- BY Colin Yeo

Supreme Court pronounces on “unduly harsh” deportation test, again

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

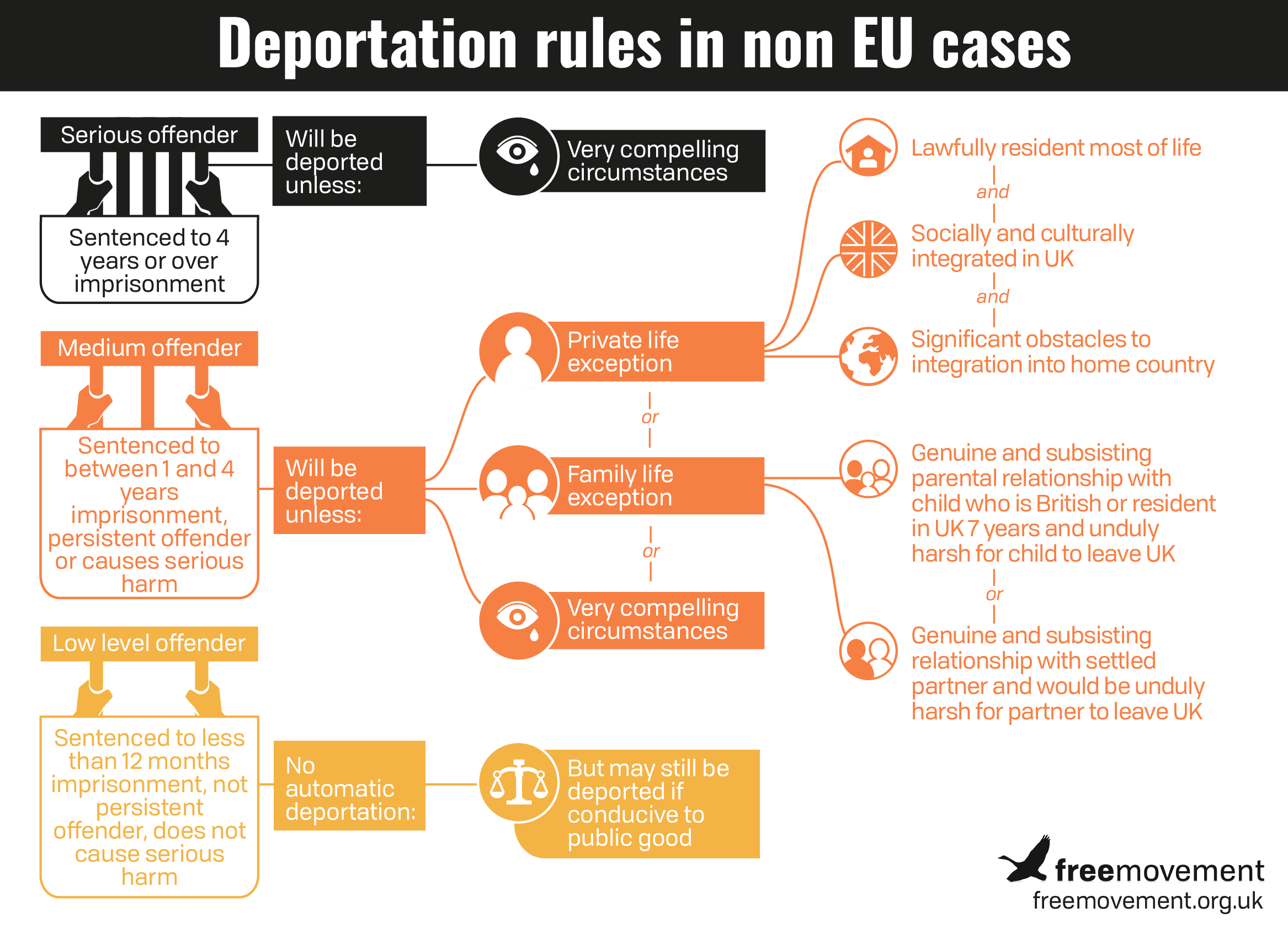

In what I calculate to be the fifth Supreme Court case addressing the meaning of the words used in Theresa May’s 2014 reforms of deportation law, the justices have rejected three linked Home Office appeals seeking to reinstate deportation orders. The previous cases were, in reverse order, SC (Jamaica), Sanambar, Rhuppiah and KO (Nigeria). That’s not to mention Hesham Ali on the forerunner 2012 reforms. So much for adding clarity to the law: I count 25 blog posts on Free Movement mentioning just KO (Nigeria).

The latest addition to this pantheon of perplexity is the case of HA (Iraq) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2022] UKSC 22. The judgment is given by Lord Hamblen with the agreement of the rest of the panel.

The main focus of the case is the meaning of the words “unduly harsh” in section 117C(5) of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 as amended. Broadly, these words form part of the test for whether a foreign criminal is exempted from deportation. If the impact on the person’s partner or child would be unduly harsh then the person should not be deported.

But what does “unduly harsh” mean and how is the concept to be judged?

Meaning of unduly harsh

Unhappy about an earlier Court of Appeal ruling about the meaning of “unduly harsh” in cases affecting children, the Home Office was attempting to persuade the Supreme Court to follow a different approach. The government relied on remarks by Lord Carnwath in the previous Supreme Court judgment in KO (Nigeria), which had previously been considered by the tribunal and Court of Appeal to set a very stringent test in deportation cases. These cases — which the Home Office rather liked and wanted to revert to — took a single sentence of Lord Carnwath’s judgment and transformed it into a test that was almost impossible to meet:

One is looking for a degree of harshness going beyond what would necessarily be involved for any child faced with the deportation of a parent.

One obvious problem with using this as the definitive test is that there is no fixed reference point for judging an individual case. The comparator is entirely notional. It is, as Nick Nason wrote for us, akin to the Blackadder scene in which Percy attempts to explain the blueness of the Spanish Infanta’s eyes (which he has not seen) by reference to the Blue Stone of Galveston (which he also hasn’t seen). Given that the loss of a parent is inherently traumatic, the tribunal and Court of Appeal subsequently decided, something more than trauma was needed to trigger the “unduly harsh” exemption. Something like diagnosable psychiatric injury.

How judges managed to manoeuvre themselves into a position where it was possible to write such things and also maintain the pretence that the statutory scheme was compatible with Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights, never mind more straightforward simple humanity, is a mystery. An unknown number of children were then separated from their parents on this basis over the next couple of years.

In his judgment in the Court of Appeal in September 2020, Lord Justice Underhill, who has become the unofficial Mr-Fix-It of immigration law, pointed out a number of flaws with the approach preferred by the Home Office. These included that there is no satisfactory way to define the relevant characteristics of a notional comparator child or to make any such comparison workable; that such an approach is inconsistent with the duty to have regard to the best interests of children; and the risk that officials and judges would apply an exceptionality threshold that is not justified on the face of the legislation.

In a rare revival of a McCloskey-era decision, the Supreme Court points us to a passage in MK (Sierra Leone) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2015] UKUT 223 (IAC) at paragraph 46, which was endorsed by Lord Carnwath in KO (Nigeria) and is re-endorsed by Lord Hamblen:

By way of self-direction, we are mindful that “unduly harsh” does not equate with uncomfortable, inconvenient, undesirable or merely difficult. Rather, it poses a considerably more elevated threshold. ‘Harsh’ in this context, denotes something severe, or bleak. It is the antithesis of pleasant or comfortable. Furthermore, the addition of the adverb “unduly” raises an already elevated standard still higher.

While this can be criticised as glossing the statutory language, Lord Hamblen wryly observes that “it is apparent that the statutory language has caused real difficulties for courts and tribunals”.

The unduly harsh test is clearly not easy to meet. But it is not as impossible or inhumane as was made out in a string of cases now thankfully consigned to history.

Meaning of very compelling circumstances

Next, Lord Hamblen turns to the “very exceptional circumstances” test. There’s nothing new here, I think, just a recital of the existing legal position. In short, the case law emphasises that the test is not an easy one to meet and the public interest in deportation is a very weighty factor. But that the ultimate threshold is whether the deportation would breach Article 8.

In the recent case of Unuane v United Kingdom (application no. 80343/17), the European Court of Human Rights re-stated the basic approach laid down in the earlier leading and well-known cases of Boultif v Switzerland and Uner v Netherlands:

• the nature and seriousness of the offence committed by the applicant;

• the length of the applicant’s stay in the country from which he or she is to be expelled;

• the time elapsed since the offence was committed and the applicant’s conduct during that period;

• the nationalities of the various persons concerned;

• the applicant’s family situation, such as the length of the marriage, and other factors expressing the effectiveness of a couple’s family life;

• whether the spouse knew about the offence at the time when he or she entered into a family relationship;

• whether there are children of the marriage, and if so, their age; and

• the seriousness of the difficulties which the spouse is likely to encounter in the country to which the applicant is to be expelled …

• the best interests and well-being of the children, in particular the seriousness of the difficulties which any children of the applicant are likely to encounter in the country to which the applicant is to be expelled; and

• the solidity of social, cultural and family ties with the host country and with the country of destination.

Nevertheless, “[t]he weight to be given to the relevant factors falls within the margin of appreciation of the national authorities” (paragraph 52).

Relevance of rehabilitation

The specific issue of the relevance of rehabilitation has been a controversial one, with the tribunal suggesting it ought properly be considered irrelevant. This is because rehabilitation merely suggests “the individual has returned to the place where society expects him (and everyone else) to be”. Rowing back from his endorsement of this statement, which has considered to be wrong in some Court of Appeal judgments, Lord Hamblen concedes that if there is “evidence of positive rehabilitation which reduces the risk of further offending then that may have some weight as it bears on one element of the public interest in deportation, namely the protection of the public from further offending” (paragraph 58).

He also signals for the future that taking into account public concern in an Article 8 balancing exercise may potentially not be permissible given that it is not necessarily one of the relevant considerations listed in Article 8(2). This remains for decision in another case.

Relevance of criminal sentence

The seriousness of an offence is something that must be considered according to both the domestic statutory scheme and Strasbourg jurisprudence. But it can be difficult for an immigration judge to determine seriousness several years on without having heard the evidence in the criminal trial or having the experience of a criminal judge. It has been suggested that the length of sentence be the single determinant of seriousness as far as immigration judges are concerned.

The problem is that a sentence imposed by a court “may well reflect various considerations other than the seriousness of the offence” (paragraph 66). These include aggravating and mitigating factors, some of which might relate to the seriousness of the offence and some of which might not. Previous offending is generally relevant but tells us nothing of the seriousness of the specific offence triggering deportation, for example. Credit is also given for a guilty plea, which once again is not relevant to the seriousness of the offence.

Lord Hamblen suggests that the length of sentence should be the starting point and, often but not always, the ending point for judging the seriousness of the offence. If other information is available, it can be considered:

In practice, however, an immigration tribunal may have no information about an offence other than the sentence. If so, that will be the surest guide to the seriousness of the offence. Even if it has the remarks of the sentencing judge, in general it would only be appropriate to depart from the sentence as the touchstone of seriousness if it is clear from those remarks that factors unrelated to the seriousness of the offence have influenced the sentence arrived at and how they have done so. In relation to credit for a guilty plea that will or should be clear. If so, then in principle I consider that that is a matter which can and should be taken into account in assessing the seriousness of the offence.

Lord Hamblen also notes that the nature as well as the seriousness of the offence can and should be considered. Double-counting should be avoided, but the nature of offending can be relevant.

Re-writing the statutory scheme

At the risk of sounding like a broken record, I note that Lord Hamblen re-endorses the re-writing of the 2014 statutory scheme by the Court of Appeal in NA (Pakistan) [2016] EWCA Civ 662. The Supreme Court recently did the same in SC (Jamaica) [2022] UKSC 15. Essentially, the Court of Appeal inserted a new statutory exception into the scheme for “medium level” offenders, which also has the side effect of lessening the impact of the statutory language for high-level offenders. This remarkable — but very welcome — feat is accomplished simply by noting a concession to that effect by the Home Office:

This was common ground before us and I shall proceed on the basis that it is correct.

It is intriguing if sterile to contemplate what might have happened — or what might happen in future — if the Home Office had not made or attempted to withdraw this concession. We saw the Supreme Court simply re-write statute in Romein [2018] UKSC 6, so it is something that can potentially happen. But this is not an explicit power bestowed on the Supreme Court by legal precedent or by statute.

Outcome of the individual appeals

All three deportation appeals — which the First-tier Tribunal had orginally allowed — were remitted to the Upper Tribunal for new decisions in which the tribunal should follow what has now been established to be the correct approach.

Lord Hamblen emphasises at paragraph 72 that the Upper Tribunal and Court of Appeal should be slow to interfere with decisions made by specialist fact-finding tribunals. We have certainly seen in recent years a considerable number of Upper Tribunal decisions in which deportation appeals allowed in the First-tier Tribunal have been wrongly overturned.

SHARE