- BY Colin Yeo

Supreme Court finds golden visa scheme unlawful

Last week the Supreme Court found that a financing scheme to help individuals qualify for an Investor visa did not comply with the requirements of the immigration rules. The case is R (on the application of Wang) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2023] UKSC 21 and the judgment reverses the decision of the Court of Appeal, restoring the original decision by the Upper Tribunal.

The decision means that Ms Wang and over 100 others reported to have participated in the same financing scheme will not qualify for visas. The decision has little wider significance regarding the interpretation of the investor visa rules given that the whole investor programme was abolished in February 2022. Nevertheless, there will be some golden visa holders with extension applications pending or upcoming who might be affected.

It is worth stepping back to consider the judgment for two reasons. One is to highlight the problems with the design of the investor programme. The other is what we might call the “cake-ist” approach to interpretation of the immigration rules adopted by the Home Office, endorsed here by the Supreme Court.

Designing an investor programme

The broad idea of an investor programme is supposed to be that it encourages wealthy individuals to make investments in the economy of the country concerned in return for a visa. If the investments are not useful or real, all that is really happening is wealthy individuals are getting visas.

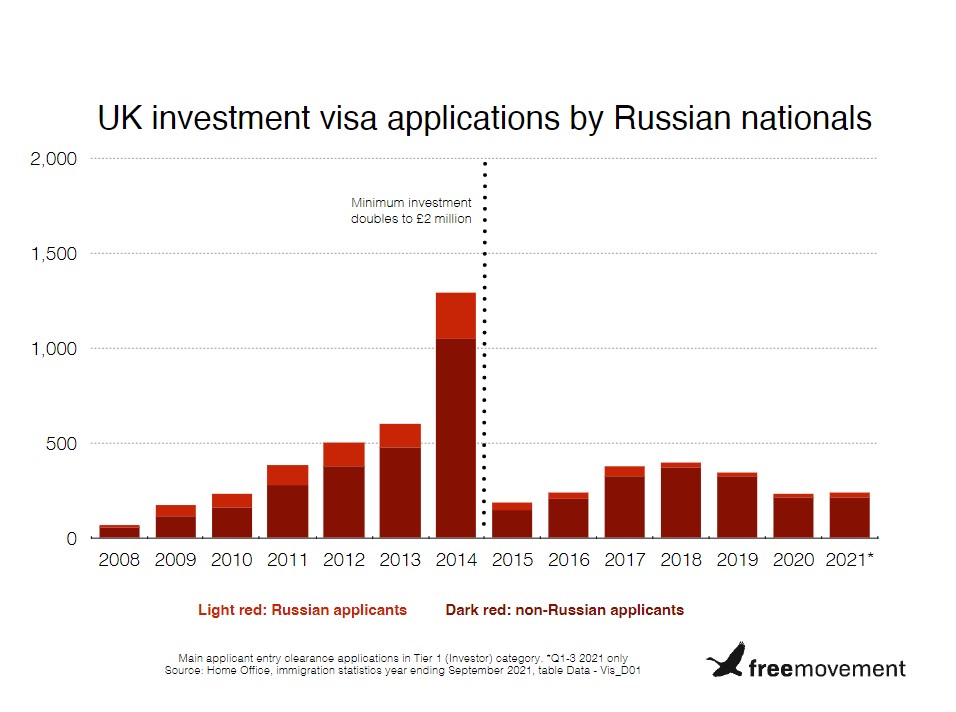

The UK investor programme launched in 1994 and went through various iterations. There was a major change of approach in 2014 which doubled the amount of investment required from £1 million to £2 million and tightened the rules to address money laundering issues.

The scheme the Supreme Court ruled in Wang did not comply with the immigration rules is referred to as the ‘Maxwell’ scheme. Calling any financial scheme ‘Maxwell’ might be considered a bit of a red flag at the outset. Essentially, investor visa applicants would borrow £1 million from Maxwell Asset Management Ltd, owned by Russian national Mr Dimitry Petrovich Kirpichenko, on the condition that it would be paid to Eclectic Capital Ltd, owned by Russian national Mrs Nika Kirpichenko. Mr and Mrs Kirpichenko were husband and wife. Once the money was passed to Eclectic Capital Ltd, it was invested in mainly Russian companies.

So, the scheme allowed someone to borrow the money, they had no choice over where it would be invested, it was passed to the wife of the owner of the first company and then it was invested in Russian companies not British ones. It clearly therefore did not meet the overall purpose of a British investment visa programme.

The court case was about whether it met the exact terms of the immigration rules, and therefore whether the rules were sufficiently well drafted to fulfil the purpose of the scheme. The Upper Tribunal held that the rules were badly drafted but good enough to achieve their purpose. The Court of Appeal disagreed, finding that the scheme did just about comply with the literal, technical requirements of the rules. The Supreme Court sided with the Upper Tribunal.

There are therefore lessons to be learned about the design of this kind of scheme, the drafting of the rules and the monitoring of compliance. There seems no immediate prospect of a similar scheme being reintroduced but the lessons go beyond just investor visas. Very careful consideration needs to be given the design and drafting of any visa type in order to avoid unintended consequences. That requires time, consultation and monitoring, none of which the Home Office seems to do very well.

Cake-ist interpretation of the immigration rules

Wang goes through the motions of citing previous authority on the interpretation of the immigration rules, referring back in particular to Mahad v Entry Clearance Officer [2009] UKSC 16 and MO (Nigeria) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2009] UKHL 25. We are reminded of the unique legal status of the rules and that they are statements of the Secretary of State’s policy, therefore not to be approached quite so strictly as conventional law.

Ms Wang’s lawyers argued that the rules constituting the points based system are rather different. Instead of reflecting broad policy through their individual words and phrases, the policy they embody is the enactment of deliberately rigid tick box requirements which produce predictable outcomes but which might cause unfairness in some cases.

Their authority for this argument was… the Home Office itself, which had been backed in a string of Court of Appeal cases.

Essentially, the Home Office has proven able to insist on a rigid tick box approach in order to refuse applications and has also proven able to insist that tick box requirements include sufficient flexibility to refuse other applications. This is why I call it a cake-ist approach to interpretation: the Home Office gets to have its cake and eat it. Displaying their normal deference to the Home Office, the courts have rolled over.

My characterisation here may be thought by some to be unfair. There may be good (if contestable) reasons for it, but there can be little doubt that the courts adopt a highly deferential approach to the Home Office. More so than in other areas of public law, I think. This is a constant but it requires the courts to adopt somewhat inconsistent approaches in individual cases.

I have been thinking recently about what I rightly or wrongly perceive to be a lack of an established discipline or school of immigration law. Immigration law is treated as an offshoot of public law yet has many unique features. We have Macdonald’s (rightly known as the practitioner’s Bible), there is the Journal of Immigration, Asylum and Nationality Law and immigration law is taught at a few universities. But if it is compared to, say, employment law, we’re miles behind. Maybe a more rigorous academic approach to immigration law might help bring some clarity of thinking to the case law in this area.

SHARE