- BY CJ McKinney

Shamima Begum loses statelessness argument against citizenship deprivation

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Shamima Begum is a citizen of Bangladesh and so would not be made stateless by being stripped of her British citizenship, the Special Immigration Appeals Commission has held. The main SIAC judgment is Shamima Begum (Preliminary Issue : Substansive) [2020] UKSIAC SC_163_2019, while there is also a brief High Court judgment refusing a linked application for judicial review: [2020] EWHC 74 (Admin).

Preliminary issue in Shamima Begum case: is she a national of Bangladesh, decided against her. Held: she is a national of Bangladesh & therefore heightened protection against deprivation of citizenship where result is statelessness does not apply. https://t.co/DROLmBu5CR

— alison harvey (@aliromah) February 7, 2020

The facts, or at any rate the allegations, of the case are well known. SIAC does not make findings about Ms Begum’s activities in Syria, her alleged links to ISIS or her risk to national security. The judgment merely records that she left the UK aged 15, went to Syria, and is now detained by Kurdish-led forces in the Al Roj camp in northern Syria.

A few days after a Times journalist found her in the camp, the Secretary of State made an order depriving Ms Begum of her British citizenship, saying that she had “aligned with ISIL [and] poses a threat to nationality security”.

Ms Begum appealed, and SIAC has now decided three “preliminary” (but vital) issues in that appeal. If any of the three issues had gone in her favour, she would likely have succeeded in overturning the deprivation order. But SIAC concluded:

(i) Decision 1 [the citizenship deprivation order] did not make A [Ms Begum] stateless.

(ii) The Secretary of State did not breach the Policy [on extra-territorial human rights] when he made Decision 1.

(iii) We accept that A cannot have an effective appeal in her current circumstances, but it does not follow that her appeal succeeds.

This was despite the court accepting that conditions in the Al Roj camp would amount to a breach of her right to protection against torture, inhuman or degrading treatment — if she could rely directly on the European Convention on Human Rights, which she cannot. Ms Begum’s solicitor, Daniel Furner of Birnberg Peirce, said that “the logic of the decision will appear baffling, accepting as it does the key underlying factual assessments of extreme danger and extreme unfairness and yet declining to provide any legal remedy”.

1. Was Shamima Begum left stateless?

This is an important question because someone who is British from birth cannot be deprived of their citizenship if they would be left stateless: section 40(4) of the British Nationality Act 1981. In effect, that means that citizenship deprivation can only be deployed against the children of immigrant parents. Those who have inherited another nationality from their parents have less protection against deprivation.

[ebook 57266]The government argued that Ms Begum, who was born in the UK to Bangladeshi parents, is a citizen of Bangladesh. Proving that is a matter of Bangladeshi nationality law, a hopelessly complicated field. Each side produced an expert witness with opposing takes on how Bangladeshi citizenship is transmitted to children of Bangladeshi heritage born outside the country’s borders.

The Home Office expert, Dr Hoque, pointed to the Citizenship Act 1951. This says that “a person born after the commencement of this Act shall be a citizen of Bangladesh by descent if his father or mother is a citizen of Bangladesh at the time of her birth”. It goes on to say that dual nationality is not permitted, so someone with another citizenship “ceases to be a citizen of Bangladesh” — but that proviso only applies to people over 21. Dr Hoque says:

Until the age of 21, therefore, a Bangladeshi citizen continues to remain a citizen alongside being a foreign citizen.

Ms Begum was, and is, younger than 21.

Ms Begum’s expert, the anonymised Witness A, disputed this analysis. His argument was partly based on a technical analysis of how the legislation is drafted and partly based on the contention that the Supreme Court of Bangladesh is so politicised that it would be likely to back the Bangladeshi government in any legal action designed to deny her citizenship of that country. Witness A

said that it was very clear to him that the Supreme Court would definitely rule in favour of the Government whatever the Government had decided was correct, regardless of what the law is.

The court confidently waded into the technical argument, pointing out that the Bangladeshi legislation was in English and is based on the common law. After exposing several “flaws” in the reasoning of Witness A, it came down in favour of Dr Hoque’s view that the 1951 law does what it says on the tin.

SIAC went on to reject the argument about Supreme Court bias, saying among other things that “we had no evidence of a case in which the Supreme Court had accepted a patently wrong argument put forward by the Government”.

2. Did the deprivation breach the Home Office’s own policy?

The court accepted that “conditions in the Al Roj camp would breach A’s rights under article 3, if article 3 applied to her case”. But “this is not a case in which articles 2 and 3 of the [European Convention on Human Rights] have extra-territorial effect”. Human rights were only relevant insofar as the Home Office has a policy which would render the deprivation decision unlawful if:

it was a foreseeable and a direct consequences of Decision 1 that there were substantial grounds for believing that A would be exposed to a real risk of ill treatment breaching the ECHR.

SIAC held that, appalling as the conditions in Al Roj may be, they were no better or worse for Ms Begum having her British citizenship taken away:

The material before the Secretary of State did not suggest that A, as a person who had been deprived of her British nationality, would be treated any differently from a British woman who had not been deprived of her British nationality but was, in other respects, in the same situation; that is, a woman who was associated with ISIL and detained by the [Syrian Democratic Forces]. A was in that situation as a result of her own choices, and of the actions of others, by not because of anything the Secretary of State had done.

3. Could Ms Begum have an “effective appeal” and did this matter?

SIAC found that Ms Begum, being trapped in a Syrian camp, “cannot play any meaningful part in her appeal, and that, to that extent, the appeal will not be fair and effective”.

Her legal team had apparently made the “assumption” that “if she cannot have a fair and effective appeal, her appeal must succeed”.

But the court did not fall prey to what it evidently regarded as touching naivety. While Parliament may have intended that “where possible, appeals against deprivation decisions should be fair and effective”, this is not a “universal rule”. Otherwise, the panel felt, all deprivation decisions could be overturned automatically whenever the person was unable to take part in an appeal against it.

It added that the structure of the relevant legislation:

shows that Parliament clearly anticipated that such appeals would often, if not regularly, be brought from outside the United Kingdom. Once that is recognised, it seems to us to follow that Parliament must also be taken to have recognised that such appeals would be brought by appellants whose circumstances outside the United Kingdom would vary in many different respects, and that some, at least, would, or might, face significant restrictions, depending on where they are when they appeal, on their ability to take part in their appeals.

SIAC also relied on Court of Appeal authority to back up this view. Despite the best effort of Ms Begum’s legal team, it found that these authorities were not displaced by the decisions in Kiarie and Byndloss [2017] UKSC 42 , AN [2010] EWCA Civ 869 or W2 and IA [2017] EWCA Civ 2146.

What now?

This is not the end of the legal process. Ms Begum’s solicitors say that SIAC will decide the question of whether she actually poses a risk to national security at a later date. Furner adds that an appeal on these preliminary findings will be launched “as a matter of exceptional urgency”.

He goes on to say:

As matters stand Ms Begum’s right to pursue an appeal against the Home Secretary’s deprivation of her citizenship has been in effect rendered meaningless.

A number of other countries dealing with similar cases, in particular of very young women, have found safe, sensible and humane ways of returning and re-integrating their citizens quietly, and with expert advice, into a normal existence. We ask that those organisations and institutions who have knowledge of successful and humane measures adopted by a number of countries urgently to contribute to the UK’s understanding of alternatives to extended legal proceedings which fail to provide swift and practical answers to such acute human predicaments as this.

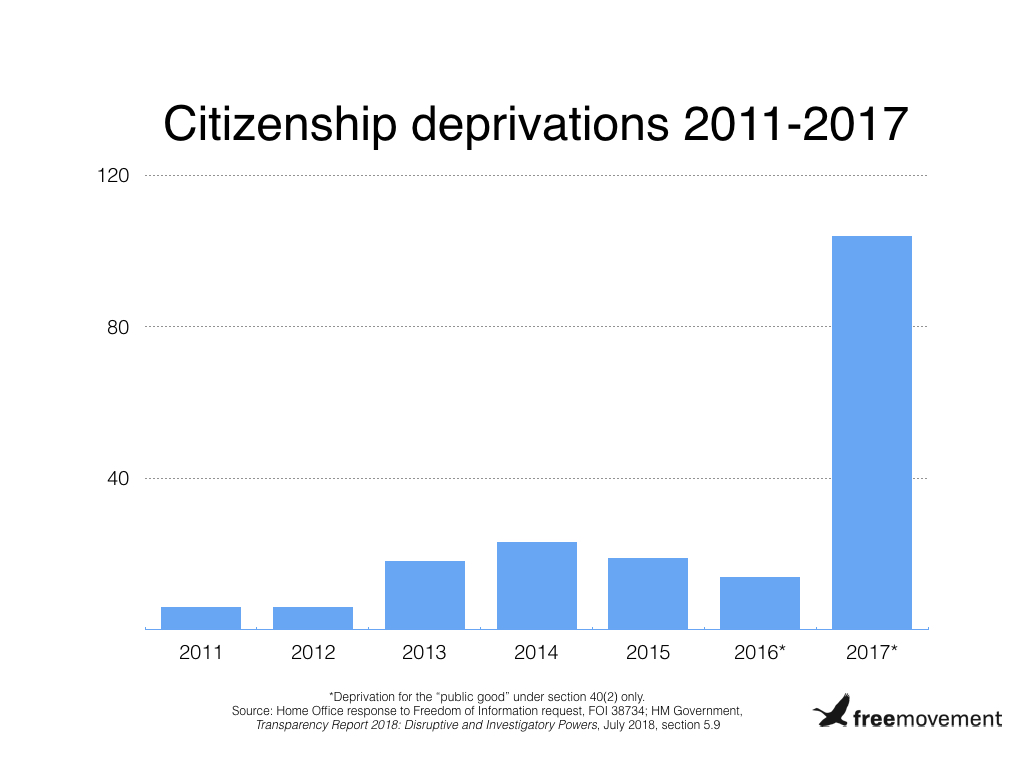

How many Shamima Begums are out there? Since 2002 the government has amended and re-amended nationality law to make deprivation of citizenship easier. Since 2010, as shown below, there has been a sharp increase in use of this amended and expanded legal power.

But we do not have up to date information. The Home Office has not published the supposedly annual report containing the number of citizenship deprivations since July 2018, and has declined to respond to either press office or Freedom of Information requests for an update.