- BY Nick Nason

Father of three with sickle cell disease faces deportation for drug offences after six-year appeal saga

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Table of Contents

ToggleThe deportation case of a Nigerian man with sickle cell disease, resident in the UK for almost three decades, has been bouncing around the UK court system for over six years.

It appears the case has finally been settled by the Court of Appeal – on its second visit – in Secretary of State for the Home Department v PF (Nigeria) [2019] EWCA Civ 1139.

The case is unusual in dealing with arguments not often heard together: criminal deportation on the one hand, and Article 3 medical issues on the other.

“A long and tortuous history”

We don’t generally trouble readers with the full procedural backstory.

However, excluding the Supreme Court, the appellant in this case has now completed two full laps of the entire judicial system.

Setting the tone in 2013, the panel which first heard the appeal against the decision to deport – including a First-tier Tribunal judge and a non-legal lay member – apparently “disagreed on virtually all of the main issues, including issues of fact and assessment”.

The reason split decisions in the First-tier Tribunal are pretty unusual is because, as we learned from the first time this case was before the Court of Appeal ([2015] EWCA Civ 251), if the non-legal panel member disagrees with the judge, they are obligated to pretend otherwise and accept the decision (see paragraphs 25-27).

The panel’s failure to disguise their divisions – amongst other errors of law – meant that the appeal was remitted to a differently constituted tribunal where the appellant started again, mirroring the progress he made during his previous ascent: dismissal this time by the First-tier Tribunal, followed by success and clemency at the Upper Tribunal.

The Secretary of State appealed against the decision of the Upper Tribunal, and PF arrived back before the Court of Appeal, presumably now on first name terms with the bench.

The dread balance sheet

PF had been in the UK since 1990, arriving at the age of 13, with indefinite leave to remain since 2000. He had three British children, and was in a relationship with a British partner. All of the relationships were found to be genuine and subsisting ones.

The Court of Appeal accepted medical evidence that PF’s deportation would cause his children to be “apprehensive, perhaps even anxious or depressed”. In relation to the youngest daughter, “her development [was likely] to be significantly disturbed”.

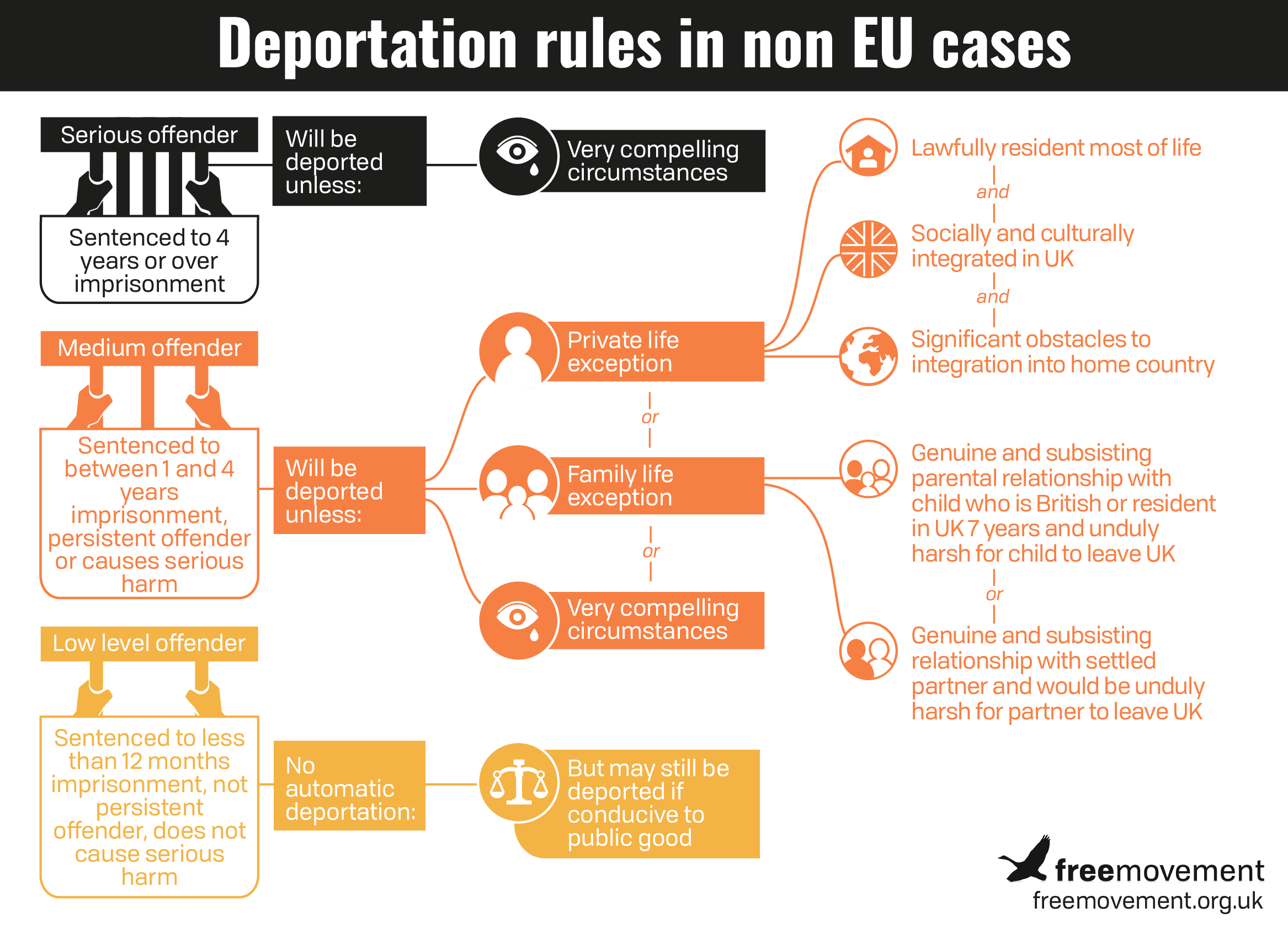

Against this stood the appellant’s rather imposing drug-related criminal history, including at least one section 117C(6) threshold sentence of over four years. This meant that the appellant was required to show “very compelling circumstances” as to why he should not be deported.

The unusual element of the case was that the appellant suffered from sickle cell disease. His legal team persuaded the Upper Tribunal not only that the new case of Paposhvili applied, but that his inevitable decline in Nigeria without treatment in the UK would be sufficient to meet this new test.

The Upper Tribunal was also persuaded that the 117C(6) “very compelling circumstances” test was met given the relationships with his children, and in combination with the medical findings, particularly that he would soon be dead (most likely within five years) if he were to be returned to Nigeria without medical treatment.

Pleading Paposhvili

Given the Court of Appeal’s recent stance on the applicability of Paposhvili v Belgium (application no. 41738/10), its decision to maintain that position was not surprising:

…the judge appears to have misunderstood the principle of stare decisis, as emphasised in AM (Zimbabwe) at [30] and MM (Malawi) at [9(i)], which requires all courts and tribunals to follow the House of Lords case of N unless and until it is overruled by the Supreme Court.

For completeness, the court found that, even if it were binding, the assessment of the Upper Tribunal that the appellant would be dead within five years of return was essentially wrong, and picked apart the evidence (given by three doctors) to that effect.

It is a matter of some concern that, in the course of doing so, the Court of Appeal accepted new evidence, including an article from an Nigerian online news site which was not before the Upper Tribunal, and a country of origin report about the availability of treatment which post-dated the hearing.

“Very compelling circumstances”

The Upper Tribunal had found that there were “very compelling circumstances” in PF‘s case which meant that he should succeed. These were

- the medical consequences of his deportation

- the impact of the relatively imminent death of their father for the children

The Upper Tribunal judge specifically stated that these were considered in combination:

… I find nothing except the medical issues outlined above in the discussion of article 3… can raise, in combination with other factors, a different and sufficient case for the [Respondent’s] deportation to also be disproportionate interference with his article 8 rights.

On this point (which the Upper Tribunal found took the case above the unduly harsh threshold), the Court of Appeal found that:

The fact that the children will, at some stage, have to face the death of their father abroad, again, falls far short of being unduly harsh, let alone a very compelling circumstance.

That the Court of Appeal had gone behind the views expressed by three doctors to find that the appellant would not necessarily die within five years assisted here.

Do as I say, not as I do

Having only the other week complained that the Upper Tribunal is too ready to find errors of law because it does not agree with a First-tier determination, or because it thinks it can produce a better one, the Court of Appeal has effectively done exactly this here.

It is surely open to a tribunal, having considered all of the evidence, to find that the fact that a child will have to face the prospect of their father’s painful death abroad, even if the exact period of time before death is unknown, is a very compelling circumstance, pushing it above the usual impact that deportation would have on a child.

The reasons given by the Court of Appeal (see paragraph 97) that it was not, appear simply to be disagreements with the conclusion reached. They significantly undermine the complaints made so vociferously by the same court in UT (Sri Lanka) v SSHD [2019] EWCA Civ 1095, citing with approval AH (Sudan) v SSHD [2007] UKHL 49: “Appellate courts should not rush to find such misdirections simply because they might have reached a different conclusion on the facts or expressed themselves differently“.

End of the road

Most problematic in this appeal is that, as one would normally see from the Court of Appeal, there was no remittal to the tribunal for a re-hearing. This was justified on the basis that ‘the evidence only admitted one outcome’ (paragraph 100), but presumably also because the Court of Appeal simply wanted to make it stop.

Given the history of the case, it is not likely the view that “the evidence only admitted one outcome” would necessarily be widely shared.

But it effectively means the end of the road for PF, with no onward rights of appeal save to the Supreme Court (which is presumably unlikely), and no opportunity to test the evidence advanced by the Secretary of State at the Court of Appeal, or to obtain further medical evidence, or to challenge the way in which the court arrived at its verdict on section 117C(6).

Obiter: “extra unduly harsh”

Lord Justice Hickinbottom poured cold water on Underhill LJ’s recent sass in SSHD v JG (Jamaica) [2019] EWCA Civ 982, in which the latter characterised the 117C(6) test as requiring appellants to show that the impact on their relevant child or partner would be “extra unduly harsh”.

The court agreed with the Home Office lawyer that the formulation

… risked masking a difference in approach required by section 117C(5) and (6) respectively: whilst KO held that the former requires an exclusive focus on the effects of deportation on the relevant child or partner, section 117C(6) requires those effects to be balanced against the section 117C(1) public interest in deporting foreign nationals. Under section 117C(6), the public interest is back in play.

In hindsight, this descent into the vernacular was perhaps an unhelpful addition to the canon.

SHARE