- BY Nath Gbikpi

How can a man with Asperger syndrome who grew up in Britain be deported?

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

How can a young man with Asperger syndrome and poor mental health, who has lived in the UK for the overwhelming majority of his life, be deported to Jamaica?

The Voice newspaper reports on the case of Osime Brown, a 21-year-old man who the Home Office is trying to deport. I do not have all of the details, but the facts as reported by The Voice are really quite stark. Osime arrived in the UK aged three to join his mother and three older siblings. He has lived in social care since 2014, and has been clinically diagnosed with Asperger syndrome.

Osime has the mental capacity of a five- or six-year-old child. There is photographic evidence of him self-harming since 2016, he suffers from high anxiety and depression, and attempted to commit suicide earlier this year. During a recent hospital visit, Osime was fitted with a pacemaker and a device to monitor his regular doubts of dizziness.

His siblings say that:

We are scared that he is going to end up dead as he is so trusting and does not understand the culture [in Jamaica] or the people’s nature.

Despite all of this, the Home Office is trying to deport him, and the First-Tier Tribunal dismissed his appeal against the deportation order. A further appeal hearing took place at the Upper Tribunal on 28 February and a decision is pending.

Why might a judge allow him to be deported?

The answer lies in the length of Osime’s sentence. According to The Voice, he has committed a series of offences which culminated in a sentence of five years in a Young Offender Institution. Although youth detention is not technically “imprisonment”, the courts have held that it essentially amounts to the same thing in the context of deportation.

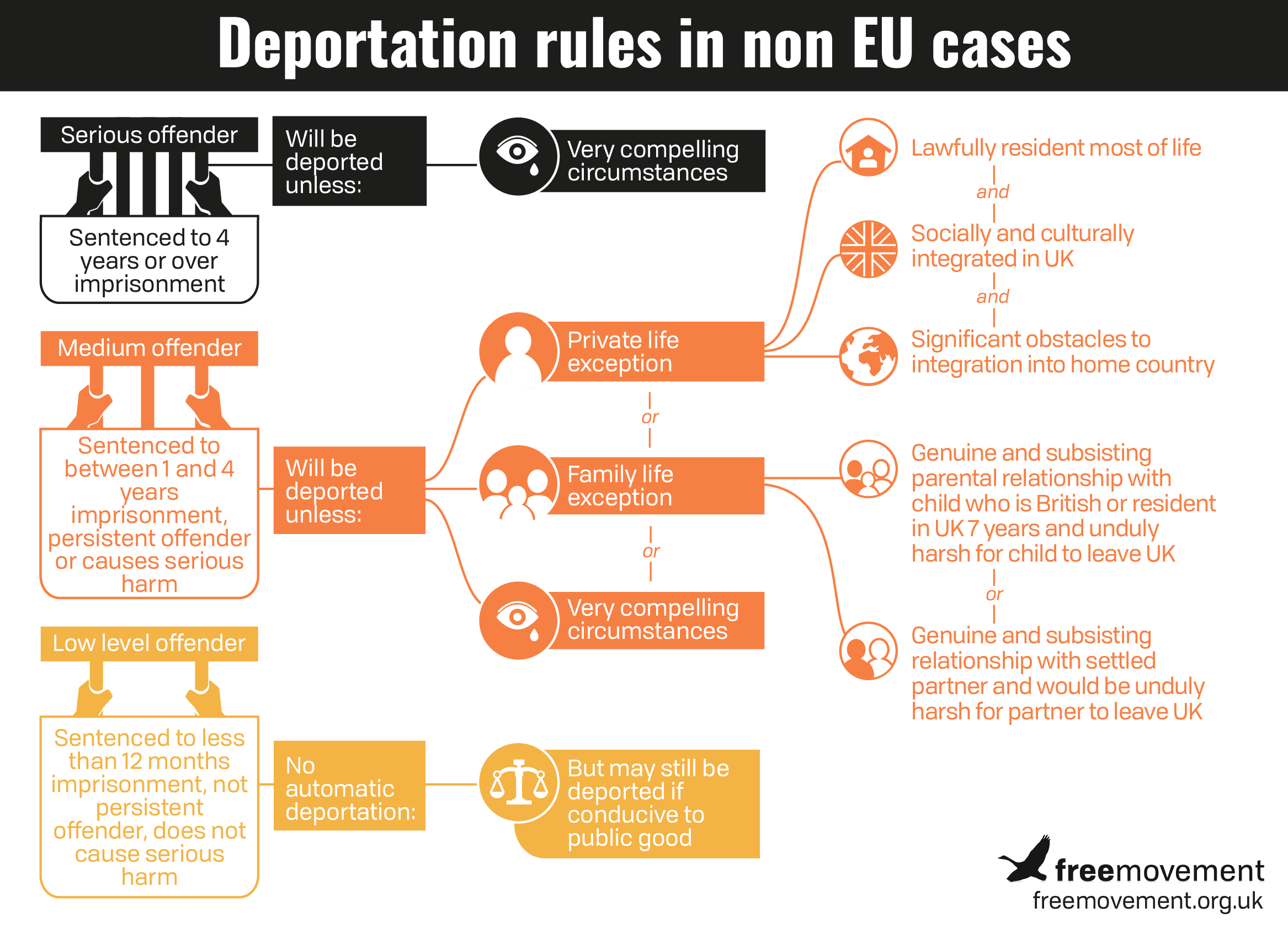

Because he has been sentenced to more than four years, to successfully appeal Osime would need to show that there are “very compelling circumstances” in his case which would “outweigh the public interest” in deporting him.

Home Office guidance calls this an “extremely high threshold”. It seems that neither the Home Office nor the First-Tier Tribunal were satisfied that the very compelling circumstances test is met in Osime’s case.

Mental illness or lack of capacity not necessarily “very compelling”

Having a disability or poor mental health are factors relevant to the test of whether there are very compelling circumstances, but do not constitute a trump card.

Severe mental health problems can prevent a person from being deported but only if they are subject to certain orders under the Mental Health Act 1983 (section 33(6) of the UK Borders Act 2007). Even then, this would only mean that the person would not be automatically deported: they could still be deported if the Home Office deemed it conducive to the public good.

Some appeals against deportation on the basis of mental illness or disorders have succeeded. For example, in the case of KE (Nigeria) [2017] EWCA Civ 382, the Court of Appeal found that there were very compelling circumstances in the case of a man with schizophrenia:

the Respondent has not only fully integrated here, he has been here since he was 11 years old (he is now 37); the relevant offending resulted from his mental illness, namely paranoid schizophrenia; that illness is now controlled here, such that reoffending is unlikely; he has no relations or other support in Nigeria; without any support there, he will be unable to cope there and it is extremely likely that he will not have access to medication which will keep his paranoid schizophrenia in check; and, as a result, in a very real way, deportation would rob him of any sensible private life.

In the case of El Gazzaz [2018] EWCA Civ 532, on the other hand, the same court upheld the decision to deport Mr El Gazzaz despite him having been assessed as unfit to give evidence in the First-Tier Tribunal and unfit to plead during his trial for a firearm offence. Although Mr El Gazzaz was suffering from serious mental ill-health, among the reasons his case failed was the fact that he could access healthcare in Egypt when deported there.

Double punishment

More broadly, Osime’s case shows how inhumane the rules around deportation are. If deported, Osime will effectively be doubly punished: first for having a committed an offence, and second for not being a British citizen.

As Colin recently highlighted following a controversial charter flight to Jamaica, deportation law hasn’t always been as cruel as it is today. It can and should be changed to bring back some humanity into the decision-making process.

This article was updated on the day of publication to include some additional details of the case and a photograph of Osime Brown. Our thanks to Veron Graham of The Voice for providing these.