- BY Alex Schymyck

Yet more guidance on automatic deportation

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Table of Contents

ToggleThe Upper Tribunal has handed down two cases with guidance on a range of issues relating to the automatic deportation regime. In both cases the appellants sought to rely on statements from the Supreme Court in KO (Nigeria) and Others v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2018] UKSC 53, which held that bad behaviour by parents is irrelevant when decision-makers consider the best interests of children. Unfortunately, neither of the appellants was able to demonstrate that the Supreme Court intended to generally make the automatic deportation regime more liberal. The cases were heard together and are best understood as a pair.

Critical stage of child’s development

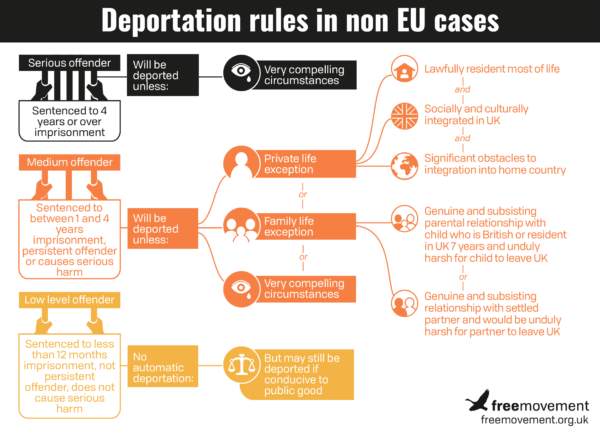

As our infographic below shows, one of the exceptions to automatic deportation is where it would be “unduly harsh” on someone’s child.

In RA (s.117C: “unduly harsh”; offence: seriousness) Iraq [2019] UKUT 123 (IAC), the appellant tried to convince the tribunal that when the Supreme Court approved the test for “unduly harsh” used in an earlier Upper Tribunal judgment, it also approved the factual findings made when applying the test. In particular, the appellant claimed that the Supreme Court approved the Upper Tribunal’s view that children at the age of seven are at a critical stage of development. Unfortunately, this Upper Tribunal rejected that analysis and held that the Supreme Court had only approved the legal test.

Very compelling circumstances

As originally drafted, the automatic deportation rules in section 117C of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 also provide an exception in “very compelling circumstances” — but only for the most serious criminals. In NA (Pakistan) v SSHD [2016] EWCA Civ 662, the Court of Appeal decided that this was obviously a mistake and that “Parliament must have intended medium offenders to have the same fall back protection as serious offenders”. That is the position reflected in our infographic above: “very compelling circumstances” provides an exception to deportation for medium offenders, not just serious offenders.

At the time, Colin wrote that NA (Pakistan) might not survive Supreme Court analysis. What the Upper Tribunal is saying, in the first of the new cases, is that NA Pakistan is still decisive on this point. The judgment confirms that, despite the apparent wording of section 117C, the very compelling circumstances exception is a residual exception which applies to everyone subject to the automatic deportation regime, not just the most serious offenders.

In the second case, MS (s.117C(6): “very compelling circumstances”) Philippines [2019] UKUT 122 (IAC), the Upper Tribunal confirmed that when applying the very compelling circumstances test judge have to consider the seriousness of the person’s criminal offences. Moreover, deterrence remains an important element of the public interest, despite Lord Wilson’s comments in Hesham Ali v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2016] UKSC 60 that it is no longer appropriate to consider the public’s revulsion at crimes committed by foreign nationals.

Assessing seriousness of crimes committed

Back to the first case for guidance on how to assess the seriousness of the criminal offences when applying the very compelling circumstances test. The Upper Tribunal held, following Court of Appeal authority, that when assessing the seriousness of the criminal offences the length of sentence and sentencing remarks made by the Crown Court are the starting point, although tribunal judges can take account of mitigating circumstances.

Rehabilitation unlikely to be relevant

In the most controversial aspect of both decisions, the Upper Tribunal held that rehabilitation since the offences were committed is unlikely to be material when applying the very compelling circumstances test. The tribunal said that not committing criminal offences is a general expectation of people in society and does not justifying giving credit to the individual facing deportation in the balancing exercise:

As a more general point, the fact that an individual has not committed further offences, since release from prison, is highly unlikely to have a material bearing, given that everyone is expected not to commit crime. Rehabilitation will therefore normally do no more than show that the individual has returned to the place where society expects him (and everyone else) to be. There is, in other words, no material weight which ordinarily falls to be given to rehabilitation in the proportionality balance (see SE (Zimbabwe) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2014] EWCA Civ 256, paragraphs 48 to 56). Nevertheless, as so often in the field of human rights, one cannot categorically say that rehabilitation will never be capable of playing a significant role (see LG (Colombia) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2018] EWCA Civ 1225). Any judicial departure from the norm would, however, need to be fully reasoned.

RA case, paragraph 33

On this issue the Upper Tribunal has not paid enough attention to existing Court of Appeal authority. It cites SE (Zimbabwe) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2014] EWCA Civ 256, in which the Court of Appeal held that the fact that there would be no rehabilitation programmes available to the individual on return was irrelevant. The issue here is rehabilitation which has already occurred by the time the tribunal considers the case, rather than the future prospects of rehabilitation. As the Court of Appeal acknowledged in LG (Colombia) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2018] EWCA Civ 1225, which was also cited by the Upper Tribunal, rehabilitation can be a relevant factor.

For the most part the guidance issued by the Upper Tribunal in these two appeals is the product of careful consideration of decisions of the Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court. Unfortunately, on the issue of rehabilitation the Upper Tribunal has misunderstood existing Court of Appeal authority and issued inaccurate guidance. Rehabilitation is unlikely to be a weighty or decisive factor, but it has a role in identifying whether there are very compelling circumstances which outweigh the public interest in deportation. The Upper Tribunal’s view is needlessly harsh and will hopefully be corrected by the Court of Appeal.

The headnotes for both cases are:

RA (s.117C: “unduly harsh”; offence: seriousness) Iraq [2019] UKUT 123 (IAC):

(1) In KO (Nigeria) & Others v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2018] UKSC 53, the approval by the Supreme Court of the test of “unduly harsh” in section 117C(5) of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002, formulated by the Upper Tribunal in MK (Sierra Leone) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2015] UKUT 223 (IAC), does not mean that the test includes the way in which the Upper Tribunal applied its formulation to the facts of the case before it.

(2) The way in which a court or tribunal should approach section 117C remains as set out in the judgment of Jackson LJ in NA (Pakistan) & Another v Secretary of State [2016] EWCA Civ 662.

(3) Section 117C(6) applies to both categories of foreign criminals described by Lord Carnwath in paragraph 20 of KO (Nigeria); namely, those who have not been sentenced to imprisonment of 4 years or more, and those who have. Determining the seriousness of the particular offence will normally be by reference to the length of sentence imposed and what the sentencing judge had to say about seriousness and mitigation; but the ultimate decision is for the court or tribunal deciding the deportation case.

(4) Rehabilitation will not ordinarily bear material weight in favour of a foreign criminal.

MS (s.117C(6): “very compelling circumstances”) Philippines [2019] UKUT 122 (IAC)

(1) In determining pursuant to section 117C(6) of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 whether there are very compelling circumstances, over and above those described in Exceptions 1 and 2 in subsections (4) and (5), such as to outweigh the public interest in the deportation of a foreign criminal, a court or tribunal must take into account, together with any other relevant public interest considerations, the seriousness of the particular offence of which the foreign criminal was convicted; not merely whether the foreign criminal was or was not sentenced to imprisonment of more than 4 years. Nothing in KO (Nigeria) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2018] UKSC 53 demands a contrary conclusion.

(2) There is nothing in Hesham Ali v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2016] UKSC 60 that requires a court or tribunal to eschew the principle of public deterrence, as an element of the public interest, in determining a deportation appeal by reference to section 117C(6).

For more on deportation law, try the Free Movement advanced online training course on Deportation of non EU and EU nationals: 4 CPD.