- BY CJ McKinney

Offshore processing doesn’t stop the boats, Australian experts warn

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Sending asylum seekers to have their claims processed “offshore” as a deterrent to boat arrivals doesn’t work, according to Australian experts examining their own country’s experience. A policy briefing by the Kaldor Centre at the University of New South Wales, published last week, warns other countries of the “failure of offshore processing to achieve its border protection, humanitarian and foreign policy aims”. The authors may well have the UK in mind: the recently published Borders Bill “paves the way for the processing of asylum claims outside the UK”, in the government’s own words.

Offshore processing involves a deal with another country to take asylum seekers and deal with their claims for refugee status, rather than handle them yourself. In Australia’s case, asylum seekers intercepted at sea were sent to “processing centres” in Nauru and Papua New Guinea (Manus Island).

The conditions there were notorious. To give a flavour from the report (footnotes omitted):

Paediatricians reported that children transferred to Nauru were among the most traumatised they had ever seen. Medical experts working with UNHCR found the rates of mental illness offshore to be among the highest recorded in any surveyed population, and Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) similarly reported that suffering on Nauru was some of the worst it had ever encountered, including in victims of torture.

In addition to the humanitarian downsides, the briefing also focuses on the policy’s ineffectiveness from the government’s point of view.

For all that offshore processing is closely associated with Australia, the report points out that it has been many years since anyone was actually sent offshore. The system was in place between 2001 and 2008, then abandoned as an “abject policy failure”, and revived again in 2012. Although it remains official policy on paper, no offshore transfers have taken place since 2014, and since then the Australian government has been “trying unsuccessfully to extract itself from its arrangements in Nauru and PNG”.

The purpose of offshore processing is deterrence. There is no point in making a dangerous journey to Australia if you’ll end up rotting in some other country entirely, goes the reasoning. The researchers found no evidence of this working:

During the first phase (13 August 2012–18 July 2013), when offshore processing was implemented with the possibility of (deferred) settlement in Australia for people found to be refugees, more than 24,000 asylum seekers arrived in Australia by boat. This number was considerably more than at any other time since the 1970s, when boats of asylum seekers were first recorded in Australia. Moreover, as the months passed, and news of the policy presumably reached some of those who were contemplating travelling by sea to Australia, there was no noticeable change in the rate of arrivals…

While the number of boats reaching Australia has fallen sharply since 2014, the report puts this down to a switch to stopping boats out at sea and forcing them to turn around. In other words, the drop in arrivals coincided with the abandonment of the offshore processing policy.

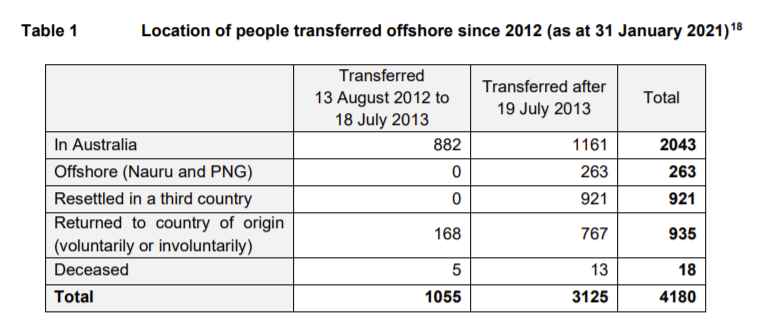

Of the 4,000 or so unfortunate souls dumped on Nauru or Manus Island between 2012 and 2014, around half ended up in Australia anyway. Over the years they were “exposed to such extreme harm” that, by 2019, the Australian government was “forced to medically evacuate” the remaining detainees. A couple of thousand were eventually relocated elsewhere: a pretty poor return given the financial, diplomatic, reputational and human cost.

Nor has locating the processing centres out of jurisdiction enabled the Australian state to avoid legal liability for conditions there:

In fact, at times, the offshore processing policy created additional legal difficulties for Australia in that its legal obligations continued, but its capacity to fulfil them was complicated by the involvement of other sovereign States. Australian courts have declined to relieve the government of its duties to people offshore on this basis.

The report concludes that offshore processing failed to achieve any of its goals. It did not deter boat journeys, nor save lives at sea, nor “break the business model” of people smugglers. Worth bearing in mind, then, should the Home Office pursue a similar policy in the name of those same objectives.

One Response