the Home Office on behalf of the applicant. The relevant immigration rules are Appendix Afghan Relocation and Assistance Policy (ARAP). The criteria for ARAP were narrowed considerably in December 2021.

Family members must be included in the initial eligibility application, and applicants can bring a partner, their children, and an additional family member.

Both schemes have triggered a very considerable amount of litigation as a result of their inaccessibility and strict criteria:

- Afghan evacuation litigation latest

- Afghan interpreter successfully challenges entry clearance refusal

- Afghan Scheme does not stray from original policy intention by restricting eligibility

- Successful challenge in the High Court helps family of Afghan judge

- Court finds Afghan resettlement decision was made contrary to policy and without adequate reasons

- Afghan judge wins judicial review of refusal of leave

- No visa for Afghan interpreter accused of leaking sensitive information

- High Court finds no legitimate expectation of equal treatment in Afghanistan evacuation case

- High Court quashes decision to refuse leave to Afghan journalists

- Former Afghan Supreme Court judge succeeds in challenge to resettlement refusal decision

- Yet another Afghan judge successfully challenges exclusion from resettlement scheme

- Procedural fairness requires reasons to be given in Afghan resettlement refusals

- Afghan family to have application decided a sixth time after unfair refusal

Those who are successful were granted six months’ leave outside the rules, and then indefinite leave to remain after arrival in the UK (eventually). They were not granted refugee status, which limits their ability to access family reunion. In contrast to the Homes for Ukraine scheme, Afghans were put into hotels, many of them left there for lengthy periods.

Given the fact that both schemes effectively filled their first year’s quota with people evacuated from Afghanistan under Operation Pitting, there have been only low numbers of grants since then. It was also disclosed in a report by the Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration that the government secretly paused processing entry clearance applications made under ARAP which presumably explains the very low figures for the first three quarters of 2023. Since then grants have started again.

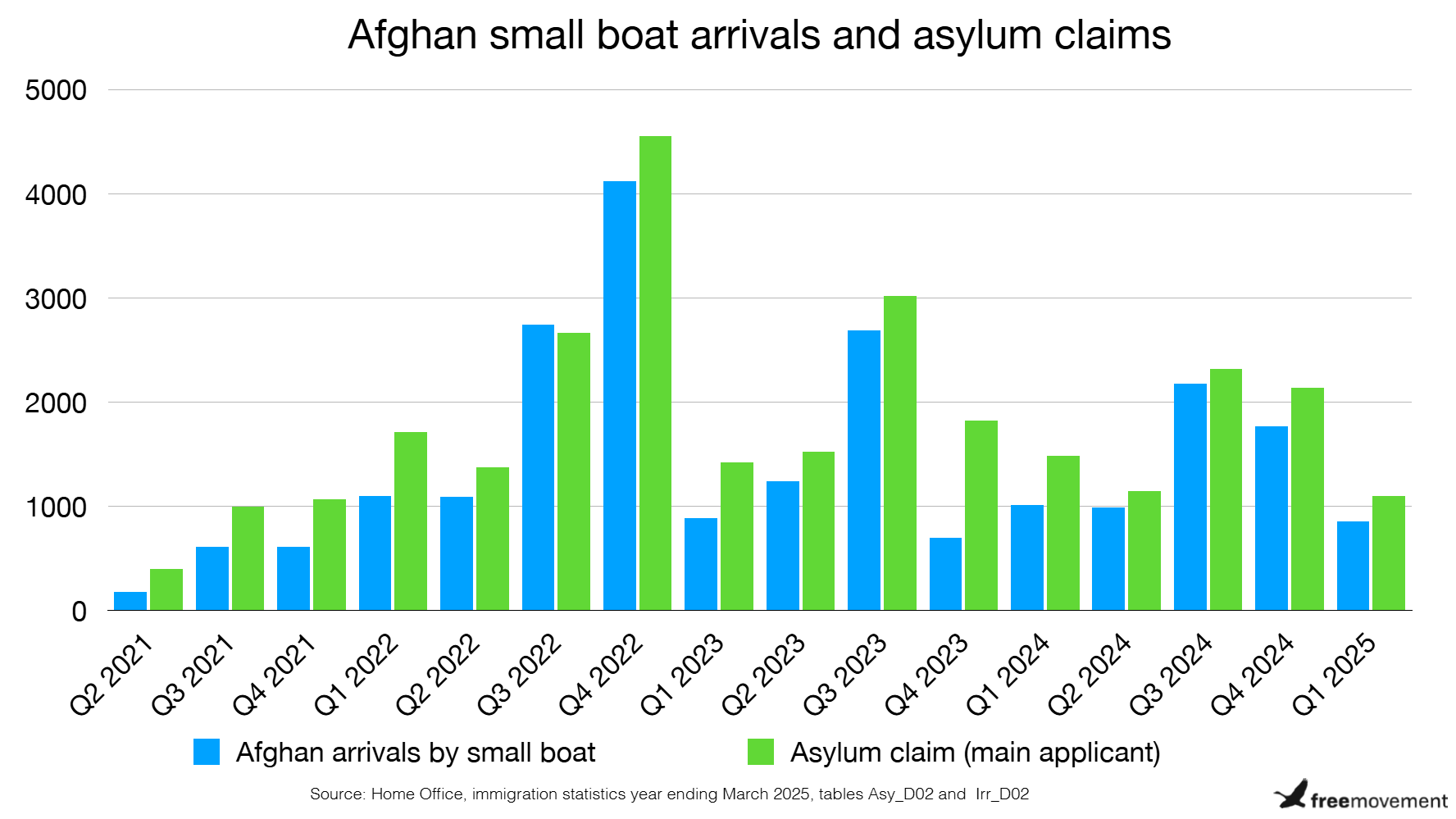

Given the difficulty and delays in accessing the existing schemes, it is unsurprising to see a large number of people arriving via the Channel and claiming asylum.

It is unclear how many of those people making that journey would have been eligible under other other routes, but some do so because they have family in the UK but are unable to reunite with them under existing schemes.

Ukraine

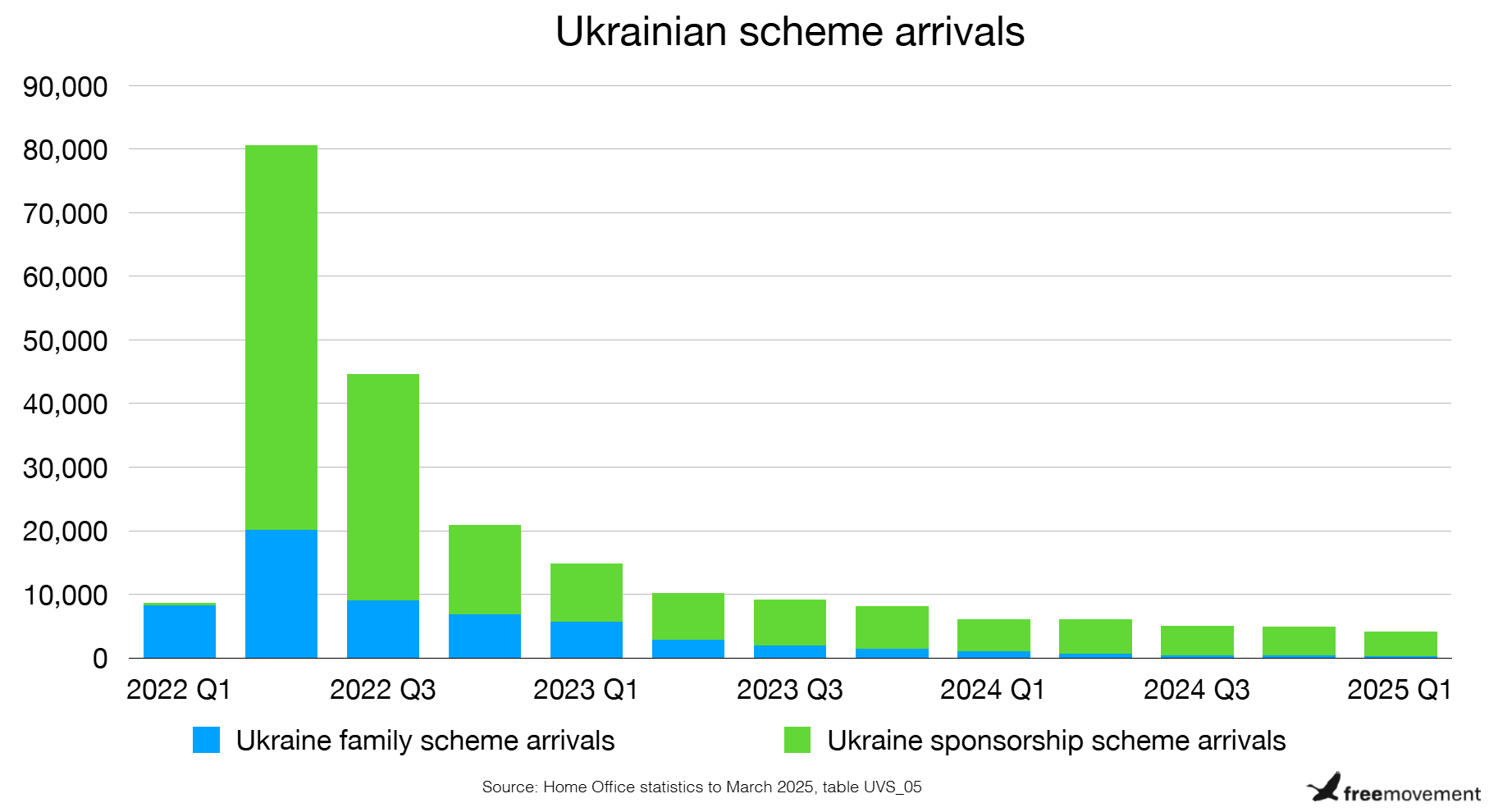

The first of the UK’s three schemes to help those displaced by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was the Ukraine Family Scheme, introduced on 4 March 2022, just over a week after the invasion. The Ukraine Sponsorship Scheme (better known as ‘Homes for Ukraine’) was introduced on 18 March 2022. A third scheme was later introduced for people who were already in the UK, and so that will not be covered here.

The relevant immigration rules are set out in Appendix Ukraine Scheme. Until it was closed without notice on 19 February 2024, the Ukraine Family Scheme allowed a vastly wider group of family members to be brought than under any other provision of the immigration rules or resettlement scheme. This included grandparents, grandchildren, siblings, cousins, aunts and uncles.

Successful applicants under the Ukraine schemes were initially granted three years’ leave to remain, this was reduced to 18 months under the remaining Home for Ukraine scheme on 19 February 2024. There is no path to settlement and leave under Appendix Ukraine is expressly excluded from the long residence route, meaning that this is another “bespoke” route where people may well have been better off with an asylum claim. In February 2025 the Ukraine Permission Extension Scheme opened, allowing people to make a free application for a further 18 months’ leave.

At the moment the scheme looks successful due to the numbers arrived, but it has not been without its problems, both during set up and since.

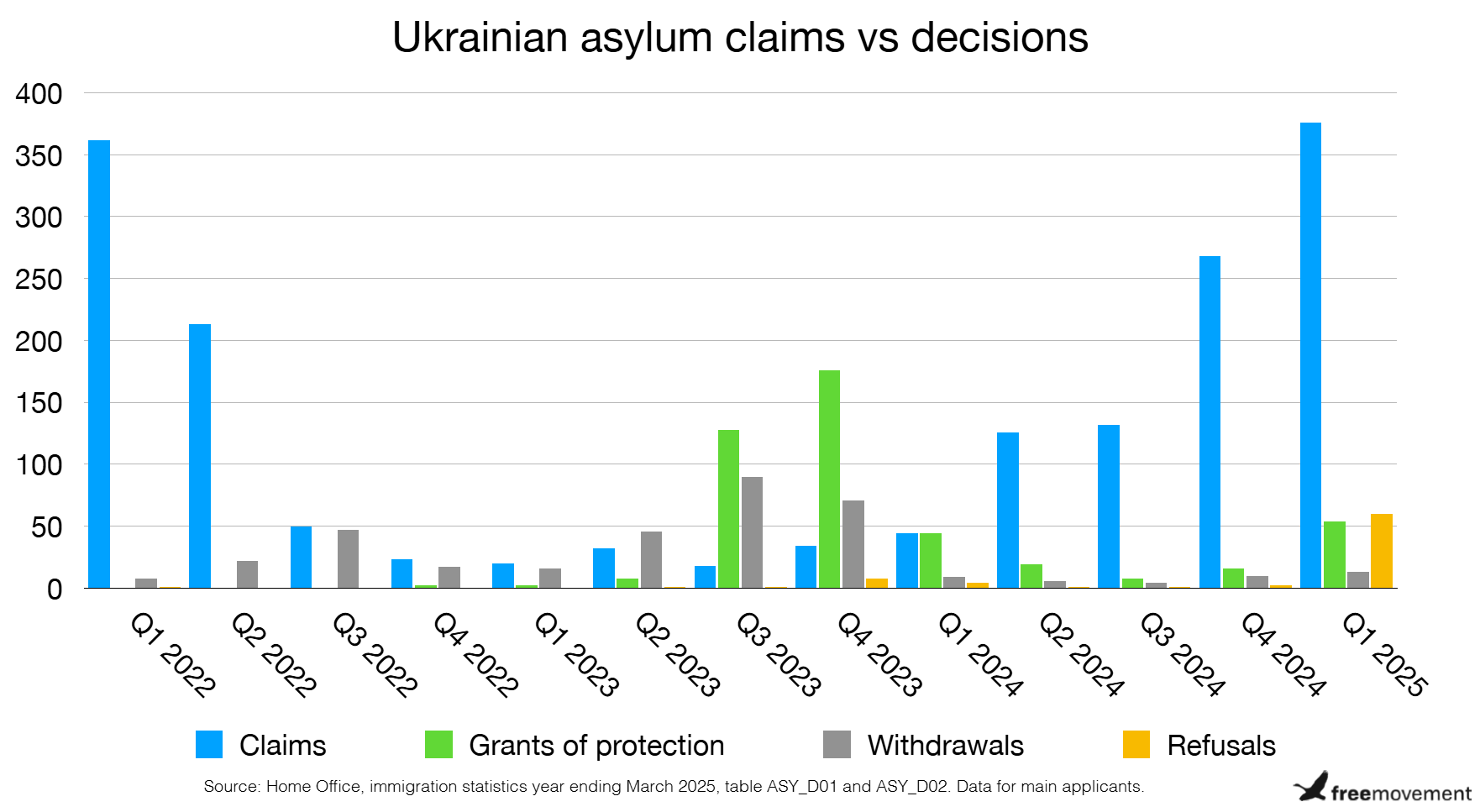

The question of what happens to Ukrainians in the longer term remains unclear. Perhaps motivated by this, some Ukrainians have claimed asylum in the UK, which would provide a five year grant of leave and a path to settlement if successful.

From the beginning of 2022 until the end of March 2025 there have been 1,698 asylum claims made by Ukrainian nationals (as the main applicant, the figure including dependants is higher). 902 of those claims were made in the 12 month period ending March 2025.

Since the beginning of 2022 there have been 457 grants of asylum or humanitarian protection to main applicants, 304 of those were made in the second half of 2023. From the beginning of 2022 to the end of 2024 there were 19 refusals of Ukrainian asylum claims. In the first three months of this year there have been 60 refusals. This seems to have been prompted by a change in the country guidance in January this year, which I intend to look more at and write up in more detail shortly.

Seven Ukrainians are recorded as having entered the UK by travelling across the Channel in a small boat, four of those in the third quarter of 2024 (source: table Irr_D01).

Scheme comparison table

| Length of leave granted? | How long until settlement? | Refugee status? | Application process? | Refugee family reunion available? |

UK Resettlement | Six months LOTR | ILR granted on arrival | Yes | No | Yes |

Family reunion | In line with refugee sponsor | In line with refugee sponsor | No | Yes | No |

Hong Kong | 2.5 or 5 years | After continuous residence in the UK of five years | No | Yes (£) | No but can apply to bring dependants |

ARAP | Six months LOTR | ILR granted on arrival | No | Can submit a request for eligibility assessment | No |

ACRS | Six months LOTR | ILR granted on arrival | No | No | No |

Homes for Ukraine | 18 months | N/A, settlement is not available | No | Yes | No but can apply to bring in dependants |

Conclusion

Considerable numbers of refugees and people in need of protection have benefited from the UK’s resettlement schemes over the last few years. But there are issues with this “bespoke” approach, not least the difficulty in setting them up as quickly as is needed and the lack of transparency around how people can access some of the schemes.

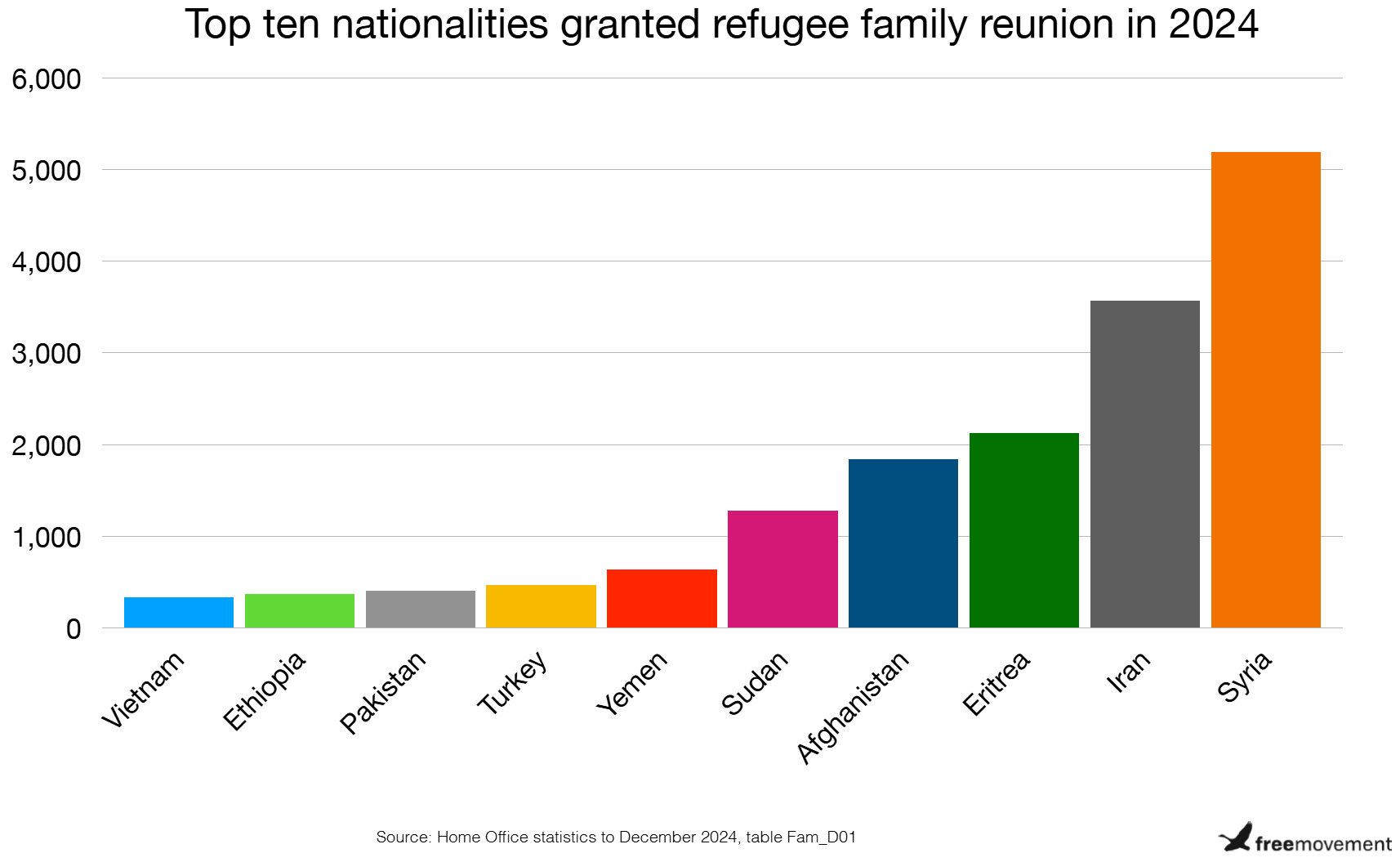

Overwhelmingly, those who have been able to access protection have been from Ukraine and Hong Kong and, for a brief moment in 2021, from Afghanistan. Notable recent examples of where safe routes are needed but have not been provided include Uganda (in respect of LGBTQI+ people), Sudan and Gaza.

For these people, there are no “safe and legal” routes for them to come to the UK. We will continue to see people making their own way here in order to seek safety, regardless of the government’s attempts to legislate a stop to these journeys.

SHARE