- BY Colin Yeo

A short history of refugees coming to Britain: from Huguenots to Ukrainians

It has become fashionable for government ministers to refer to “bespoke” humanitarian schemes and such like, referring to programmes like those for Ukrainians and Hong Kongers. The illusory scheme for Afghans was once trumpeted as a “bespoke” scheme as well, but it has effectively been mothballed and some of those who were evacuated back in 2021 are now on the verge of being made homeless.

What’s not to like about a “bespoke” scheme? It sounds fancy. And targeted. It evokes the idea of well-tailored suit from a high-end boutique. I have written before about my skepticism, though. Ministers are intentionally proposing withdrawal from the international legal framework that offers some limited rights to refugees and instead replacing that with an entirely discretionary system based on perceived national self-interest and a “pick-your-own” approach. I’ll return to that point at the end, in conclusion.

But first, some context. Let’s look back at the history of refugee arrivals in the UK. Right from the introduction of full immigration controls at the outset of the First World War, there has always been a mix of “bespoke” schemes for specific groups alongside unplanned arrivals. What follows is not a complete list and it is not based on thorough research (apart from the legal bits, which I’m confident are sound). It’s mainly drawn from a combination of Robert Winder’s excellent Bloody Foreigners, Jordanna Bailkin’s Unsettled: Refugee camps and the making of multi-cultural Britain and a bit of light Googling. I’d be interested to know where I’ve made mistakes or omissions, so get in touch if you spot anything glaring.

Before immigration controls

Prior to the passage of the Aliens Act 1905, there had been no permanent and official immigration controls in the United Kingdom. This meant that a person who wanted to come to the UK could do so, subject to paying for passage. There were no passports, no checks on arrival and no limitations on residence.

There are six groups I can think of who are known to have entered in significant numbers in this period.

Huguenots

Firstly, tens of thousands — estimates vary between 40,000 and 80,000 — of Protestant Huguenots fled to the United Kingdom from France over several decades following the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685. Those numbers sound small by today’s standards, but the population of the United Kingdom was far, far smaller so they had a significant impact at the time. Echoing refugee behaviour today, even more headed to other European countries, particularly Germany, the Netherlands and Switzerland.

Here in the UK, some seem to have integrated into communities and others established their own new communities, for example in the East End of London. They were distributed principally around the south of England. French churches were built, French road names followed and a Huguenot cemetery can still be found in Wandsworth. It has been estimated that Huguenots and their descendants made up 1% of the population by the time the migration petered out.

Poor Palatines

The Poor Palatines, as they were known, fared less well and were treated less generously. As Stephanie DeGooyer has explored, a debate raged in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries in the United Kingdom on the subject of naturalisation. The Naturalisation Act 1708 enabled far easier, large-scale and administrative naturalisation without the expense and inconvenience of a personal Act of Parliament. Shortly after its passage, an estimated 13,000 destitute Palatines from Germany unexpectedly arrived in the UK, fleeing the ravages of war. After being dispersed to Ireland and around the UK, many were eventually sent to America. The Naturalisation Act was quickly scrapped again and administrative naturalisation was only reintroduced in the late nineteen century.

French emigres

It is worth mentioning the French refugees of the revolutionary and Napoleonic eras. There was sympathy at an official level for those who had fled revolution but concern that revolutionary infiltrators might seek to stir up trouble. Successive governments were so concerned about national security that a series of Aliens Acts were passed between 1798 and 1815 restricting entry, regulating residence and requiring the use of passports. A whole new bureaucracy was brought into being along with legal checks and balances. A system of registration for aliens was retained after the war, which was gradually wound down and then fell into abeyance.

The Irish

It is thought around 1 million Irish died and 1.5 million emigrated during and after the Famine of the 1840s. It is unclear how many settled in the United Kingdom. Census figures probably understate the numbers, but to give an indication the official adult Irish population in the United Kingdom rose by over 300,000 from 289,000 in 1841 to over 600,000 by 1861.

There were no immigration controls and on top of that, this came after the Act of Union and so they entered as British subjects with the same right to enter and live in the United Kingdom as any other British subject.

They were not thought of as refugees then nor are they generally regarded as refugees now. Over the last 20 years or so, though, migration scholars have tried to reconceptualise what is sometimes called forced migration, sometimes survival migration. By todays standards, the Irish might be considered as refugees in the broad sense, although in common with some of the other groups they would probably not satisfy the modern legal definition of a refugee.

Political dissidents

There have been suggestions that the United Kingdom was a haven for political dissidents from Europe in the nineteenth century. The revolutions and uprisings of 1848 and ensuing repression generated many refugees, for example.

Not long after then, the foreign secretary, Lord Glanville, circulated a directive to all British missions stating that

‘[b]y the existing laws of Great Britain, all foreigners have the unrestricted right of entrance and residence in this country … No foreigner, as such, can be sent out of the country by the Executive Government, except persons removed by treaties with other States, confirmed by Act of Parliament, for the mutual surrender of criminal offenders.’

It is not clear what advice Glanville’s statement was based on and it is perhaps explicable by the exigencies of diplomacy and desire to reserve the right to offer asylum. But it offers some challenge to the idea of an unrestricted and continuing prerogative power to expel aliens.

I am unaware of any attempts to quantify how many people we might be talking about. I imagine the numbers were relatively small, but the individuals concerned were sometimes very prominent. Karl Marx springs to mind, for example. We can see popular concern about infiltration by anarchists and revolutionaries reflected in literature such as Joseph Conrad’s The Secret Agent in 1907, set a few decades earlier. The furore over ‘Peter the Painter’, a supposed anarchist supposed to be involved in the Sidney Street Siege of 1911, offers a real life expression of public anxiety.

Russian Jews

The final group of this era were the Jews who fled from Russia and Eastern Europe in response to pogroms, official hostility and expulsions. Between 1881 and 1914, around 150,000 are estimated to have arrived in the UK. There was nothing to stop them: there was no need to have permission to enter or live in the UK at that time. Eventually, though, following a prolonged anti-semitic campaign, the Aliens Act 1905 attempted to staunch the flow. Even then, though, only some migrants were subject to immigration controls at all, only on entry and there was an explicit exception for refugees:

…in the case of an immigrant who proves that he is seeking admission to this country solely to avoid prosecution or punishment on religious or political grounds or for an offence of a political character, or persecution, involving danger of imprisonment or danger to life or limb, on account of religious belief, leave to land shall not be refused on the ground merely of want of means, or the probability of his becoming a charge on the rates…

The legislation was passed at the end of a long period of Conservative Party political hegemony just before the Liberal landslide of 1906. The new Liberal Home Secretary, Herbert Gladstone, was faced with trying to implement the legislation. He rapidly wrote to the officials responsible for implementing and monitoring the legislation that a generous approach to the standard of proof should be adopted.

Quite different times.

Inter-war period

On the first day of the First World War, Parliament passed the Aliens Restriction Act 1914. It is a short piece of legislation — just two sections! — and by means of the Aliens Orders that it authorised the Home Secretary to make, it was to govern the entry, residence and regulation of aliens until 1 January 1973.

Belgians

Around a million Belgians left their country during the First World War, around one sixth of the total population. An estimated 250,000 sought refuge in the United Kingdom, the largest refugee movement in British history (excluding the post-Famine Irish). An estimated 35,000 arrived in Folkestone in just one month, between 20 September 1914 and 24 October 1914. They were accommodated in private homes, workhouses, asylums, hostels for vagrants and exhibition halls as well as refugee camps. Almost all then departed at the end of the war, some voluntarily and some rather less so.

This episode is probably the closest analogy we have to the Ukraine crisis, although there are important differences. It would not amount to refoulement (return into danger) to refuse entry to Ukrainians, unlike the Belgians, and it was therefore feasible (if morally questionable) to impose a visa requirement. What happens at the end of the conflict remains to be seen. The UK government’s official position at the moment is that all Ukrainian refugee will have to leave.

White Russians

Over 1 million Russians fled in the aftermath of the Bolshevik revolution of 1917. The exodus occurred over several years and the plight of Russian refugees led to the first tentative steps towards international refugee law. It has been suggested that the UK took in 15,000 so-called White Russians, from the army sponsored by the British and others to fight the Bolsheviks. But in reality there seems to be no evidence of their arrival and this assertion might be a mistake. Government policy was to refuse entry to all Russians unless there were exceptional circumstances. Only very small numbers seem to have been admitted, usually if they had business or strong personal connections and occasionally if they were high profile.

Basically, the British government did virtually nothing, leaving other European countries to host the refugees. Where refugees were evacuated by the British, it was to British territories, never to the United Kingdom itself.

Basque children

Following staunch Basque resistance in the north of Spain to Franco’s fascist forces, the Home Office agreed in 1937 to accept 2,000 Basque children as refugees, later increased to 4,000, under pressure of public sympathy following Guernica. They were accommodated in tents in fields near Southampton, rented from a local farmer. Most then seem to have been able to return to their parents in Spain.

German Jews

In 1938, in the aftermath of Kristallnacht, the British government, under pressure from Jewish refugee agencies, agreed to accept 5,000 unaccompanied refugee children under the age of 17 from Germany, Austria and Czechoslovakia. This increased to 10,000 after the Colonial Office refused to allow a further 10,000 children to enter Palestine. The children were evacuated by train then ferry from the Netherlands over a period of nine months, ending with the outbreak of war. The Kindertransporte were daily in June and July 1939. Those with contacts were accommodated in private homes and others were temporarily placed in summer holiday camps in East Anglia.

Their parents were left behind, a point that those rehearsing the trope about past British generosity to refugees seem to forget.

But some Jewish adult refugees were also permitted to enter. Around 4,000 men between the ages of 18 and 40 were sponsored for transit visas by the Central British Fund for German Jewry. They were supposed to re-emigrate elsewhere. In the final months leading up to the outbreak of war further Jews fled from Belgium, Italy and Czechoslovakia and were accommodated in camps on arrival. Ultimately, it has been estimated that around 80,000 Jews found refuge in the UK, mostly on a temporary basis en route elsewhere.

Post-war period

The Refugee Convention was agreed in 1951 and came into force in 1954. Prior to the agreement of a Protocol in 1967, it only applied to those who had fled because of events prior to 1 January 1951. It was intended as a sort of mopping-up exercise for those refugees who remained in Europe following the repatriation and resettlement schemes of the late 1940s.

Post-war Poles

Around 200,000 Poles found refuge in the United Kingdom after the war by a variety of means. Some had served in the British military (over 20,000 died under British command during the war), some fled from the Nazis, some were Nazi collaborators, some were POWs liberated in the final stages of the war and some had fled from Soviet control. A further 33,000 Polish dependents entered the UK between 1945 and 1950.

Immediately after the war, the British government had hoped Poles would be able to return home. The Soviet take-over of Poland combined with the general shift from repatriation to resettlement of wartime refugees led to a change of approach. In October 1946, 120,000 Polish troops were accommodated in camps. The Polish Resettlement Act 1947 legislated for provision of camp accommodation and access to welfare benefits. By 1948, the number remaining in camps had dropped to 16,500.

European Volunteer Worker Scheme

Under the auspices of the European Volunteer Worker scheme, the United Kingdom recruited an estimated 91,000 displaced people from the Baltics, Balkans and central and eastern Europe as workers in the post-war years under circumstances that in truth involved a significant degree of compulsion.

Refugees could return to their own countries voluntarily should they wish to, and the fact the workers were refugees and therefore could not be forced to leave if they fell sick or were judged unsuitable was considered by British officials a disadvantage.

Hungarians

Around 200,000 Hungarians fled their country after the Soviet invasion of October 1956. The initial Home Office response was to hand pick a select few Hungarians from Austrian refugee camps but immigration restrictions were temporarily lifted for Hungarians in November 1956. The plan was to accept around 2,500 Hungarian refugees, but in the end nearly 22,000 were admitted. As many as 11,000 passed through camps in southern and south-eastern England.

Anglo-Egyptians

One consequence of British complicity in the Suez Crisis of 1956 — the British, French and Israeli governments together invaded Egypt to attempt to oust President Nasser and regain control of the Suez canal — was the expulsion from Egypt of all British subjects. Known as the Anglo-Egyptians or ‘Nasser refugees’, around half of the seven or eight thousand who subsequently arrived in the UK were Maltese. Most did not speak English and few had been to Britain before. They too were accommodated in camps, which were in short supply because of the simultaneous Hungarian crisis.

I am not clear on whether there was an evacuation or whether those concerned travelled under their own steam, so to speak. They were British subjects, though. Because this was before the Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1962, they were therefore free to enter.

Cold War

There was a constant trickle of political refugees, sometimes labelled as dissidents or defectors, during the Cold War. I haven’t yet tried to quantify this and would be interested to see any estimates. They are possibly the smallest group of refugees of all, yet loom the largest in the official and public imagination.

Political dissidents from an ‘evil’ regime are now considered to be the paradigm refugee; they are thought of as ‘proper’ refugees, unlike many others. The idea that post-Cold War refugees were the intended beneficiaries of the Refugee Convention and those who came later, from the 1990s onwards, are somehow different has been described by Indian scholar B.S. Chimney as the ‘myth of difference’. In reality, dedicated political dissidents have always been few and far between. As this short history I think shows, ‘refugees’ have always been understood as much wider class. And many of those who slipped through the Iron Curtain were simply seeking a better, free-er life rather than fleeing personal and targeted persecution.

East African Asians

From the early 1960s to the mid 1970s, it is thought around 150,000 to 200,000 East African Asians, as they were known, relocated from mainly Kenya and Uganda to the United Kingdom. Their ancestors had relocated from British India in previous centuries and decades but their position in the newly independent countries seemed precarious, with some politicians indulging in hostile rhetoric.

The oddities of the Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1962 meant that they lost the right to enter and reside the UK in 1962 but then regained it in the following years as their countries became independent. Many from Kenya did so, followed by increasing numbers from Uganda, and this generated racist political anxiety in the UK. The Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1968 followed, preventing others from following.

When Idi Amin seized power in Uganda, the rhetoric increased and then in 1972 he announced he was expelling all holders of United Kingdom and Colonies passports. This was Enoch Powell’s heyday and after trying and failing to find other countries willing to accept the Ugandans, Ted Heath’s Conservative Government assisted in their evacuation. The government sought other solutions first but, to their credit, did eventually accept around 21,000 Ugandans, who passed through refugee camps in the United Kingdom.

I’ve seen no suggestion that the East African Asians, even those evacuated from Uganda, were regarded as or referred to as refugees at the time. They perhaps illustrate the absurdities of trying to draw a sharp distinction between economic migrants and refugees. Some would have met the legal definition of a refugee; they were almost all also economic migrants seeking a decent life for themselves and their children.

Chileans

The right-wing military coup in Chile led by Augusto Pinochet in 1973 led to severe political persecution. I was aware from a conversation years ago with Mick Chatwin, one of the early immigration and asylum lawyers, that Chilean refugees had sought sanctuary in the UK. It turns out some sort of scheme was instituted under which 14,000 Latin Americans were considered by the Home Office between 1973 and 1973. Around 4,000 were resettled here and were mainly Chilean.

Vietnamese

The Vietcong victory in 1975 triggered a huge refugee crisis spread over several years. Over 130,000 entered the United States within a fortnight. Only 32 were initially admitted to the United Kingdom.

Referred to as ‘boat people’, more than 250,000 lost their lives at sea. In 1978 and 1979, two British ships rescued groups of several hundred refugees in distress who were then relocated to the United Kingdom. By 1979, over 60,000 had reached Hong Kong, then a British colony, and were accommodated in camps. The UN negotiated and co-ordinated resettlement but the UK initially proposed to resettle 1,500 Vietnamese refugees. Under pressure, Thatcher’s government reluctantly agreed to accept another 10,000.

Between 1978 and 1982, successive British governments admitted around 22,500 Vietnamese refugees.

Sri Lankan Tamils

The outbreak of the Sri Lankan civil war in the 1980s, accompanied by racist violence against the Tamil community, led many to flee and claim asylum abroad. The United Kingdom was one obvious destination given the historic links and shared language; Sri Lanka was a British colony until 1948 and Sri Lankans had continued to be British subjects until 1 January 1983. The Sri Lankan Tamils were the first of a new asylum trend in which victims of violence and human rights abuses — and sometimes others as well — travelled long distances themselves in order to claim asylum in the Global North (which includes Australia, for those unfamiliar with the term). But I’ve singled them out for a reason.

In common with all other Commonwealth citizens, Sri Lankans did not require a visa to travel to the United Kingdom for temporary purposes. This meant that they could board a flight to the UK and if they were refused entry, for example as a student or visitor, they could then claim asylum. A visa requirement was imposed in 1985 in response to hundreds of Tamils arriving per day.

This proved insufficient, because airlines sometimes allowed passengers to board who did not possess a visa. Once the passenger had reached the UK, they could claim asylum. So, the government legislated to impose penalties for carrying passengers without visas. This was very explicitly linked to asylum claims by then-Home Secretary Douglas Hurd as he opened the Second Reading for the Immigration (Carriers’ Liability) Bill 1987:

The immediate spur to this proposal has been the arrival of over 800 people claiming asylum in the three months up to the end of February.

The majority of those claiming asylum had been Tamils. Rather unconvincingly, Hurd immediately ploughed on:

So this is not a Bill about Tamils alone, or about Sri Lanka alone. It goes wider than that. Its aim is to make sure that our immigration control remains effective in the face of rapidly changing international pressures. We have to reconcile that aim with our international obligation to help the genuine victims of persecution.

The legendary Alf Dubs, then a Labour MP but later a Lord, tabled an amendment to exempt carriers should the passenger transpire to be a refugee. It was unsuccessful.

Balkan refugees

The descent of the former Yugoslavia into vicious civil war in the early 1990s caused a major refugee crisis right at the edge of Europe. Around 1.3 million people fled abroad. Germany received around 320,000 Bosnian refugees. Around 75% Of them were reportedly repatriated at the end of the conflict. A group of around 4,000 Bosnians were resettled to the UK in 1993 and a further 500 in 1995. Meanwhile, around 14,000 arrived independently.

Very few were properly recognised as refugees, despite the fact that the vast majority must have fulfilled the legal definition of a refugee. Many seem to have returned home at the end of the conflict, although how willingly is not clear.

The crisis in Kosovo in the late 1990s generated a new wave of refugees. Around 4,300 were evacuated directly to the UK in 1999, some others followed through family reunion, and several thousand arrived independently to claim asylum. Until late 1999, temporary leave was granted on application, after which individual consideration resumed. When the war ended at least some were repatriated but I have not been able easily to find numbers for this.

Irregular arrivals

Since the Tamils started to arrive and claim asylum in the 1980s, we have seen various nationalities rise to prominence in the asylum statistics. Turkish Kurds, Somalis, Iraqis, Afghans, Syrians and others have come. The rise and fall in asylum claims for different nationalities typically reflects the levels of repression and violence in their countries of origin, giving lie to the idea that most are ‘merely’ economic migrants.

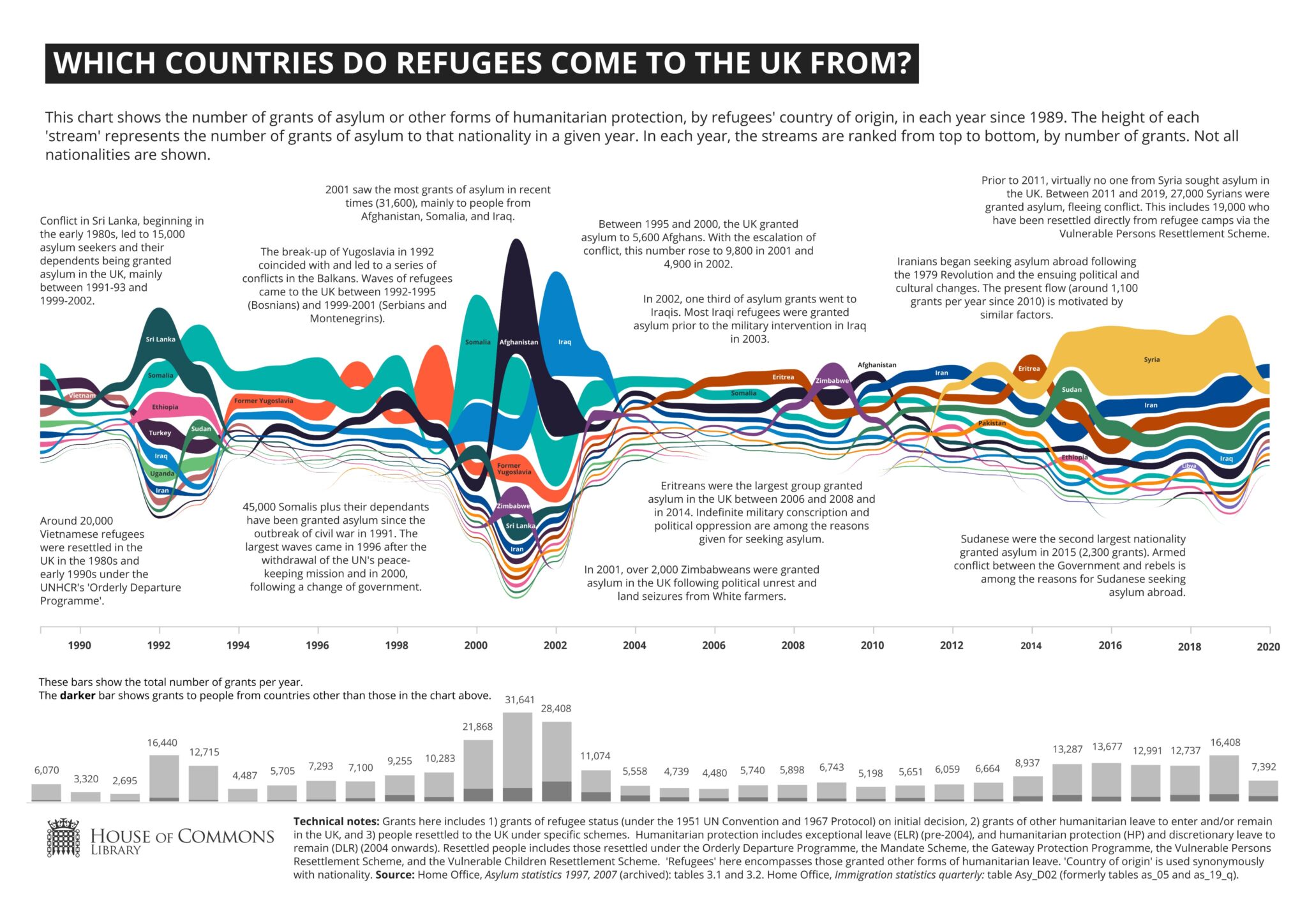

This brilliant chart by the even more brilliant Georgina Sturge from the House of Commons library team illustrates grants of asylum by nationality between the late 1980s and the present day:

Hong Kong

A uncapped scheme to enable Hong Kong residents with British nationality to relocate to the United Kingdom was launched in 2020. This came in response to increasing repression in Hong Kong and interference by the central Chinese government with the hitherto quasi-independent government of the island. It is not a refugee programme and does not involve anything as dramatic as an evacuation. It is a visa programme, and a fairly expensive one at that. Applications cost. So far, around 140,000 Hong Kong residents have relocated under the scheme. Entrants will be eligible for settlement on payment of a further hefty fee after five years of residence.

Ukrainian

The United Kingdom government set up a free and uncapped visa scheme for Ukrainians following the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. Unlike all other European countries, the UK decided to require Ukrainians to apply for a visa before being admitted. This meant that the millions who fled into Poland and Moldova could not simply come to the UK, unlike to other countries. There were huge administrative problems with the scheme at the outset and the knock-on effects of devoting so many Home Office resources to the scheme — a scheme which many thought unnecessary in the first place — continue to be felt with long waiting times for other types of visa application. The most recent statistics show that 175,800 Ukrainians have entered the UK on this visa scheme. Some of them will already have returned home.

It is unknown what will happen to the Ukrainians in the UK and indeed in other countries if or when the war finally ends, or at least cools. The official government position is that Ukrainian visas are for a period of three years and cannot be renewed. It seems likely, or at least possible, that some sort of transition to more permanent status will be possible for at least some Ukrainians, who will have established new lives for themselves in the meantime. But at the time of writing, that remains to be seen. In the past, refugees have been strongly encouraged to return home.

Conclusion

The United Kingdom does have a long history of receiving refugees. Whether it is a proud record of welcoming refugees is more questionable. Until 2020, successive government were often reluctant to receive refugees and the public was often more sympathetic. New controls were imposed and invented to prevent refugee arrivals. Governments sometimes expanded schemes after their initial caution but resettlement programmes were generally limited to a few thousand refugees per year. The Hong Kong and Ukraine schemes represent a major change in approach.

There is an argument that ‘bespoke’ schemes for targeted groups of refugees are in fact the norm since the imposition of immigration controls on aliens during the the First World War, at least in the period up to the 1980s. Many but not all passed through camps, community sponsorship, as it is now known, was frequently deployed and on other occasions refugees were just expected to find jobs and get on with it themselves.

The problem with ‘bespoke’ schemes, though, is that it becomes likely that discrimination occurs. We’ll refuse to take young men with dark skins from the Middle East or Africa, for example. But we will take women and children with white skins from Ukraine and wealthy, skilled Hong Kongers.

This can raise sharp political division. Discrimination has two potential meanings, after all. Today and in legal circles, we generally consider discrimination to be bad; we mean unlawful discrimination on the basis of a protected characteristic. The word can also be understood to mean exercising refined choice or taste, in a positive sense. Some will consider selection of refugees to be a common sense and obviously positive proposition. Others will consider it to be socially harmful and unfair.

There is also the question of what happens to the refugees who get left behind because nobody wants them. When states acted in this way in the past, Jews were turned away because of antisemitism. After the second world war, tens of thousands of ill, disabled and elderly refugees were left for many years in refugee camps across Western Europe; all of the bespoke schemes run by various governments required refugees to be fit and able to work. The others were abandoned and ignored. Have a read of Robert Kee’s Refugee World from 1961, which is, bizarrely, available on Kindle Unlimited. He visited the camps and spoke to the refugees themselves and those working for the charities and governmental bodies attempting to resettle them.

This is not to say that bespoke schemes are bad. They obviously are not. But they should sit alongside the Refugee Convention, not replace it. Refugees should be — and are, according to international refugee law — permitted some agency about where they seek refuge.

Want to really get to grips with refugee law? Concise and readable, Colin’s textbook walks you through everything from well-founded fear to refoulement.

SHARE

One Response