- BY Sonia Lenegan

LGBT+ people face persecution and are no less deserving of protection

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

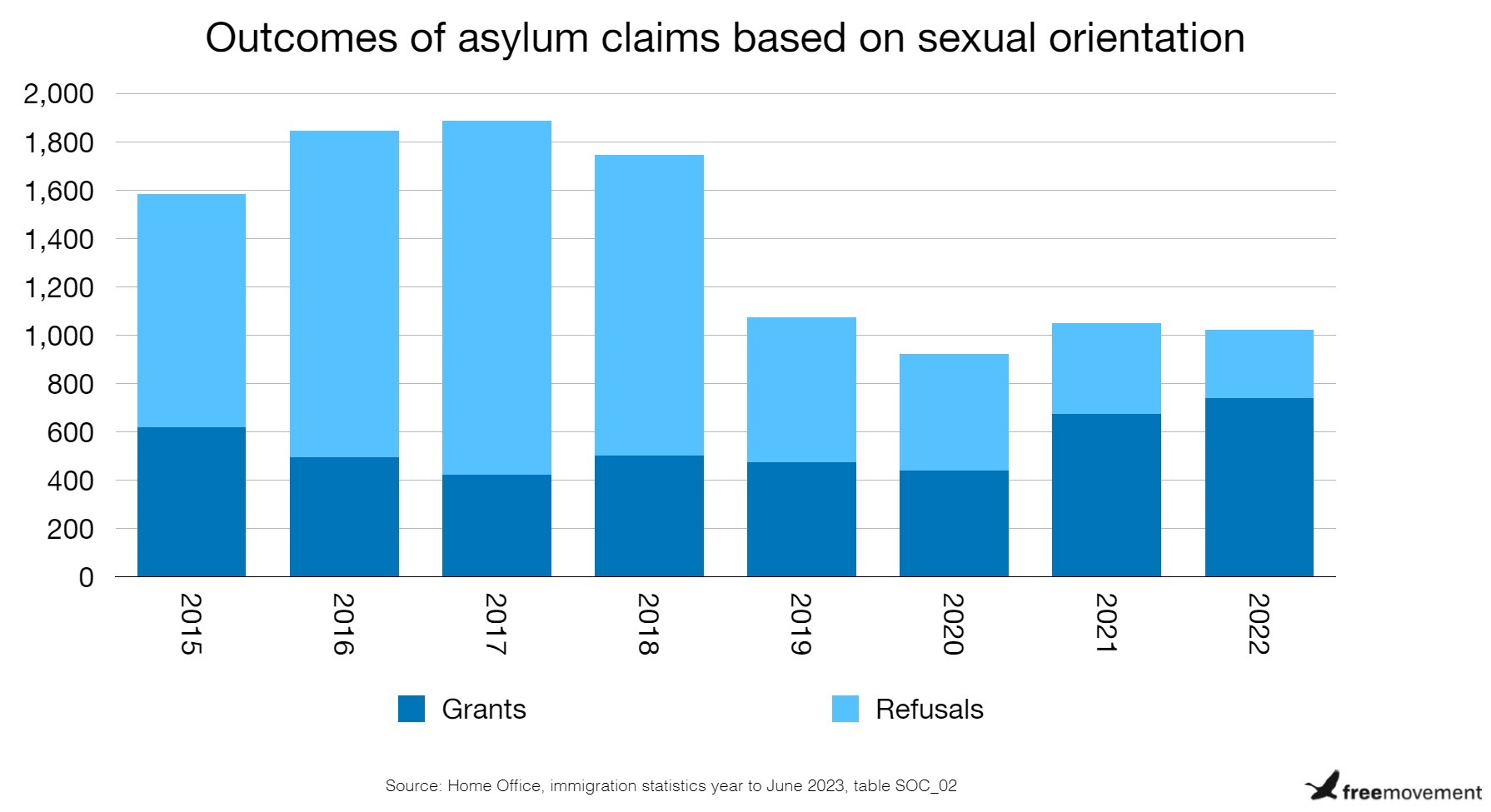

Last year 1,334 people came to the UK and claimed asylum based on their sexual orientation, amounting to 2% of all asylum claims. A lot of them are probably feeling quite frightened this morning after the Home Secretary has chosen to single them out for attack, as being undeserving of safety.

There are 66 countries in which same-sex sexual activity is illegal. In a large proportion of these countries, the laws are a legacy of British colonialism. The Prime Minister in 2018 said that:

I am all too aware that these laws were often put in place by my own country. They were wrong then, and they are wrong now. As the UK’s Prime Minister, I deeply regret both the fact that such laws were introduced, and the legacy of discrimination, violence and even death that persists today.

Only this year, the Ugandan government passed a new law that provides for a 20 year prison sentence for the “promotion of homosexuality” which could include organisations advocating for the rights of LGBT+ people. This law also provides for life imprisonment and even the death penalty to be given in some cases of same sex activity. The police carry out raids on gay bars and LGBT+ shelters and those arrested face “being humiliated, harassed, sexually assaulted, threatened with rape and subjected to forced anal examination”.

In Afghanistan, a Taliban judge said that gay men should be executed by being stoned to death or having a wall toppled onto them. In October 2022 a gay student was tortured for three days before being murdered. In October 2021 the government announced that they had evacuated 29 LGBT+ people from Afghanistan, saying that “LGBT people are among the most vulnerable in Afghanistan, with many facing increased levels of persecution, discrimination, and assault”.

In Nigeria, the police “sometimes subject LGBTI people to harassment, beatings and assault, sexual violence and rape, torture, blackmail and extortion”. Pakistan criminalises same sex activity between men. In Iran, the penalties for same sex activity for gay men “range from flogging to the death penalty”. I could go on.

Mistreatment of LGBT+ people in these and many other countries goes far beyond discrimination and the government has rightly acknowledged this by recognising those in need as refugees.

Since 2015 the government has published statistics on people who have come to the UK and claimed asylum based on their sexual orientation. They do not do the same for claims based on gender identity and they do not provide a gender breakdown of the sexual orientation claims.

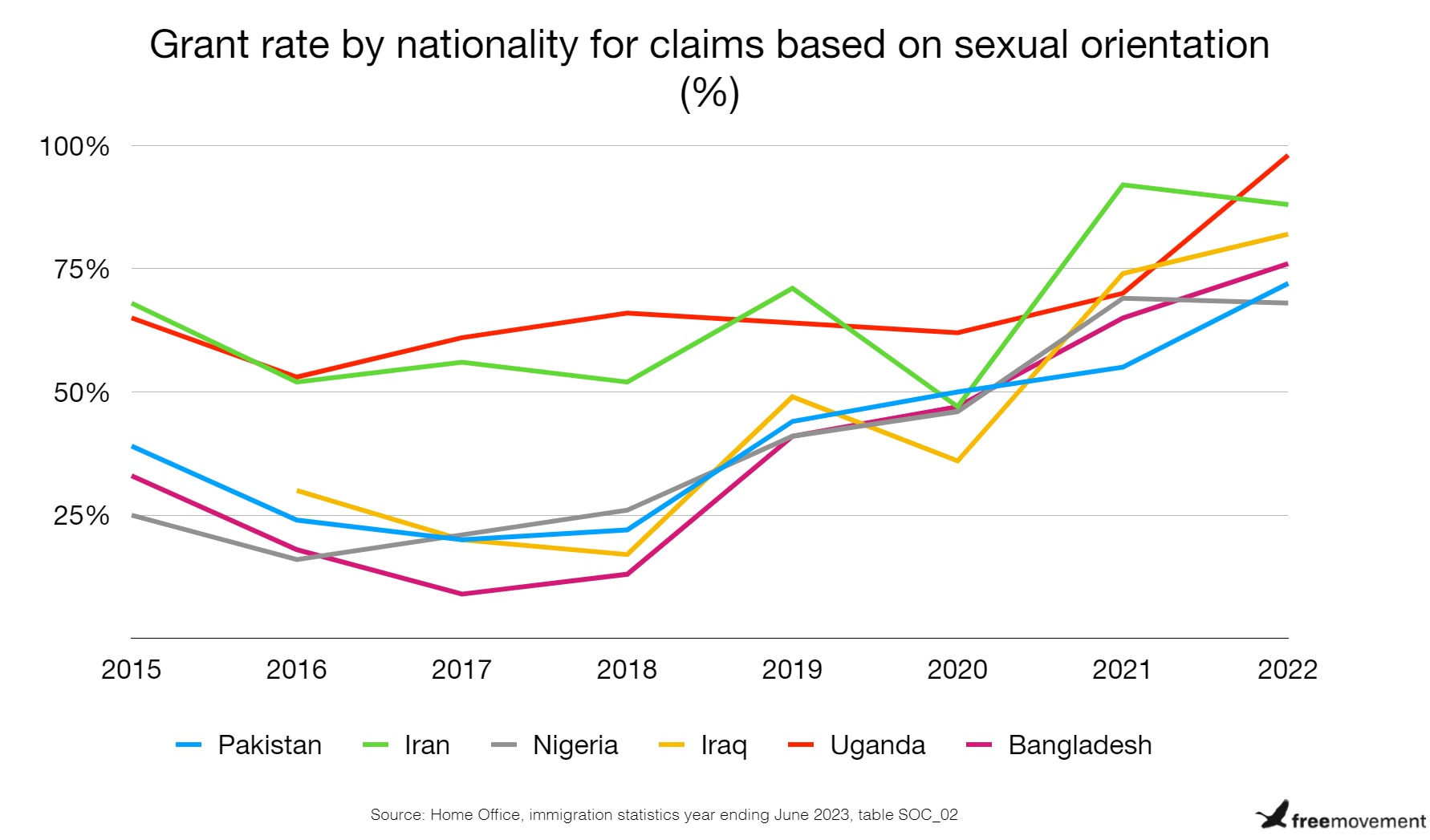

The top grant rate countries are unsurprisingly Uganda and Iran, with Uganda’s grant rate in 2022 being 98%.

Historically, these claims had a very low success rate. The Home Office’s culture of disbelief towards LGBT+ people was and remains a problem, as ably demonstrated by former immigration minister Chris Philp MP this morning. However some progress has been made. The overall grant rate was 39% in 2015 and was 72% in 2022 which is almost identical to the figure for all asylum claims.

Being LGBT+ can make seeking safety more difficult, as it is not unusual for neighbouring countries to also have hostile attitudes towards them. Safe and legal routes such as we have seen for Ukraine, Syria, Afghanistan simply do not exist for people who face persecution because of their sexual orientation or gender identity. This is a group of people who are already disadvantaged within the asylum and resettlement system.

Conclusion

Government asylum policy rarely takes into consideration the specific and different needs of LGBT+ people seeking asylum. Examples include the Rwanda agreement and the disproportionate number of problems in asylum accommodation experienced by LGBT+ people. The Home Secretary may say that anyone suffering persecution still deserves protection but the overall message is clear: this does not include LGBT+ people. Targetting such a small and vulnerable group on an international stage is a new, yet unsurprising, low.

SHARE

2 responses