- BY CSEL

Myth buster: “memories of trauma are engraved on the brain”

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Table of Contents

Toggle“I’ll never forget that day”

We tend to believe that the more important an experience, the more likely it is that it will be ‘engraved’ on the brain. In the asylum system, this is maintained by decision makers who maintain the belief that a genuine victim of trauma will be particularly able to recall the traumatic event.

Why do we think this?

Firstly – many of us have very clear pictures of where we were and what we were doing at moments of hearing shocking news. A number of research studies have examined these ‘flashbulb memories’ where people are asked about their memories of shocking public events, such as the shooting of John F Kennedy in the US[1], or the death of Princess Diana in the UK[2].

However, these incidents, whilst perhaps shocking, are hardly traumatic, in that they present no threat to our lives or physical integrity, so extrapolating from that research, and our personal experiences of such events, to traumatic experiences, is misleading. Also – we usually share these experiences widely with our friends & others, repeating and elaborating them, and so making them better remembered.

But also – when it comes to truly traumatic experiences, some parts of the memory are held, very fixed, in memory. The Dual Representation Theory of traumatic memory explains this.

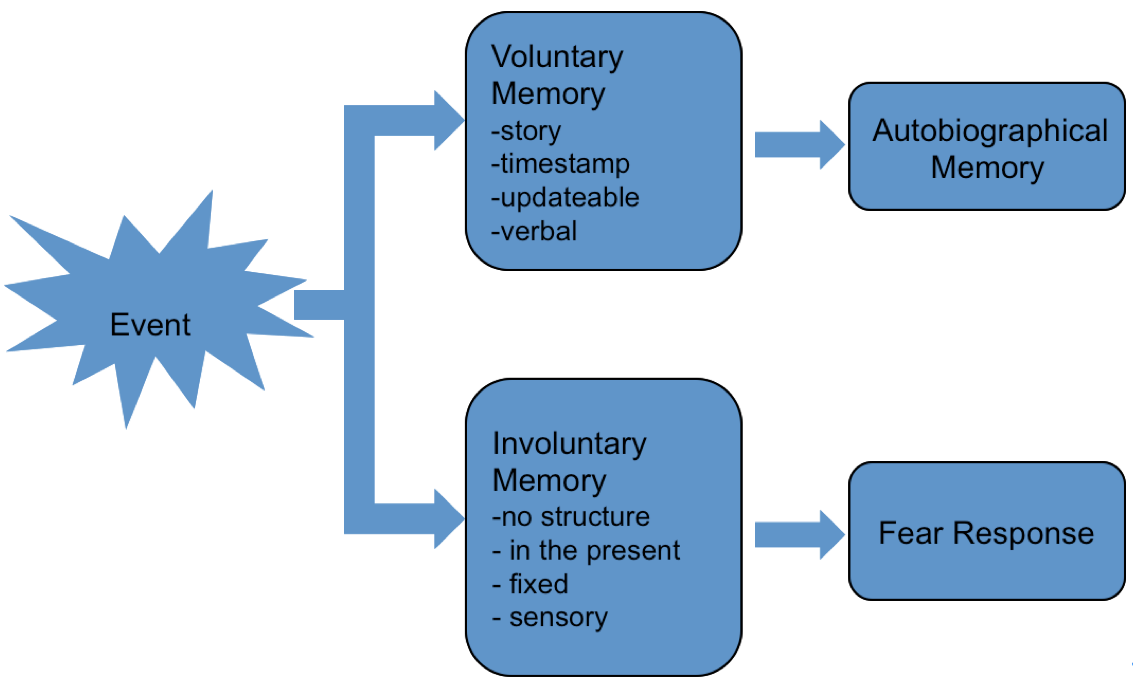

The Dual Representation Theory of traumatic memory[3] describes how we remember normal and traumatic events differently:

Normal memories, as we saw in the first Myth buster, are constructed, voluntary narratives about the past, and can be updated according to the needs of the conversation in the present.

Traumatic memories, on the other hand are vivid, sensory memories; fixed moments that are triggered by scenes or contexts that are similar to the traumatic event, or physical or emotional feelings that were evoked at the time of the traumatic event. It makes sense if you think that these are life-threatening events, where we need to assess only the key information, in order to act quickly. For example people describe very fixed images – the sight of the ground close to their face – and this comes back to them whenever they are reminded of the event, and evokes an emotional and physiological fear response – for example tension in the muscles (the body’s preparation for running away or fighting back).

So when we talk about memories for traumatic events, we may be confusing two, very different types of memory. Involuntary memories are indeed fixed, and less likely to change.

The kind of memory that is required to make a credible asylum claim is not the distressing, fixed ‘snapshots’ of moments of the trauma. People are asked to explain in words, in a reasonably coherent narrative, what happened – a normal, autobiographical memory (the ‘voluntary memories’ in the diagram above). They may not be able to deliver this narrative. However, when asked to describe experiences of persecution, traumatic, ‘involuntary’ memories may be evoked.

What does the research show?

As an interviewer it is not always clear when someone’s involuntary memories are being triggered. But the following study shows that the type of information elicited will be quite different, depending on which kind of memory is being evoked by questioning.

Sixty-two people meeting diagnostic criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder completed a detailed written account of a traumatic experience. Afterwards they identified the sections in the narrative when they had been having a ‘flashback’ – or triggered traumatic (‘involuntary’) memory. The researchers were then able to compare the sections of the written account describing normal autobiographical memories from those describing the traumatic memories. Traumatic, involuntary memory periods were characterised by greater use of detail, particularly perceptual detail, by more mentions of death, more use of the present tense, and more mention of fear, helplessness, and horror, compared to the voluntary (normal) memories[4].

This shows that, whilst these trauma memories might stay fixed in the mind, trying to produce a coherent narrative of a traumatic experience when traumatic memories – sights sounds and smells, thoughts of death, reliving the moment – are being evoked, will likely be very difficult for the interviewee.

Moreover

Some people respond to reminders of traumatic experiences – also called Triggers – by dissociating. This can be imagined as a very powerful (and usually unpleasant), extreme form of day-dreaming; the person loses contact with the here and now. It is not under the person’s conscious control. It might be either a protective response to overwhelming distress in the current situation (for example, a distressing interview or court hearing), or it may be a reliving of the traumatic event itself (a ‘dissociative flashback’). Both mean that the person is not aware, to a greater or lesser extent, of their current surroundings and this can leave them disoriented and confused. Sometimes they will have no memory of what has occurred previous to the dissociation.

A study by Diana Bogner and colleagues[5] asked 27 refugees and asylum seekers to rate on a standardised (tested and widely used) questionnaire the extent to which they had been dissociated in their substantive interviews with the Home Office. They were rating their experience some time after the event, so this is only an approximate indication, but the majority of participants indicated a ‘clinically significant’ score on this scale – suggesting high levels of dissociation in asylum interviews. As an illustration of the effects of dissociation one of the study participants commented:

“I tried to talk, but my mind kept wandering off and I kept thinking about the trauma and my family that I lost. Everything seemed unreal to me, I felt like I was dreaming. I found it hard to focus on the interview and answer questions” [6]

Even in the UK, where there is a lot of public awareness of the effects of traumatic experiences, people struggling after traumatic events often do not have a good understanding of what they are finding difficult and why. A very common response when post-traumatic stress is explained in a clinical setting is “so I’m not going mad?”. People experience a wide range of difficulties after traumatic experiences, and for asylum seekers these will be in addition to the range of experiences involved in leaving and travelling to a new country, so they may not be able to give a reasonable explanation of their difficulties, nor even articulate them very clearly. Furthermore not being able to present oneself clearly may be shameful for some people, and in many cultures, mental health difficulties are taboo.

What have we learned?

If interviews are intended to obtain the best evidence possible on which to decide eligibility for international protection, interviewers need to take care

- To be aware that their questions may invoke either normal (voluntary) or traumatic (involuntary) memories

- That traumatic memories may cause dissociation

- That, once dissociated, the interviewee is less able to access their narrative account (autobiographical memory)

- That interviews should not continue until the interviewer is assured (by the interviewee) that they are aware of their surroundings, fully engaged with interview, able to concentrate and

- Interviewees may or may not be able to articulate their difficulties to the interviewer and may need help with this.

[1] See Brown, R. & Kulik, J. (1977). Flashbulb memories . Cognition 5(1) 73-99

[2] Hornstein, S. L., Brown, A. S., & Mulligan, N. W. (2003 ). Long-term flashbulb memory for learning of Princess Diana’s death. Memory, 11(3), 293-306

[3] Brewin, C.R., Dalgleish, T. & Joseph, S. (1996) A Dual representation Theory of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. Psychological Review, 103(4), 670-686; Brewin, C., Gregory, J. D., Lipton, M., & Burgess, N. (2010). Intrusive images in psychological disorders: characteristics, neural mechanisms and treatment implications. Psychological Review, 117(1), 210-232.

[4] Hellawell, S. J., & Brewin, C. R. (2004). A comparison of flashbacks and ordinary autobiographical memories of trauma: content and language Behaviour Research and Therapy, 42(1), 1-12

[5]Bogner, D., Herlihy, J. and Brewin, C. (2007). The impact of sexual violence on disclosure during Home Office interviews. British Journal of Psychiatry 191 pp.75-81

[6] Bögner, D., Herlihy, J., & Brewin, C. (2007). Impact of sexual violence on disclosure during Home Office interviews. British Journal of Psychiatry, 191, p.78