- BY Colin Yeo

Supreme Court: bad behaviour by parent irrelevant to best interests of children

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

The Supreme Court has today handed down judgment in four linked cases all concerning the best interests of children who themselves face removal from the UK or whose parent faces removal from the UK. The case is likely to be referred to as KO (Nigeria) and Others v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2018] UKSC 53.

The cases concern the new scheme of prescriptive immigration rules introduced by Theresa May as Home Secretary in 2012, bolstered by statutory reinforcement in the Immigration Act 2014. These provisions were intended to reduce judicial discretion. The reality has been a mess of conflicting and confusing decisions.

Summary

The short take away from the judgment is that where the scheme of immigration law sets out a discretionary assessment of the impact of removal on a child using a “reasonableness” or “undue harshness” test, the conduct of the parent is irrelevant to that assessment of the impact on the child. This overrules earlier tribunal and Court of Appeal authority to the contrary.

The reasoning is essentially that the conduct of the parent will already have been considered earlier in the prescribed assessment process and that “a child must not be blamed for matters for which he or she is not responsible, such as the conduct of a parent” (see earlier case of Zoumbas v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2013] UKSC 74).

The procedural history to the four cases is complex and the cases have gone by different names at every stage of the appeal process, it seems. There is no need to delve into that here to understand what the Supreme Court tells us in this judgment, though.

Paragraph 276ADE(1)(iv): “reasonable”

Paragraph 276ADE(1)(iv) of the Immigration Rules provides that a child be permitted to remain where the child “has lived continuously in the UK for at least seven years (discounting any period of imprisonment) and it would not be reasonable to expect the applicant to leave the UK”.

Lord Carnwath could not be clearer in finding that this paragraph is directly solely to the position of the child. Unlike the predecessor policy, known as DP5/96, it contains no reference to the criminality or misconduct of the parent. He concludes:

It is impossible in my view to read it as importing such a requirement by implication.

However, Lord Carnwath goes on to find that the immigration status of the parent or parents is indirectly relevant to the consideration of whether it is reasonable for a child to leave the UK. He quotes the question posed by Lewison LJ in EV (Philippines) [2014] EWCA Civ 874:

Thus the ultimate question will be: is it reasonable to expect the child to follow the parent with no right to remain to the country of origin?

This is not to say, though, that poor immigration history on the part of the parent justifies removal of a child. This would represent a gloss on the test. And as we see in a moment, the status of the parent will follow that of the child because of the effect of section 117B.

Section 117B: “reasonable”

The language and structure of section 117B of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 (introduced by the Immigration Act 2014) is very similar to paragraph 276ADE(1)(iv) of the Immigration Rules. The main differences are that s.117B:

- applies only to tribunals and courts, not officials at the Home Office

- is directed to the parent whereas paragraph 276ADE(1)(iv) is directed to the child.

Unsurprisingly, then, Lord Carnwath holds that the same approach applies to s.117B as to paragraph 276ADE(1)(iv). The conduct of the parents is not relevant to the assessment of whether it is reasonable for the child to leave the UK, although given that in most cases one or both parents will not have status the question will then be whether it is reasonable for the child also to leave the UK with the parent.

Section 117B also perhaps answers for us the question of what happens where it is not reasonable for a child to leave the UK. Paragraph 276ADE(1)(iv) is silent on this, although logically it would seem that the parent must therefore be allowed to stay with the child. This is surely confirmed by section 117B, which is directed to the position of the parent not the child.

Section 117C: “unduly harsh”

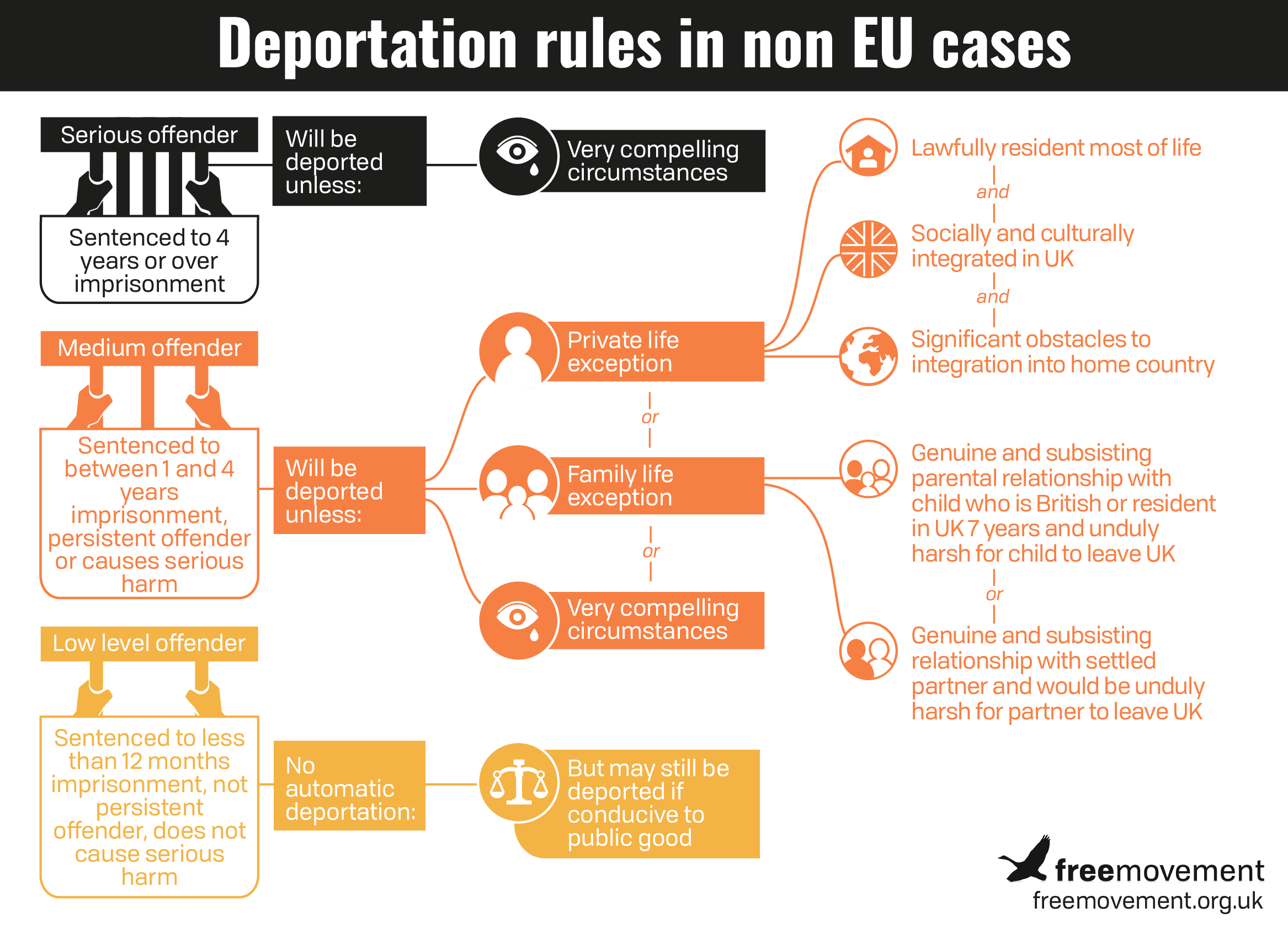

Section 117C of the NIAA 2002 is intended to be a self contained code dictating when foreign criminals might be permitted to remain in the UK and when they should be deported:

The presumption is that any foreign criminal, defined broadly as a migrant sentenced to 12 months or more in prison, should be deported unless one of three exceptions applies. The first two exceptions are not available if the foreign criminal is sentenced to four years’ or more in prison, although there is still an “very compelling circumstances” exception available.

The first exception, on private life, is principally about length of residence in the UK and was not in issue in these cases.

The second exception, on family life, is often about the impact of deportation on an affected child, and this was very much in issue:

Exception 2 applies where [the foreign criminal] has a genuine and subsisting relationship with a qualifying partner, or a genuine and subsisting parental relationship with a qualifying child, and the effect of [the foreign criminal]’s deportation on the partner or child would be unduly harsh.

Lord Carnwath holds at paragraphs 22 and 23 of the judgment that exception 2 is self contained and does not include consideration of the parent’s conduct. However, the test is a harsher one than the “reasonableness” one in paragraph 276ADE(1)(iv) and section 117B because section 117C concerns foreign criminals not just ordinary migrants.

To take a different approach conflicts with the structure and intention of section 117C and conflicts with the Zoumbas principle that the child should not be held responsible for the conduct of the parent. The tribunal should not be expected, for example, to decide whether consequences which are deemed unduly harsh for the son of an insurance fraudster may be acceptably harsh for the son of a drug-dealer, it being rather difficult to reach a rational conclusion on such a question.

Outcomes

The outcome on the law is therefore a positive one for children and their parents. Poor conduct of a parent is not relevant to assessing whether it is reasonable for a child to have to leave the UK and, having already been considered in the structured assessment required by section 117C, it is not considered again when assessing whether removal of the parent would have an unduly harsh effect on the child.

However, this is little consolation to the parents or children in two of the four cases. The appeals to the Supreme Court are technically dismissed in all four cases, but the actual effect in IT and AP is that the orders of the Court of Appeal to send the appeals back to the tribunal is upheld,

The rejection of the appeal in KO seems particularly surprising given that the reasoning of Judge Southern below was comprehensively rejected, only for Lord Carnwath to conclude that he somehow got it right anyway.

Leapfrogging

Finally, Lord Carnwath is not impressed by the “unhappy drafting of the statutory provisions”, nor with the Secretary of State’s shifting and incorrect interpretation of them, nor with Tribunal Judge Southern’s breach of judicial comity in departing from earlier tribunal authority to create a conflict at tribunal level.

He urges the tribunal to resurrect the effectively defunct starred decision system and to consider issuing “leapfrog” certificates enabling the Supreme Court to consider important issues without the delays caused by Court of Appeal consideration.

I can see the attraction of such leapfrogging. The arguments presented to the Court of Appeal tend to be much more refined than before the tribunal and going through the tribunal and the Court of Appeal gives everyone an opportunity to really think through the issues. As a lawyer it “feels” like a useful and necessary process.

Frankly, though, these “refinements” at the Court of Appeal stage often prove to be more like obfuscations. Once a case reaches the Supreme Court, their Lord and Ladyships have to just cut through the resulting mess. Perhaps it is time to abandon bedevilled argument on the quantum of angels.

SHARE

4 responses

Colin, IT was remitted too.

Good spot, amended it, thanks!

I must say, the decision in NS was the most mind-boggling for me…

If one looks at the case of NS, then this really is approving EV (Philippines) and stating that if parents being removed as they have no status, then in the vast majority of cases it is reasonable for children to be removed with the parents. Thus, this decision only assists children where the parents have a right to remain in the UK – if the parents have no right to remain, then even if it is in the best interests of the children to remain in the UK, it will be reasonable for the children to be removed with the parents.

Thus, I cannot see this case helping the vast majority of cases that I see which are ones involving children who have been in the UK many years and are very clearly settled here, but where the parents are here unlawfully. These cases will fail in all but the most exceptional circumstances.

Or am I missing something?