- BY Fahad Ansari

Victim of brutal domestic abuse loses appeal against deprivation of British citizenship

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Table of Contents

ToggleA mother of three British children has lost her appeal against the decision of Amber Rudd to take away her British citizenship in 2017. The judgment of the Special Immigration Appeals Commission (SIAC) makes for very grim reading.

The woman, anonymised as “U3”, was born in the UK with British and Moroccan citizenship. Her dual nationality would turn out not to be an asset, but a perilous liability that would ultimately render her a second-class citizen who could be banished and left in exile.

Background

U3 spent her entire childhood in the UK. In 2011, at the age of 18, she married her husband (“O”) against her family’s wishes. She became a mother at the age of 19, gave birth again the following year and by the time she turned 21, found herself crossing the border from Turkey into ISIL-controlled territory with her husband and children. U3 gave birth to her third child in Syria in 2016.

In April 2017, then Home Secretary Rudd deprived U3 of her citizenship on the basis that it was conducive to the public good to do so. U3 was assessed as having travelled to Syria, being aligned to ISIL and presenting a threat to UK national security. U3’s deprivation order was just one of a record 104 such orders signed by Rudd that year. In May 2018, U3 appealed the decision to SIAC.

In 2019, U3’s children were repatriated to the UK but her own application to join them the following year was refused by Priti Patel. SIAC heard her appeals against both the deprivation decision and the refusal to grant entry clearance to the UK towards the end of 2021.

Domestic abuse

In the UK

U3 argued that she had not travelled to Syria voluntarily, that she was not and had not ever been aligned with ISIL and did not present a threat to national security. The primary factor that led to her being in ISIL-controlled territory was a controlling and abusive marriage. Her account was strongly supported by Dr Roxane Agnew-Davies, a clinical psychologist and member of a government taskforce on violence against women and children, as well as “radicalisation experts” Professor Andrew Silke and Dr Katherine Brown.

SIAC accepted that U3 had been subjected to serious and sustained violence by her husband, identifying it as “a dominant feature of their relationship”. That violence included:

- Punching, kicking and violently penetrating her on their wedding night in April 2011

- Hitting her in the face with a slipper and punching her in August 2011

- Beating her in April 2012 while she was pregnant for having visited her mother without his permission

- Beating her in February 2013 while six months pregnant and anaemic to the point of her collapsing and being taken by ambulance to hospital

- Beating her in January or February 2014 in front of her parents

Notably, SIAC accepted that U3 was violently beaten specifically for refusing to go to Syria, in both March and June 2014. Police records even confirmed U3’s call to them reporting the latter attack.

Just two weeks after that call, U3 travelled with her two children to Turkey. By this stage, O was threatening to marry another woman to travel to Syria with him. U3 acted upon advice from a friend of O that going to Turkey would help save her marriage as it would demonstrate her commitment to the plan to move to Syria. Critically, SIAC accepted that part of U3’s motivation was her knowledge that O was banned from entering Turkey and so she could prove herself to O with little risk of him actually joining her there. Unfortunately, O did manage to enter Turkey in mid-August 2014.

On both 20 August 2014 and 21 August 2014, U3 told O that she did not want to go to Syria. On each occasion, O physically assaulted U3 as a result. On the second occasion, O ripped up the children’s passports and threatened to take them to Syria without U3. SIAC completely accepted U3’s account in this regard.

It was against this background that U3 entered Syria with her husband and children on 22 August 2014.

In Syria

SIAC also agreed that, while in Syria, U3 continued to be subjected to the most horrific physical and sexual violence by her husband. This included breaking her ankle, beating her with a metal rod, locking her in the bedroom, raping her and subjecting her to regular beatings with his fists and with weapons.

But SIAC went even further and agreed with Dr Agnew-Davies that U3 was subjected to the following elements of coercive control: “threats, surveillance, degradation, shaming, isolation from family and friends, false imprisonment, control of her means of escape, control of her finances, control of almost every aspect of her personal and social life, conduct designed to make her doubt her own sanity (‘gaslighting’), and micro-regulation of her dress and behaviour”.

The Home Office was gracious enough to concede that U3 “had a difficult relationship with her husband”.

SIAC’s decision

SIAC recognised that it was in the best interests of U3’s children for her to be with them in the UK, that they were very emotionally attached to her, and that her presence would assist their recovery from the trauma they had suffered in Syria.

Yet notwithstanding its recognition that the systematic abuse U3 was subjected to had a “major impact” on the way she made decisions for herself and her children, SIAC found that when U3 decided to travel to Turkey, she had the contingent intention of travelling to Syria with her husband if necessary, knowing it might actually happen. As she must have known he was aligned to ISIL, SIAC held that her travel there was to offer her support to him as a wife and as the mother of his children.

With respect, such a conclusion requires a significant degree of mental gymnastics.

Ultimately, despite hinting at several points that it might have decided the case differently had it the power to do so, SIAC dismissed U3’s appeal on the basis that it could not substitute its own decision on matters of national security in place of that of the Home Secretary; its hands were tied by the Supreme Court decision in Shamima Begum that the courts must give the Home Secretary’s assessment due respect. It could only interfere if the decision was flawed according to the public law standard of review, and the outcome, but for the error, would have been different.

Rigged system, perverse outcome

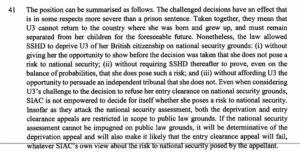

Paragraph 41 of the judgment summarises everything that is so fundamentally wrong about the SIAC regime and why many sympathise with the view that the system is rigged against appellants.

If SIAC, having considered both the open and closed (secret) evidence, is of the view that an appellant like U3 did not align herself with ISIL and does not pose a threat to national security in 2022, and where there is incredibly powerful evidence of grooming, trafficking and modern slavery, it seems perverse for it not to have the power to overturn the Home Secretary’s assessment made over five years earlier (without consideration of that same material).

The Supreme Court insists that courts must give due respect and deference to the assessment of the Home Secretary because she is accountable to Parliament and is advised by the security services. Yet SIAC’s closed procedure gives it access to the same intelligence and information that was available to the Home Secretary. If SIAC’s power, even where it assesses an appellant as posing no threat to national security, is limited by Begum to checking the rationality of the Home Secretary’s decision, it is virtually impossible for any appellant to succeed.

Ultimately, it is tragic victims like U3 and her children who will receive life sentences because of this heartless, unforgiving regime. To the lay observer, SIAC’s treatment of U3 may give the impression that the separation of powers doctrine has been abandoned in the interests of national security — with the net result being the forcible separation of an innocent, brutalised mother from her already traumatised children.

Those of us in the legal profession, and in particular the Special Advocates who represent clients before SIAC, should be asking ourselves a fundamental question: if a judicial body that is already so inherently unfair (as the Court of Appeal has confirmed was Parliament’s intention when creating it) is now hamstrung to the extent that its role is effectively confined to rubber-stamping national security decisions of the executive, is it ethically and morally right to participate in such a system?