- BY Colin Yeo

Free Movement review of the year 2021

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Since 2013 I’ve been trying to stand back at the end of each year, take a look back at the previous year and look ahead to the next. Last year I picked out the coronavirus, the Brexit fallout and refugees as themes for the coming year.

Immigration law

It hasn’t been an unusually terrible year for immigration law. The speed of change has perhaps slowed a little. There were five Statements of Changes to the Immigration Rules in 2021, although four of those landed in just the last three months.

The ‘tiers’ of the posts based system disappeared. With their implications of hierarchy of importance and value these will be unlamented, but they did at least provide some semblance of structure. The flurry of employer-led work visas announced in the autumn, culminating in a major new one for the care industry on 24 December 2021, caused some amusement at Free Movement Towers. Every time, some spokesperson would claim “you’ve been bad this year, no more new visas for you!” Every time, another new visa was announced.

We have seen no serious attempts at reform of immigration law or policy. The simplification project seems to have petered out, with new sets of rules barely improving on old ones. The causes of the complexity remain unaddressed: daft substantive requirements, pseudo-automation of decision-making and micro-management of migrants.

We’ve seen, I think, seven Supreme Court decisions on various immigration issues. This includes the Shamima Begum case on citizenship deprivation, G v G on the interaction of child abduction and asylum claims, Sanambar on the deportation of a man who entered the UK aged 9, BF (Eritrea) and R (A) on age assessment policy and the correct approach to judicial review of government policies generally, TN (Vietnam) on review of old fast track decisions, Majera on immigration bail and the need to object court orders even where they are invalid and Fratila on benefits and pre-settled status. There are more Supreme Court decisions to come in 2022, with judgment awaited in the case challenging the high fees for children to register as British and permission just being granted in two key deportation cases.

Refugees

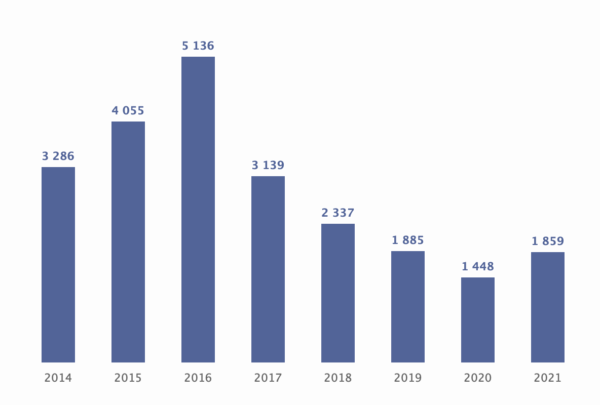

It’s been an outright terrible year for asylum law and policy. The number of refugees dying in their attempts to reach safety actually increased last year. These figures are for the Mediterranean routes:

A further 766 have died on journeys within Europe, again since 2014, which includes an estimated 194 attempting to reach the United Kingdom from mainland Europe.

Last year I wrote that “in the absence of any replacement to Dublin, the impossibility of removing refugees who arrive by small boat to France or elsewhere is going to be politically problematic for the government. We can expect politicians to look for other ways to perform in public their hostility to small boat arrivals.” That has certainly come to pass.

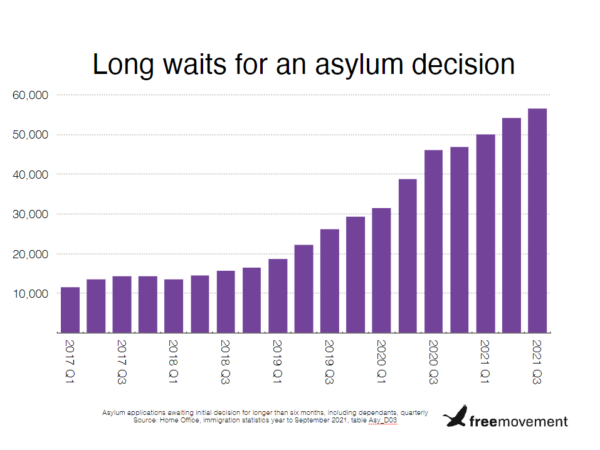

New inadmissibility rules were due to commence on 1 January 2021. I said that massive delays were already a problem in asylum cases and the new rules were going to make the situation much, much worse. “This sets up a vicious circle,” I wrote. “Even harsher measures are then called for to deal with the problems created by previous counter-productive cruelty.” I wasn’t wrong, sadly.

The delays are terrible for refugees, who are forced to endure prolonged destitution and inactivity as a form of deliberate punishment for claiming asylum in our country. The justification given is that this will somehow deter others from doing likewise. But it doesn’t. And well over half of those penalised in this way will be granted asylum. Even those who lose their cases are tacitly permitted to remain long term, with removal of failed asylum seekers at historically low levels.

The delays are also terrible for the British public. The initial treatment of refugees causes them permanent disadvantage as they begin new lives here, which is bad for all of us. The delays have substantially increased asylum support costs. And removal of a person who will ultimately lose their asylum claim become much, much harder and crueler the longer they stay.

The big picture

This will seem counter-intuitive to many readers, but there is an argument to be made that the asylum system is much better for refugees now, at the end of 2021, than it was prior to 2010.

The success rate for asylum claims has crept up over the last decade. Around half of those who claim asylum will now receive asylum from the Home Office at first asking and a further half of those who appeal will win their cases. This is a testament to the work of many campaigners, to UNHCR and to serious-minded Home Office managers and staff. Claims based on sexuality and religion are dealt with more respectfully than in the past, although perhaps that is not saying very much. While decision making could no doubt be further improved and it is not hard to find poorly reasoned asylum refusal letters, the ‘culture of disbelief’ is nothing like it once was. Barristers and country experts should remember that the cases we see are the ones that are refused; we never witness the successful cases.

The number of detention centres and detention spaces has fallen; asylum seekers are far less likely to be detained than they once were. The unfair detained fast track was abandoned in 2015 and at the time of writing had not yet been reintroduced. The number of asylum removals is at its lowest level for over twenty years, at perhaps around 1,000 per year: failed asylum seekers are considerably less likely to be forcibly removed from the UK than in the past. At least, I think that is so. The increase in the proportion of successful cases also needs to be taken into account.

And the refugee resettlement scheme first launched by David Blunkett back in 2002 or so was expanded massively in 2015. It looks like it is being expanded further, although it is hard to tell with the fudging of figures.

There remain major problems with the asylum system, though. The stand out issue, in my own view, is the increasing level of delay. This is due to Home Office internal management, not the efficient appeal process or small number of fresh claims. Asylum seekers are often waiting well over a year for a decision on their initial claim for asylum. Forcing them to live on destitution-level asylum support payments in squalid accommodation for even a short time would be bad enough. It is utterly indefensible for prolonged periods, particularly when well over half will ultimately win their cases. The justification given is that this will somehow deter others from following in their footsteps. But it doesn’t. Anyway, even those who lose their cases are tacitly permitted to remain long term. The delays make it both harder and harsher to remove those whose cases ultimately fail.

Speaking for myself, I am not sure that the apparent decline in removal of unsuccessful asylum seekers is something to be celebrated. In a functioning asylum system, those whose cases fail will have to leave the country. There is no point in having an asylum system if this is not so. It is hard for anyone to have any faith in a pointless process. At the moment, though, the Home Office cuts off an asylum seeker’s support and simply hopes they will leave of their own accord, relying on hostile environment policies to make their lives so intolerable that they ‘self deport’. There’s no evidence to suggest this works. But it does give rise to an underclass of unauthorised residents living their lives outside the protection of the law.

This points to other problems in the asylum system. The levels of support provided to asylum seekers have barely increased in years, meaning they have fallen even further in real terms. There is no meaningful integration strategy for recognised refugees. Treatment of refugee children is abysmal in multiple ways, including additional delays, hostile age assessments and denial of family reunion rights.

And the dramatic increase in small boat crossings is clearly a major problem. Initially, it looked like this was largely a change of route of entry rather than an overall rise in the number of people claiming asylum. But the latest figures suggest there has been a fairly steep overall increase. It was hardly safe to travel to the UK by lorry but the journey in an inflatable dinghy on the face of it seems far more dangerous. The government has no meaningful response at all to this phenomenon.

These improvements are all reversible. Waiting times can get worse. Fast track processes can be reintroduced and decision-makers can become careless again. As well as asylum seekers being badly treated, recognised refugees might find themselves not just ignored but penalised. Which leads us to…

Nationality and Borders Bill

The biggest immigration law event of next year will be the passing into law of the Nationality and Borders Bill. It has already passed the Commons and now needs to work its way through the Lords. Best guesses are that it will become an Act of Parliament in maybe February or March 2022.

There are some positive aspects of the legislation. The early clauses address and correct historic nationality law injustices.

But most of it is highly regressive. Or, at least, it would be if implemented. It looks like an attempt to undermine or reverse the positive aspects of the contemporary asylum system.

The removal of refugees to some other country to deal with depends on finding some other country. Prosecuting, convicting and imprisoning virtually every refugee arriving in the UK would become possible in theory, but it is hard to believe it will happen in reality, not least because of the resources required to carry that through. The statutory authorisation to create a two-tier asylum system may or may not be implemented in practice. The proposal to remove a right to work from recognised refugees would clearly and unambiguously breach the terms of the Refugee Convention (see Article 17) and I still find it hard to believe a British government would do that. Evade and avoid, yes. Breach, no. Time will tell.

Patel, her advisers and the Home Office as an institution seem to have staked their political credibility on reducing small boat crossings. Given there is no evidence that deterrent measures have any effect on the destination preferences of future asylum seekers, this looks very, very unwise. What might help them politically would be an asylum returns arrangement with the EU. But the Home Office refused to countenance remaining within the ready-made Dublin system at the time of Brexit, proposing a preposterously one-sided arrangement in its place. This was rejected out of hand by EU negotiators and the Home Office have shown no sign of shame-facedly trying to row back to it.

Literally no-one thinks Priti Patel is doing a good job. Her political career may in effect have already been ended by her tenure at the Home Office, as it has ended the career of many a previous Home Secretary since the turn of the millennium. All of them, except for Theresa May and Said Javid, in fact. Being offered the role of Home Secretary is the political equivalent of being handed the Black Spot.

Here on Free Movement

As long term readers will know, I like to make a record of how we’re doing on things we can actually measure, so that I can vaguely keep track of how we seem to be doing.

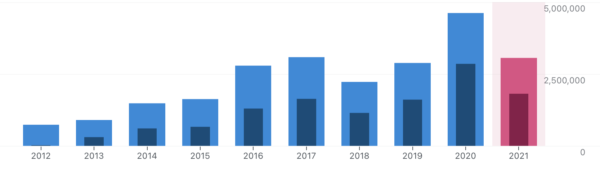

We received over 3 million page views from over 1.8 million visitors in 2021. That’s a lot of people looking for information, comment and analysis of immigration and asylum law, although less than in 2020. Just over 26k people subscribe to our emails now, up from 23k last year. On Twitter, my personal account now has 30k followers, up from 26k last year, and @freemovementlaw has 10k, up from 8k last year. We’ve now got over 3,300 active members, also up from last year, and several universities have purchased student access as well.

We published 427,254 words in 2021, broken down into 428 blog posts, making an average word count of 998 words per blog post. Our team of regular and occasional contributors has done sterling work this year.

CJ McKinney was promoted to Editor and has been joined by Rachel Westerby, who is managing the training content on the website. So far, Rachel has been carrying out an inventory and getting started on updating the existing content properly. Next year we’ll start adding to our range of courses again. Faye Clowes continues adroitly to manage customer queries and other vital administrative work.

On the home front, my children are now aged nine and eleven and I spend as much time with them as I can. I practice part-time from Garden Court Chambers, taking on mainly pro bono and legal aid work.

I finally published a co-written journal article on the hostile environment suite of policies with Melanie Griffiths at the beginning of the year. I’m still very proud of it, which isn’t always the case when I look back at things I’ve written.

A student textbook on refugee law for Bristol University Press I’ve been working on all year is now finished and due out in the spring. I learned a lot researching and writing it: there’s a lot more refugee law out there than I realised when I embarked on the project! I’ve also just handed in an updated version of Welcome to Britain for a paperback edition, also due out in the spring. As well as general Brexit-y updating I’ve added a short preface and new material on small boat crossings, economic migration policy and the Nationality and Borders Bill.

I’ll be doing a little bit of teaching at UWE early in 2022, I’m still working on an ongoing project to edit and write a high-level immigration law textbook with Bernard Ryan and I’d like to revamp the training offering at Free Movement to offer more personalised tuition to those who want it. We’ll be offering a range of materials and courses on the Nationality and Borders Bill once it is finalised.

I’m looking forward to 2022 and I hope you all are too.

SHARE

One Response