- BY Nick Nason

What does “unduly harsh” mean in deportation cases?

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Page contents

In the case of Secretary of State for the Home Department v PG (Jamaica) [2019] EWCA Civ 1213 the Court of Appeal considered the meaning of “unduly harsh” in deportation cases, overturning the decisions of both of the tribunals that had previously heard the appeal.

In this post we look at the way in which the court is interpreting this test, and what it means for appellants (and lawyers) preparing their cases.

The KO (Nigeria) test

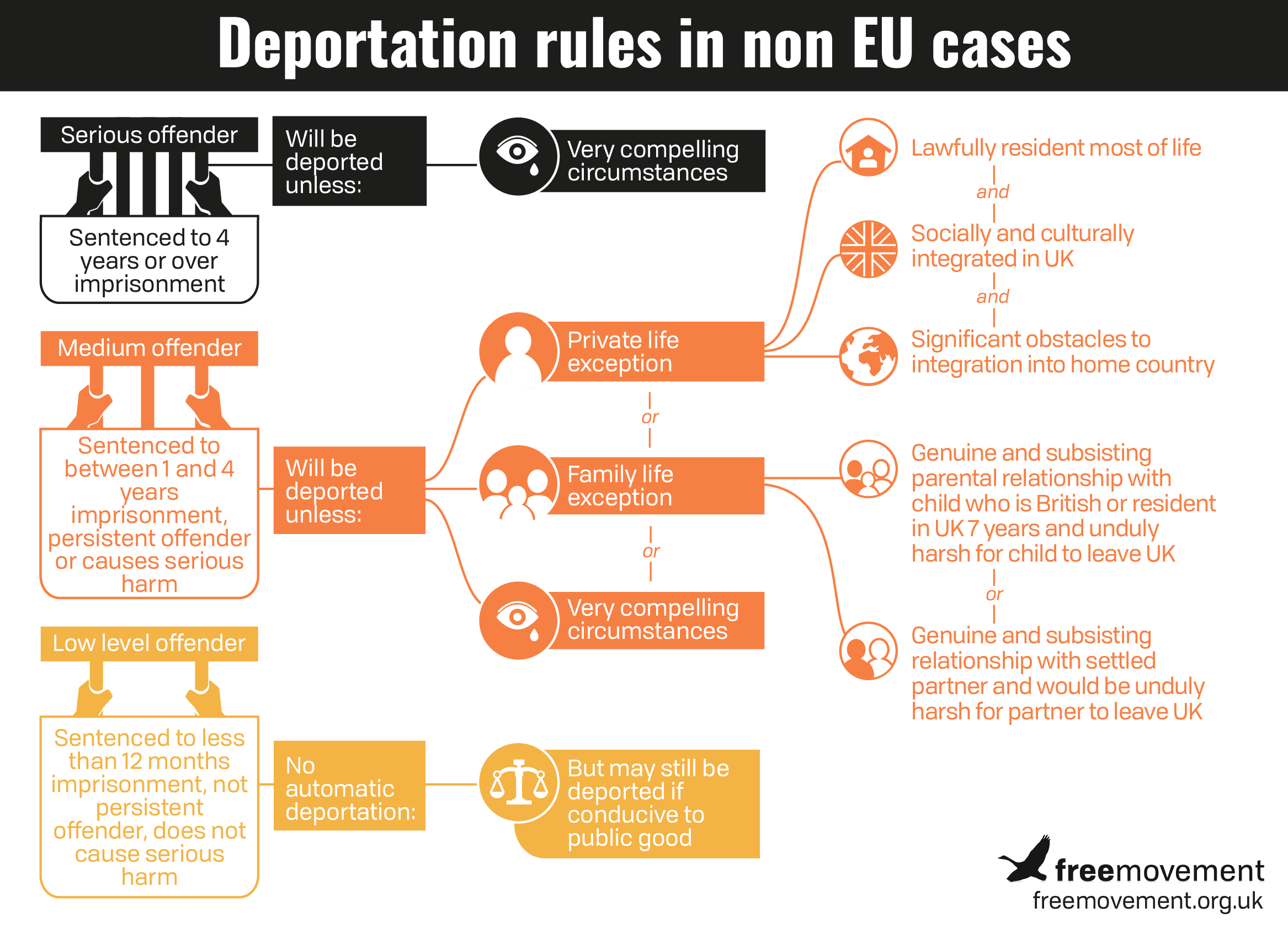

Foreigners sentenced to between 1-4 years’ imprisonment can usually expect to be deported from the UK unless they fit within an exception.

One of those exceptions is where the foreign citizen has a “genuine and subsisting” parental relationship with a child, and the effect of deportation on the child would be “unduly harsh” (section 117C(5) of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002).

The Supreme Court in KO (Nigeria) v SSHD [2018] UKSC 53 provided guidance on what “unduly harsh” meant, explaining that for foreign criminals to succeed in resisting deportation they would need to show:

a degree of harshness going beyond what would necessarily be involved for any… child of a foreign criminal facing deportation.

The Court of Appeal has now applied this test in PG (Jamaica), a case involving a foreign national offender sentenced to just under 3 ½ years for a drugs-related offence in 2009, and some non-custodial offences later.

PG lived with his partner and three children, in whose lives he reportedly played an active role. His deportation, the court accepted, would lead to emotional and behavioural problems on the part of his three children and cause them great distress.

Although PG had succeeded at his initial First-tier Tribunal hearing, and that decision was undisturbed by the Upper Tribunal, the Court of Appeal allowed the Secretary of State’s appeal. Giving judgment, Lord Justice Holroyde explained at paragraph 39 that

I recognise of course the human realities of the situation, and I do not doubt that [PG’s partner] and the three children will suffer great distress if PG is deported. Nor do I doubt that their lives will in a number of ways be made more difficult than they are at present. But those, sadly, are the likely consequences of the deportation of any foreign criminal who has a genuine and subsisting relationship with a partner and/or children in this country.

The Court of Appeal held that the effect on the three children would “not go beyond the degree of harshness which is necessarily involved for the… child of a foreign criminal who is deported”.

Interpretation of KO in the Court of Appeal

Is the Court of Appeal correct in its interpretation of the KO (Nigeria) test?

The key here is that a qualifying child in these cases is one with whom a foreign criminal has a “genuine and subsisting” relationship.

The phrase “genuine and subsisting” does not necessarily mean emotionally dependant. It does not mean devoted. It does not even mean, necessarily, loving.

But, as quoted above, the Court of Appeal held here that great distress and difficulties would be caused by the deportation of any foreign criminal who has a genuine and subsisting relationship with a child in the UK.

The result of this logic seems to be that emotional reliance and devotion have been priced into the test constructed by the Supreme Court in KO (Nigeria). The result is that foreign criminals are now effectively expected to show

a degree of harshness going beyond what would necessarily be involved for any emotionally dependant child of a foreign criminal facing deportation who loves their child and is an important part of their lives.

The Court of Appeal has arguably baked normative ideals of parenthood into the Supreme Court test, which assumes that all children depend on their parents to the same extent, and would react to their deportation in the same way.

The Cinderella Test

But this isn’t true, is it.

Take Cinderella, for instance. It would be difficult to argue that she did not have a “genuine and subsisting” parental relationship with her wicked stepmother.

Let us assume that Cinderella’s stepmother was a foreign national, and received a sentence of more than 12 months’ imprisonment.

I doubt Cinderella would be “greatly distressed” by her step-mother’s deportation, as this application of the KO (Nigeria) test assumes.

But, according to the Court of Appeal, the hypothetical child at the heart of the KO (Nigeria) test is emotionally dependant on the foreign national criminal.

It is the harshness of the rupture caused by deportation and suffered by this hypothetical child which has been interpreted as duly harsh, and where the baseline now sits.

This being the case, it is increasingly difficult to see that there is much to be distinguished between a “degree of harshness going beyond” the duly harsh argument under section 117C(5), and a “very compelling circumstances” argument under section 117C(6).

This arguably flies in the face of the statutory scheme, which is constructed to penalise those who have been sentenced to longer periods of incarceration.

The wrong hypothetical child

Is the Court of Appeal using the wrong hypothetical child?

The court would, I am sure, accept that there is going to be a spectrum of distress suffered by children whose parents are being deported, with Cinderella at the bit-miffed-but-generally-ok end of it.

Albeit in the context of marriage, we know from Goudey [2012] UKUT 41 (IAC) that a “genuine and subsisting” relationship must simply exist beyond formal recognition. Devotion is not necessarily a constituent part, nor emotional reliance or dependence, nor love.

Given that the statutory framework expressly refers to the contemplated parental relationship as one which is “genuine and subsisting”, one might argue that the hypothetical child in the KO (Nigeria) test should be somewhere much closer on the spectrum to Cinderella than has been found to be the case here.

No midnight reprieve

This is one of several dispiriting aspects of PG (Jamaica).

Others include the decision (in what appears to be a developing trend) not to remit the case back to the tribunals for final disposal, and the reversal of yet another tribunal decision due, essentially, to a disagreement with the findings of the lower courts.

What is clear is that, unless and until the Court of Appeal revisits the way in which it is applying the KO (Nigeria) test, even appellants sentenced to fewer than four years in prison face an uphill struggle to challenge attempts to deport them.

SHARE