- BY Syd Bolton

Protection deferred, protection denied? Report from Lesvos, Greece, European Union

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

The first week of September 2015. On the most northerly coast of Lesvos, one of the most easterly outposts of Greece’s many islands and a far flung outpost of the European Union, nestles the beautiful fishing port of Skala Sykaminias reached by a melting tarmac road at the end of a vertiginous series of hairpin bends, through olive and pine clad mountains, the heat perfuming the landscape with molten sap, fired earth and citrus groves. A tranquil idyll by any measurement. 6 kilometres due north, beyond a shimmering Aegean Sea the Turkish coastline can easily be seen, a blurred mirage between sky and an empty span of water. To the naked eye that is.

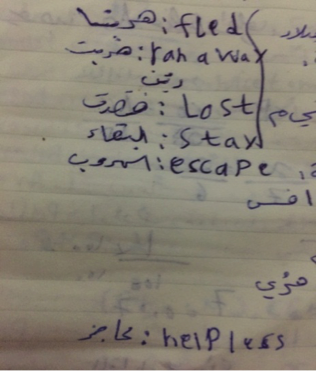

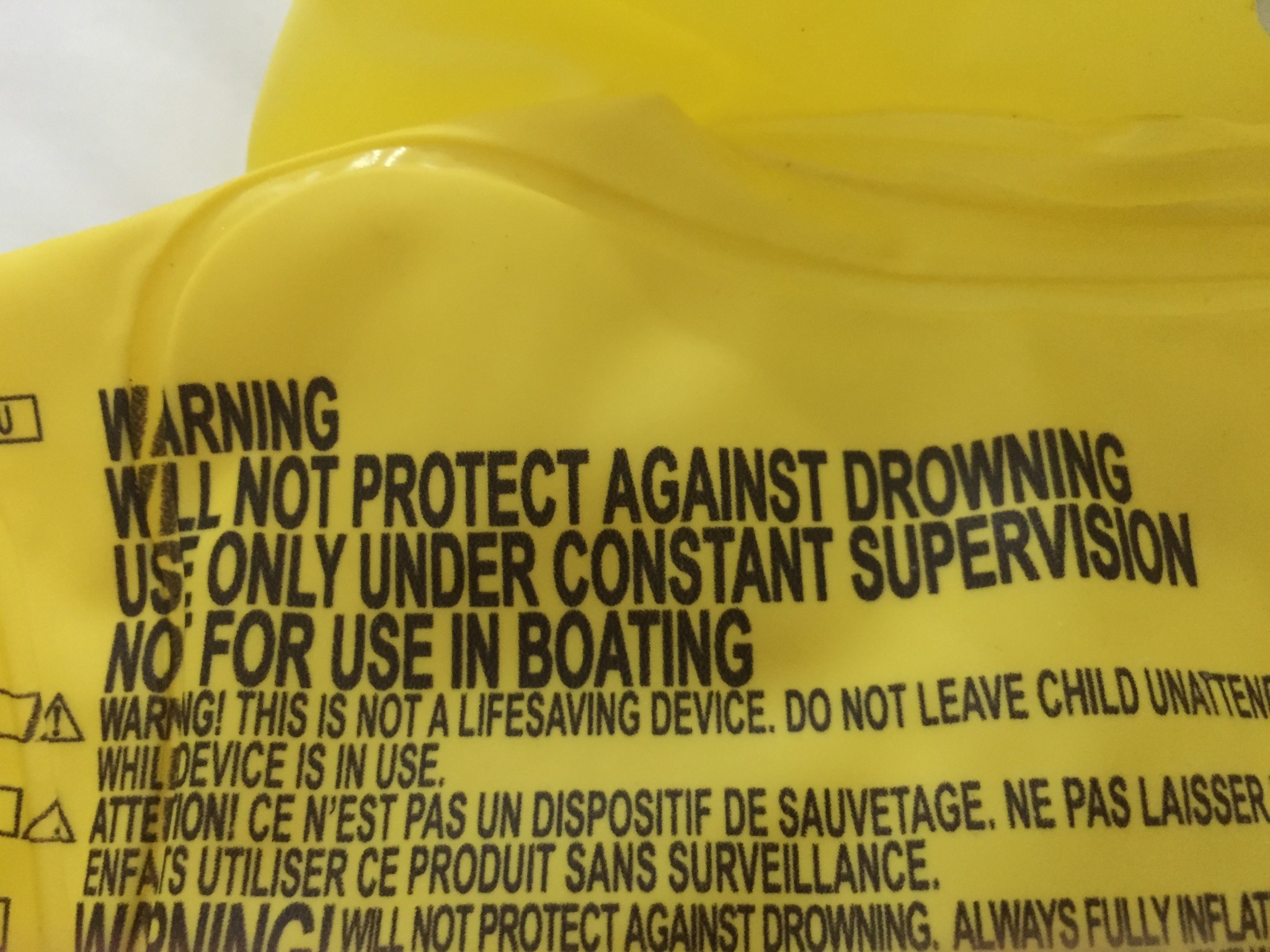

But take a closer look. All along the 20 kilometre coastline between Mithimna and Skala, a black, red, yellow and orange tideline of inflatable flotsam and jetsam litters the thin strands of rocky beach. Knife punctured rubber boats, flotation jackets and swimming pool armbands, abandoned rucksacks, strewn clothes, soaking wet children’s schoolbooks with plaintive messages.

But take a closer look. All along the 20 kilometre coastline between Mithimna and Skala, a black, red, yellow and orange tideline of inflatable flotsam and jetsam litters the thin strands of rocky beach. Knife punctured rubber boats, flotation jackets and swimming pool armbands, abandoned rucksacks, strewn clothes, soaking wet children’s schoolbooks with plaintive messages.

On the rough, unmade track above the shore, dust clouds rise behind the wheels of local first responders racing to meet the latest flotilla of human cargo. Volunteer spotters with binoculars trained far out to sea follow their movements but the untrained eye sees nothing. And then, out of seemingly thin air, one, two three, four and more black rubber dinghies start to appear, weighed down by incongruously brightly clad passengers packed 30 or more into an inflatable craft made for no more than 10. Children in mother’s arms, a teenage girl in her wheelchair, anxious fathers, families mostly. Frantic bailing of water from the boat as it barely floats to the shore.

This particular group, Syrians from Aleppo and Kobane, some young Afghani men from Kabul. All soaking wet, all cold, children shivering violently, fear in their eyes at the same moment as the fleeting euphoric relief of arrival and survival. A thousand or more continue to arrive every day this way.

The optimism of arrival is quickly tempered by reality. The absence of any official help, no accommodation, not even a place under cover to rest during the cold mountain night. An impromptu mattress of salvaged lifejackets laid out under olive trees for the lucky ones and a public water tap to drink and wash before making the arduous 2 to 3 day mountain road walk to Mytilini to ‘register’. Sykaminias’ villagers are kind and helpful compared to their Mithimnos neighbours but struggle to cope with the influx.

Local volunteers are few but heroic – an overstretched word but one which accurately describes their efforts. For many sleepless weeks they have been patrolling this 20km stretch of coast to help drag these unseaworthy vessels and their passengers ashore, saving lives, giving help night and day as refugees arrive, equipped only through donations, a rota of visiting Dutch volunteers and gifts of clothes, basic foodstuffs and short supply microfoil emergency blankets.

The local town politics of Mithimna are strongly anti-migrant and fascist elements obstruct, mislead and threaten refugee and volunteer alike. A local supermarket owner provides food, funded by donors but remains anonymous and in fear of reprisals. Another woman is too fearful to continue making sandwiches for the refugees’ journey after physical threats were made against her. The buses that arrive infrequently to take people to Mytilini to register are often turned away, prevented from using Mithimna’s terminal by obstructive town functionaries. Lucky refugees are picked up en route but most have to walk.

False maps are handed out sending refugees far the wrong way, to climb the arid volcanic mountain roads, adding a day or more to already torturous walks in 100 degree heat. Moped riding locals drive-by, fingers fake shooting at the heads of refugee children. Fascist politics makes its message very clear. A pharmacist refuses to sell medication, local doctors do not exist. It is unlawful to use scheduled public transport or use the many seaside hotels. Some taxi drivers have charged several hundred Euros for the 60km journey to Mytilini other have been generous. Tourists have been reported to hire car firms for giving lifts and their vehicle hire cancelled. (A Greek government department has at least now been tasked with investigating the exploitation of refugees on the island)

A 60km thread of refugees stretches out on a 3 day trek, babies in arms, scant possessions in heavy backpacks and wheely-suitcases. Cardboard boxes cut into sunshades provide little shade from the unyielding sun. The next destination, Mytilini Port, is already full to breaking point, no sanitation, no organisation, no shade. A long, restless queue in the midday heat to get a ticket, to join another queue, to register, to get a piece of paper, to join another queue to get a ferry ticket to Athens. Days on end of queuing and waiting. Once registered at a spasmodically open police portacabin, it’s a few more kilometres walk to wait in one of two ad hoc holding camps – Kara Tepe for Syrians, Moria for all the rest.

Some respite from the harsh terminal can be found at Kara Tepe, running water and international aid provided latrines. Some with money can buy food and bottled water from enterprising traders. Sturdier communal tents provided by an international NGO offer some brief calm for families and their children.

In Moria, there’s almost nothing and Syrian prioritisation breeds resentment and frustration. The wait to get off the island for these refugees is much longer. Scavanged olive nets and branches provide minimal shelter and little privacy amongst the rubbish and rubble, built hard up against the barbed wire and security mesh of an EU funded brand new detention centre. Empty, air conditioned and in part, used as ‘protective’ accommodation for unaccompanied children. The fear of violence at night is palpable.

Thousands continue to arrive daily at the Mytilini terminus, but the ferries have stopped taking refugee passengers for the last three days. Tensions grow and turn violent as riot police use batons and tear gas for crowd control. Ambulances arrive throughout the evening. Local fascists capitalise on the situation, adding Molotov cocktails and rifle shots to the volatile admixture of fear, anxiety, frustration and anger of the refugees trapped in the stifling and unsanitary port area.

One bright shining light exists far on the other side of town, under the deafening roar of holiday jets nestling at the bottom of Lesvos’ airport runway. PikPa, a disused holiday camp is now a safe haven for 100 of the most vulnerable refugees, especially women with new born and very young children, disabled refugees, the injured and sick. Run by local volunteers, it provides care, support and safety, restoring a little of the dignity and sanctuary stripped by the journey so far. It is a far cry from the hell-hole faced at the terminal but no less connected. Its inhabitants still have to make the long walk to the port and queue to register to get a ferry ticket if they wish to depart. One Syrian family had chosen to claim asylum and to start the slow rebuilding of their lives here at PikPa and to stay on Lesvos and had already received their refugee status and travel documents. But the overwhelming majority are compelled northwards in hope rather than expectation.

Until last week, (7th September) the Greek official stance had been apathetic at best and delinquent at worst, a dismal failure of responsibility as a 1951 Convention signatory and EU member, whatever the country’s parlous economic state. The international agencies and humanitarian aid community has been small but vital but at best inconsistent and marginal for those arriving on the shore and has failed to match the speed and scale of needs. Increasing media presence, shock tactic photos of dead children across social media and the obvious prospects of serious casualties and the collapse of any sense of order seems to have triggered a belated urgency by Greek government to try to resolve the island’s immediate pressures. By the end of last week, UNHCR was assisting the Greek authorities with basic registration processes and a large scale transportation effort had moved around 15,000 of the estimated 30,000 refugees off the island to Piraeus and then on to Athens. What conditions lie ahead it is hard to say and for how long, but with the exception of a tiny few who have claimed and received refugee protection in Lesvos their journey is almost catatonically driven towards a German, ‘Dublin-free’ promised land of safety by any means necessary.

Attempts to restrict the island’s population of refugees to 5,000 at any one time are now being implemented but still people arrive in boats in the same numbers and it remains to be seen what conditions refugees will continue to face pending relocation. New reallocation measures will do nothing to stop their need to flee or to reduce the risks of doing so. Still people risk their lives in flimsy inflatable crafts and pay fortunes to get across. Turkish coastguards are reported to have used water cannon to flood dinghies before ‘rescuing’ the passengers and towing back to the mainland. Engine thieves steal outboard motors before boats make land, watching from mopeds on cliff tops for their arrival. Or worse, privateers attack and smash engines in mid-sea, robbing savings and possessions not already jettisoned to lighten loads and bail out vessels as they flood with water. This is the shortest passage between Turkey and Greece but no less dangerous for all that.

The European Parliament’s response on 9th September was to vote in favour of a 2 year temporary measure for the emergency relocation of 26,000 refugees from Greece (and 14,000 from Italy) to be transferred to other EU member states, offering to assist and consider their asylum claims on a voluntary basis under Article 78 of the Lisbon Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. In return Greece (with EU funding) is required to improve its own asylum processes and reception conditions and the EU states’ own agency, the European Asylum Support Office (EASO) will be sent to show them how.

A 6,000 Euro per head price tag serves to encourage EU states willing to take responsibility for Greece’s new arrivals. Border patrol and enforcement operations will be intensified and greater emphasis placed on detention and forced returns of non-refugees using accelerated procedures for “white list” countries, including Turkey. A plan to relocate 120,000 more refugees and proposals for a permanent emergency relocation mechanism have also been tabled to be discussed at a meeting of EU Interior Ministers on 14th September.

These emergency arrangements do not provide immediate protection but instead push refugee responsibilities elsewhere and offer only the possibility of protection. Whilst they assist Greece in the short term (2 years) in addressing a growing humanitarian crisis the emphasis overall is on strengthening borders, increasing use of forced returns measures and accelerated procedures. It allows countries like the UK to rely on Lisbon Treaty protocols to opt out of responsibility sharing.

Registration and relocation is not refugee protection. It is a just an official ticket to somewhere else. It may be better than the images of human misery stretching across Europe on our TV channels in the last few weeks but it is not protection. Waving people through your country Austria) and applauding at football matches is of course heartening to see and infinitely better than police beatings, crawling under (Hungarian) barbed wire, being kicked by fascist journalists and packed into trains like cattle. But it is only the promise of possible protection elsewhere in Europe.

It is understandable that people are so desperate to reach Germany and other northern European destinations, given Greece’s long criticised asylum system and most recent failure to meet these challenges, though no-one was heading to the UK it seemed. UNHCR is now at least helping register new arrivals in Greece but is not carrying out refugee status determination. This is a gatekeeping exercise and the deferring of protection. By contrast the 2001 EU Temporary Protection Directive, whilst neither a panacea nor a substitute for refugee protection under the 1951 Convention, at least places protection before relocation and requires EU wide solidarity that would include the UK.

It would permit measures to evacuate rather than simply sit and wait to see who makes it across the water, running the gauntlet of vicious bandits, hostile communities and aggressive policing. It would impose equitable responsibility sharing across all EU members. It would provide protective status and resettlement with real rights, to accommodation, to education, to work and to support. Initial one year protection is extendable during or after which, refugee protection would still be available to individuals to apply for through established asylum procedures if their home countries remain too unsafe to return (for more information see Adrian Berry’s blog post on this). The proposed emergency measures place the relocation cart before the protection horse in a package that will see continued dangerous crossings and journeys, more border fences, more patrols, more detention, accelerated returns and the notable absence of the UK from EU collective responsibilities.

As this article is being written Germany closes its borders with Austria and EU Interior Ministers begin to discuss the shape of solidarity plans. Refugee protection should be at the very top of those priorities.

Syd Bolton is a lawyer specialising in working for children and refugee rights. He is currently not in practice in the UK. This article is based on a recent visit to Lesvos and the comments and views expressed are entirely his own, based on personal observation and discussion with individual refugees and volunteers in Mitilini and Mithimna on the Island of Lesvos, Greece. All legal and factual errors are entirely the author’s own.

Photographs all taken by and property of Syd Bolton August/September 2015

An article on the situation in the Calais ‘Jungle’ camp will follow shortly