- BY Colin Yeo

Supreme Court allows foreign criminal deportation case

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

The Supreme Court has allowed the appeal against the deportation of a Jamaican man who arrived in the UK aged ten. The case is SC (Jamaica) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2022] UKSC 15. The judgment covers the application of the concept of internal relocation to risk of breaches of Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights and the proper approach to the statutory deportation rules on Article 8 private and family life introduced by the Immigration Act 2014.

SC had a very troubled and difficult upbringing. His mother experienced persecution in Jamaica as a lesbian woman and SC suffered alongside her. She fled to the United Kingdom and was granted asylum. He joined her in 2001. He was deeply traumatised, suffered from complex mental health issues and was described by an expert as “institutionalised”. He had also committed numerous offences. In 2012 he was convicted of assault occasioning actual bodily harm, having an article with a blade, and breach of an anti-social behaviour order. He was sentenced to a period of two years’ detention in a young offender institution.

This sentence triggered deportation action against him, which commenced in 2013. His appeal was heard and allowed in 2015 in the First-tier Tribunal. The Upper Tribunal upheld this decision the same year. The Court of Appeal intervened to overturn it in 2017 but SC appealed to the Supreme Court.

SC had originally been recognised as a refugee. This aspect of his case fell away early in proceedings on the basis that he had committed a particularly serious crime and constituted a danger to the community, meaning that he was no longer protected by Article 33 of the Refugee Convention from refoulement back to Jamaica.

Internal relocation

It was accepted that SC could not live in urban areas in Jamaica because if he did so he would experience treatment amounting to a breach of Articles 3 and 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights. The question then arose of whether SC could live in a rural area instead.

Giving the judgment of the court, Lord Stephens recites the relevant law on internal relocation in the context of the Refugee Convention. This includes the Immigration Rules, the EU’s Qualification Directive and the House of Lords cases of Januzi v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2006] UKHL 5 and AH (Sudan) v Secretary of State for the Home Department (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees intervening) [2007] UKHL 49.

A person will be entitled to refugee status if they will be persecuted in their home area and it is not reasonable to expect them to relocate. The test of whether it would be reasonable has, for reasons which continue to escape me, been reformulated in case law as whether it would be “unduly harsh” for the refugee to relocate. As if that is any clearer. What the cases do make clear is that the test is not an easy one to satisfy. As Lord Stephens puts it at paragraph 60, “the stringency of the reasonableness test is not to be underestimated”.

Based on a concession by the Home Office, the Supreme Court proceeded on the basis that this test is equally applicable in cases based on Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights (para 36).

The First-tier Tribunal judge found that if SC moved to a rural area of Jamaica to avoid his and his mother’s persecutors, “he would be unsupported, homeless, destitute, unemployed and in need of psychological treatment.” This was not reasonable, and the appeal was therefore allowed. The Upper Tribunal upheld this finding. The Court of Appeal did not, however. The Court of Appeal considered that the internal relocation test should be applied differently where a person had committed a criminal offence on the basis that “the phrase ‘unduly harsh’ imports a value judgment of what is ‘due’ to the person”. In short, a criminal might be “due” more harsh treatment than a non-criminal.

The Supreme Court was having none of it. Counsel for the Home Office, Zane Malik QC, conceded that the public interest in deporting foreign criminals cannot render internal relocation reasonable or not unduly harsh (para 93). Lord Stephens noted this concession was “correct” (which contrasts with his simple recording of the fact of other key concessions) and goes on to say that the test

does not take into account what is “due” to the person as a criminal. There is no support for such an approach in domestic authority or in authority in any other jurisdiction.

If anything, he goes on to observe, being a convicted criminal might make internal relocation harder: “criminal convictions may make it harder for a person to obtain employment in the place of internal relocation or they may say something about the person’s robustness and ability to adapt”. In the previous case of Sanambar, the Supreme Court seemed to think being a criminal showed positive robustness. Few if any of the Justices of the Supreme Court have experience in the criminal justice system and this Porridge-based analysis is highly questionable in the real world. Criminality often follows from vulnerability.

Lord Stephens finds that the first-tier judge had properly considered the relevant factors. Criticism by the Home Office of the judge’s finding that most employment opportunities were likely to be found in the capital was rejected as unfair given the absence of any positive evidence from the Home Office to suggest there were.

I don’t think anyone should get too excited by the idea of any reversals of burdens of proof in internal relocation cases. The point made by the court is that grounds of appeal against first-tier decisions need to consist of fair and robust criticisms. Lord Stephens pointedly quotes from Baroness Hale’s judgment in AH (Sudan), where she observed that the immigration tribunal “is an expert tribunal charged with administering a complex area of law in challenging circumstances” and held that “the ordinary courts should approach appeals from them with an appropriate degree of caution”.

Private and family life exceptions to deportation

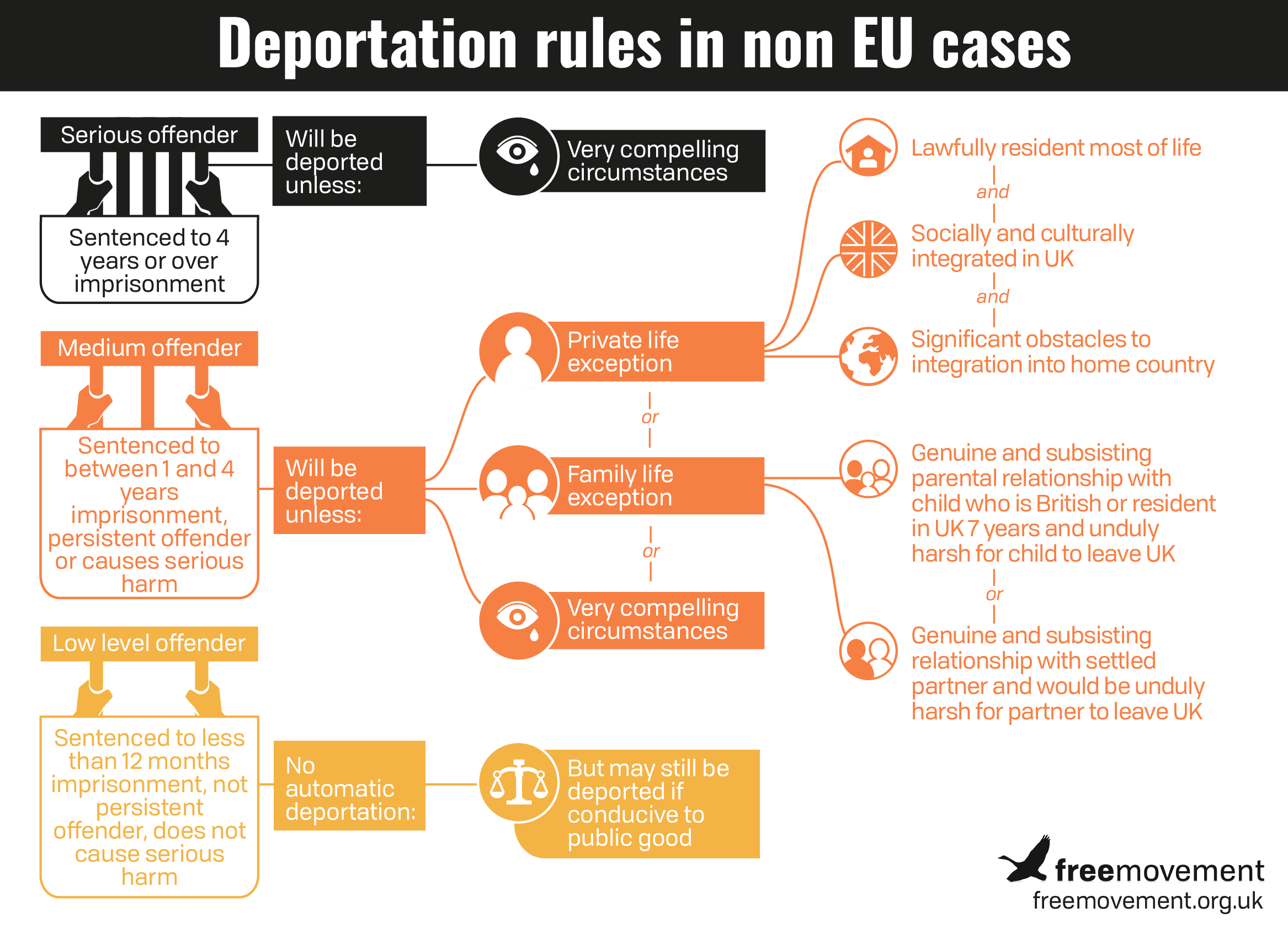

On the facts of this case, SC was what might be described as a medium-level offender within the deportation scheme established by the Immigration Act 2014 (confusingly set out in an amended Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002). He had been sentenced to a period of imprisonment between 12 months and four years.

The Supreme Court follows the approach established by the Court of Appeal in NA (Pakistan) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2016] EWCA Civ 662 which, quite frankly, re-wrote the statutory scheme. There was originally no “very compelling circumstances” exception for medium-level offenders. If anyone really thinks there was an “obvious drafting error” I have a bridge you might be interested in buying. The “very compelling circumstances” exception available to serious offenders was clearly intended to be something more than the medium level exceptions.

But the amended scheme (as reflected in the infographic above) can, just about, be read as compatible with Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights. Which makes everyone’s lives a lot easier. Notably, though, the Supreme Court relies on the Home Office concession to this effect and merely proceeds “on the basis that the decision in NA (Pakistan) is correct” (para 111).

There were therefore three potential ways SC could successfully resist deportation: the private life exception, the family life exception or by showing very compelling circumstances.

He did not qualify for the family life exception. He had, though, been lawfully resident for most of (i.e. over half) of his life. He still needed to show that he was socially and culturally integrated into the United Kingdom and that there would be significant obstacles to his integration into Jamaica.

As I have written before, the “integration” test is highly problematic given the racially charged nature of immigration control. There is a risk that, compared to white counterparts, people of colour might be judged non-integrated by predominantly white judges. Arguably, we saw this with the Akinyemi litigation, in which a 39-year-old black man literally born in the United Kingdom whose family were British citizens (he missed out on citizenship because he was born shortly after the British Nationality Act 1981 came into effect) was somehow held to be non-integrated by a series of judges. He eventually won his case on a second trip to the Court of Appeal.

The test is also in danger of falling victim to self-negating redundancy if criminality is held to mean that a person is not socially integrated. The only person who needs to rely on the test is, by definition, a criminal.

The Supreme Court avoids that pitfall by citing with approval two prior Court of Appeal judgments. In CI (Nigeria) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2019] EWCA Civ 2027, Leggatt LJ held that:

Relevant social ties obviously include relationships with friends and relatives, as well as ties formed through employment or other paid or unpaid work or through participation in communal activities. However, a person’s social identity is not defined solely by such particular relationships but is constituted at a deep level by familiarity with and participation in the shared customs, traditions, practices, beliefs, values, linguistic idioms and other local knowledge which situate a person in a society or social group and generate a sense of belonging. The importance of upbringing and education in the formation of a person’s social identity is well recognised, and its importance in the context of cases involving the article 8 rights of persons facing expulsion because of criminal offending has been recognised by the European Court.

Paragraph 58

The judge should simply have asked whether – having regard to his upbringing, education, employment history, history of criminal offending and imprisonment, relationships with family and friends, lifestyle and any other relevant factors – CI was at the time of the hearing socially and culturally integrated in the UK. The judge should not, as he appears to have done, have treated CI’s offending and imprisonment as having severed his social and cultural ties with the UK through its very nature, irrespective of its actual effects on CI’s relationships and affiliations – and then required him to demonstrate that integrative links had since been “re-formed”.

Paragraph 77

The judgment of Sales LJ, as he then was, in the case of Kamara v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2016] EWCA Civ 813 also gets the stamp of approval:

… the concept of a foreign criminal’s ‘integration’ into the country to which it is proposed that he be deported, as set out in section 117C(4)(c) and paragraph 399A, is a broad one. It is not confined to the mere ability to find a job or to sustain life while living in the other country. It is not appropriate to treat the statutory language as subject to some gloss and it will usually be sufficient for a court or tribunal simply to direct itself in the terms that Parliament has chosen to use. The idea of ‘integration’ calls for a broad evaluative judgment to be made as to whether the individual will be enough of an insider in terms of understanding how life in the society in that other country is carried on and a capacity to participate in it, so as to have a reasonable opportunity to be accepted there, to be able to operate on a day-to-day basis in that society and to build up within a reasonable time a variety of human relationships to give substance to the individual’s private or family life.

Paragraph 14

On this basis, Lord Stephens noted that membership of criminal gangs “can” tell against social integration but that it depends on the facts of the case (para 106). The first-tier judge had plainly considered past criminality in this case and there was no error of law in her conclusions. Finally, the issue of integration in Jamaica was already addressed in the context of Article 3 ECHR and for the same reasons there were clearly significant obstacles in this case.

This judgment in effect replaces and supersedes prior Court of Appeal judgments on similar issues. It stands as the key reference point on the private life exceptions to deportation within the statutory scheme.

SHARE