- BY George Peretz

The row over post-Brexit visas for musicians, explained

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Table of Contents

ToggleFurious musicians have gathered over 260,000 signatures on a petition to the British government asking for a “Europe-wide visa-free work permit for touring professionals and artists”. In response, the government claims that “during our negotiations, we proposed measures to allow creative professionals to travel and perform in both the UK and EU, without needing work-permits. Unfortunately, the EU rejected these proposals”. EU sources retort that the offer had come from its side, and was rejected by the current UK government. So what’s going on, and what is the visa situation for touring musicians when there are no relevant provisions covering them in the post-Brexit trade agreement?

The visa situation for musicians as things stand

One preliminary point to get out of the way – under the Common Travel Area, there are no restrictions on the ability of Irish musicians to play in the UK or on UK musicians travelling to play in Ireland. So in all that follows, “EU” means “EU except Ireland”.

The issue here is paid work. EU musicians travelling to the UK to sing or play at, for example, a charity event for free can do so as visitors to the UK without a visa. The position for UK musicians travelling to the EU is more complicated (as we shall see) but it is almost certainly the case that no EU country will restrict their ability to play for free as a visitor under the usual visa-free Schengen travel arrangements applicable to third country nationals (including, now, UK nationals) – i.e. no visa is required for travel of up to 90 days in any period of 180 days.

The position for paid gigs is more complicated.

For EU musicians visiting the UK, this article is a useful summary. In essence, the UK permits foreign (including EU) nationals to stay up to 30 days to carry out paid engagements, but they must:

- prove they are a professional musician, and

- be invited by an established UK business.

Either condition could be tricky for a young musician starting out and wanting to play gigs. And 30 days isn’t long enough for a part in a show with a run.

Longer stays require a “T5” temporary work visa. This generally requires you to be in a shortage occupation (at the moment the only musicians that qualify are certain orchestral positions) or to have an established international reputation. EU national musicians who are staying for three months or less do not have to apply for this visa in advance, although they must still provide a border officer with the correct paperwork.

For UK musicians visiting the EU, it all depends where you are going. Without an EU-wide commitment as part of the Trade and Cooperation deal, there are 26 different sets of rules. As the Association of British Orchestras puts it:

While some EU countries apply an exemption from work permit rules for cultural activity, along the lines of the UK’s Permitted Paid Engagement, not all do, and it is fair to say that this will make multi-country touring significantly more complicated and expensive.

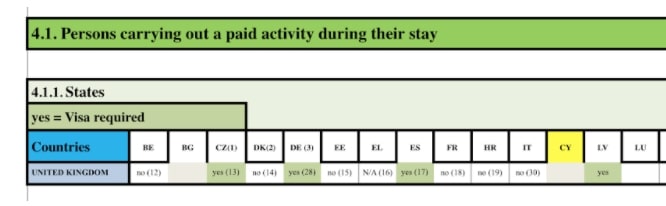

The European Commission has provided a spreadsheet with its analysis of which EU countries require work permits for gigging musicians and which don’t. One glance makes obvious the attractions of an EU-wide arrangement (and the blanks and footnotes suggest that anyone really wanting certainty will need good legal advice from the country concerned).

What was on the table?

Since no one outside the negotiating teams and their respective authorities was in the negotiating room or has seen the precise texts that were put forward in the secrecy of that room, and since neither side can be assumed to be free from spin, one has to apply some caution to what both sides say about their positions save where backed up with publicly-available texts.

The UK position

The current UK government tells us that the EU rejected its offer under which “musicians, artists, entertainers and support staff would have been captured through the list of permitted activities for short-term business visitors”. The terms of that offer have not been made public, but this appears to be a reference to what finally became Annex SERVIN-3 to the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (at page 749) which contains a list of things that short-term business visitors from the EU and UK can do in each other’s territory (with country-specific qualifications). These range from (a) meetings and consultations down to (k) translation and interpretation – but do not include music or other creative or artistic activity.

In order to be covered by Annex SERVIN-3, a UK short term business visitor must not “on their own behalf, receive remuneration from within the [EU]”. Annex SERVIN-3 could, therefore, cover a touring orchestra or band where the musicians are paid by a UK company which in turn is paid by a concert venue within the EU: but it would not cover an self-employed opera singer looking for a part in a Munich opera house or wanting to perform in a concert in Barcelona or a self-employed guitarist looking to play in some bars in Spain, because they would be paid “on their own behalf”.

That reflects the fact that the overall purpose of this provision is not to assist individuals but employers. It allows businesses to send staff over to the other party for “fly-in fly-out” work of various kinds (to negotiate contracts, to meet customers and so on), as well as to move senior employees around between offices in, say, London and Berlin (it also covers “intra-corporate transferees”).

A clue to what might have been the UK government’s approach lies in Article 11.11.1(b) of the UK’s proposed text, published in May 2020. That draft provision allows for a carve-out from the definition of “on their own behalf”: the terms of that carve-out are not public, since the provision refers to an annex that is left blank in the text.

Otherwise, in order to cover self-employed musicians or musicians seeking short-term employment, an addition would have had also to be made to Annex SERVIN-4 at page 755. That Annex does cover “independent professionals” – a term that covers people doing business and getting paid on their own account. However, even if the list of activities covered by that Annex (which currently include such things as legal services, market research, and various other advisory services) had been extended to cover music and creative activity, Article SERVIN 4.1.5(c)(iii) on page 88 makes it clear that an “independent professional” must have both six years experience in the activity in question and relevant university-level qualifications. Some musicians could satisfy those criteria but many do not.

It is therefore somewhat unclear that the UK offer would have helped self-employed musicians, or musicians seeking short-term employment, at all (it certainly would not have done had it extended only to “short term business visitors” as defined in the final text, though it might have done had the unspecified UK carve-out from that definition been adopted). And even if the UK offer had extended to including music among the activities of “independent professionals” in Annex SERVIN-4, many self-employed musicians would not have met the criteria to benefit from such a provision. And, finally, both Annexes SERVIN-3 and SERVIN-4 are subject to a whole host of “reservations” (listed at length in both annexes) that are a minefield for anyone seeking to rely on them.

The EU offer

As to the EU’s offer, that is much clearer as it is made in the draft agreement published in March 2020.

One section of that document covered “mobility”, including the following at page 171:

Article MOBI.4: Visa-free travel

1. The Parties shall provide for reciprocal visa-free travel for citizens of the Union and citizens of the United Kingdom when travelling to the territory of the other party for short stays of a maximum duration as defined in the Parties’ domestic legislation, which shall be at least 90 days in any 180-day period.

2. Member States may individually decide to impose a visa requirement on citizens of the United Kingdom carrying out a paid activity during their short-term visit…

For that category of persons, the United Kingdom may decide to impose a visa requirement on the citizens of each Member State individually, in accordance with its domestic legislation.

What that would have done is set out a baseline position where EU and UK citizens could have done any paid work, without a visa, in each other’s territories for up to 90 days in any 180 days. Music was covered along with everything else (for example, a short term bar or tourist rep job in Ibiza or Chamonix).

From that starting point, any EU state could have imposed a visa requirement on UK citizens carrying out a paid activity, in which case the UK could have reciprocated for that state’s nationals. However, that right would have been qualified, in the case of music, by a proposed Joint Declaration (at page 354 of the text) that would have prevented “artists performing an activity on an ad-hoc basis” from being counted as “paid activity”. Musicians would therefore have been protected against any withdrawal of the right to perform (and to be paid to perform) without a visa at one-off events (gigs or recitals) during a 90-day stay – though longer contracts might have been made subject to a visa requirement.

One can see that the EU’s proposal was lopsided: the UK could only impose visas on, say, Belgian citizens for work of a certain type if Belgium did it first. But the UK could have worked on maintaining and making more balanced that visa-free status quo and obtained a wide ability for citizens to go and do temporary work in each other’s territories — including musicians.

In the final agreement, that whole mobility section has gone.

The government does not deny that it killed it for ideological reasons. Culture Minister Caroline Dinenage tellingly described the EU mobility offer as “general freedom of movement/work”, as opposed to the “specific provision for musicians/artists” proposed by the UK. Being allowed to work visa-free for 90 days is a far cry from pre-Brexit freedom of movement, but it evidently felt too close to it for this government: an end to freedom of movement must be seen to have been achieved, even if the price is lost opportunities for the UK’s creative sector.

Musicians: a casualty of ideology

I made the point above that it is much easier to be confident about the offers that a party made publicly than the offers that a party claims to have made behind closed doors. The EU’s offer was public – a mobility arrangement that, if accepted, would have given all UK musicians wide rights across the EU to play in gigs, sing in concerts and take up temporary engagements (a part in a show or an opera) for up to 90 days.

The current UK government’s offer was not public and remains unclear: in particular, it is not clear that it would, or could, have covered anything like all musicians. And even if it did cover all musicians, it would also have been subject to the general restrictions and reservations that bedevil those provisions. It can therefore be said with some confidence that the EU’s offer would have offered rather more to UK musicians seeking to play in the EU than the UK offer would have done.

That is not just because it is much clearer what the EU’s offer is. It is also because the EU’s offer was part of a set of provisions designed to preserve aspects of free movement that were valued not just by musicians but also by, for example, young Brits wanting to fund a summer on the Spanish beaches or a winter skiing in the Alps by taking temporary jobs as bar staff or shop assistants. The current UK government’s hostility to the retention of any aspect of free movement doomed that offer from the start.

That hostility meant, however, that the current government could not satisfactorily honour its pledge to preserve rights for the UK’s creative and music sector, as such rights would have had to have been shoehorned in to much more limited sets of provisions, very similar to those agreed in other EU free trade agreements, that were not designed with the position of individuals (apart from a few highly qualified professionals) or the creative sector in mind. They are rather designed to help businesses in traditional services sectors, such as professional and business services, to sell from one party to another.

The blame for the current government’s failure to honour its pledge to the music sector therefore lies firmly on the doorstep of 10 Downing Street. It is a consequence of its determination not to go beyond the narrow, business-orientated provisions of a traditional free trade agreement and not to enter into any form of mobility arrangement that could begin to go towards meeting the current Prime Minister’s pledge, made the day after the referendum result, that “British people will still be able to go and work in the EU; to live; to travel; to study; to buy homes and to settle down”.