- BY CJ McKinney

Is the tide turning on media coverage of migrants?

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Yesterday afternoon, the Home Affairs committee of MPs had before it a selection of the nation’s newspaper editors. The subject of questioning: “whether there is an issue with treatment of minority groups in the print media”. Anyone who has glanced at the headlines about immigration over the past decade or so will know why the question was asked.

Visual reminder of how immigration played in Leave camp narrative.34 front pages this yr compiled by @gameoldgirl pic.twitter.com/tW6iUBGhz5

— Kim Ghattas (@KimGhattas) June 26, 2016

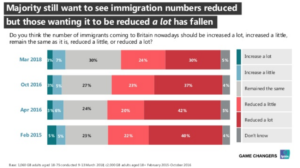

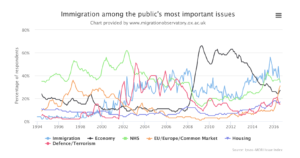

Most British people think that immigration is too high. The proportion who think that “there are too many immigrants in Britain” has been well over 50% for decades, according to research by Ipsos MORI. As many as three quarters of British people want to see immigration reduced. And while something can be unpopular while also being unimportant, immigration has been consistently named in surveys as among the most important issues facing Britain, as the chart below from the Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford shows.

It is true that attitudes have started to shift since Brexit. But at least some of this softening in public hostility to immigration can be put down to short-term satisfaction with a referendum vote predicated on tighter borders. Whether the long-term trend is toward a more welcoming nation remains to be seen.

Rivers of ink

While there are plenty of factors shaping attitudes to migration — from overt, Enoch Powell-style racism to the actual number of immigrants at any given time — the media is obviously a major influence. Ipsos MORI points out the following result from a 2005 study:

newspaper readership is much more likely to be significantly related to concern about immigration, after controlling for other demographic differences, than any other issue measured (including health services, defence/terrorism, education and crime). Indeed, the four most important predictors of concern about immigration were all whether people read particular newspapers.

The picture has changed somewhat since, and the link was never direct. “This still does not prove a causal effect”, the researchers points out, as “people partly choose newspapers that reflect their already formed views”. But few would deny that the media is an important factor in how people think of immigrants.

The Migration Observatory has been studying how immigration is depicted in print newspapers for over a decade. The results, no less than the articles themselves, make for depressing reading. It has found that, for example, that between 2010 and 2012

The most common descriptor for the word IMMIGRANTS across all newspaper types [was] ILLEGAL.

Another study showed that

‘Mass’ was the single most common way of describing immigration from 2006 to 2015.

Liz Gerard, editor of the SubScribe journalism website, displays the results of her own research in this area more visually: her montages of front page immigration coverage have been used as part of a museum exhibit (shown below).

Ms Gerard counted 288 front pages devoted to immigration in 2016 alone, with “a marked increase immediately before the referendum”. More than half were accounted for by the Daily Express or Daily Mail. That year, those two newspapers contained 1,768 pages on which a story on immigration, race relations or the treatment of foreigners featured.

Unsurprisingly, these stories were “overwhelmingly negative”.

Things can only get better

But there is cause for optimism. Some commentators are beginning to see green shoots emerging from beneath the blanket negative coverage.

Is This the End of Britain’s Obsession with Immigration?, Vice asked in January, noting that the issue has fallen way down the list of public concerns as recorded by Ipsos. Charlie Beckett, director of the POLIS media think-tank at the LSE, told the magazine that:

Stories like ‘immigrants kill the Queen’s swans’ in the Daily Star seem to have disappeared. Tabloids don’t feel a lot of traction with those stories because, if anything, the story around immigration is nearly the opposite now – it’s fruit farmers saying ‘we don’t have enough people'”.

Ms Gerard’s figures bear this impression out. With the referendum won, she says, immigration-related front pages dropped from close to 300 in 2016 to 97 last year. So far this year, there have been only 25, “and the Windrush scandal has tilted the balance from negative to positive”.

This relatively chilled mood even extends to the notoriously hysterical Daily Express, which is now under new management. “In the seven weeks since the takeover, the word ‘migrant’ has appeared in 23 news stories, against 49 in the previous seven weeks”, Ms Gerard reckons. Yesterday at the Home Affairs committee, the new editor sought to distance himself from the “downright offensive” splashes of the recent past.

While this softening of media hostility was discernible before the Windrush scandal came to a head last week, it is seen as a potential tipping point. The widespread outrage from across the political spectrum at the treatment of elderly Commonwealth residents has “demonstrated to liberals how to better make the case for immigration”, writes George Eaton in the New Statesman. “When immigration is given a human form, support for it increases”.

The notion that people are more welcoming of individual migrants than a faceless, statistical swarm emerges consistently from the academic and journalistic research. So too does the fact that, when pressed on which migrants should be excluded from an already restrictive system, people tend to be less doctrinaire about shutting up shop.

From the National Conversation on Immigration to the BBC’s Nick Robinson tackling voters on the streets of Mansfield, evidence abounds that the public is open to persuasion on the merits. “British voters are very responsive to the details of migration – who is coming, why and what they bring”, as Dr Rob Ford has put it.

What is to be done?

So, to reiterate an old saw, positive stories about migration and its benefits are worth telling. What the Commonwealth migrants debacle has shown is that evidence about the negative impact of the crass, restrictive policies needed to enforce strict controls also rings out.

Young migrants who've had UK schooling face higher tuition fees as applying for citizenship is too much for some like Michelle, whose mum had to choose between her & her sister. @nadhimzahawi argues support for students is more than when his family migrated. #r4today @LetUs_Learn pic.twitter.com/1kZ6970NVe

— BBC Radio 4 Today (@BBCr4today) April 25, 2018

Immigration lawyers, who see the human impact of migration policy every day, know that the Windrush stories form only the tip of the iceberg. Nor is the underlying cause of that debacle — Theresa May’s “hostile environment” — the only recent immigration policy to ruin lives. Consider the following examples:

- Highly restrictive rules on “adult dependent relatives” attempting to join their UK-based family — leading to cases such as the 92-year-old widow packed off to South Africa despite having no remaining family there.

- The minimum income requirement to bring a non-EU husband or wife to live in Britain — leading to cases such as the young married couple forced to live apart for three years and an estimated 15,000 “Skype families“in which children are separated from one of their parents.

- The rigid quota on visas for skilled non-EU workers — leaving the NHS unable to recruit doctors from overseas.

- Charging over £1,000 to register a child as British when the actual administrative cost to the Home Office is £372 — leading to cases such as the 10-year-old girl removed from the UK for inability to pay for the citizenship she was legally entitled to.

- Demanding that children attempting to register their British citizenship be of “good character” — leading to hundreds of under-18s being refused citizenship.

- The lack of any administrative flexibility — leading to cases like the GP facing removal for submitting his application to stay in the UK 18 days late.

From a legal point of view, these and other immigration policies are ripe for public interest legal challenges of the kind in which the AIRE Centre and Good Law Project specialise.

In the meantime, the fact that most have given rise to sympathetic media coverage of individual hardship should give supporters of a humane immigration policy cause for optimism. Brexit may look increasingly like a done deal, but the future of Britain as an open, welcoming country is still in the balance.

Thanks for Liz Gerard for the newspaper montage that illustrates this article, as well as for the data on recent immigration coverage mentioned above.