- BY John Vassiliou

Yemen-born Somalis in High Court fight for British Overseas Citizenship

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Table of Contents

ToggleDespite our remarks in previous blogs about the useless nature of British Overseas Citizen status, a series of judgments handed down by the High Court this summer demonstrate that this unusual version of British nationality is sufficiently valuable to encourage the pursuit of lengthy and expensive litigation against BOC passport refusals. All of the cases were heard by Mrs Justice Lang and concern people of Somali heritage born in Yemen before it gained independence. All are fact-specific, but immigration practitioners may be interested in the entitlement of this group to BOC status in the first place, the expert evidence on Somali culture and the form the litigation took.

Brief geopolitical history notes

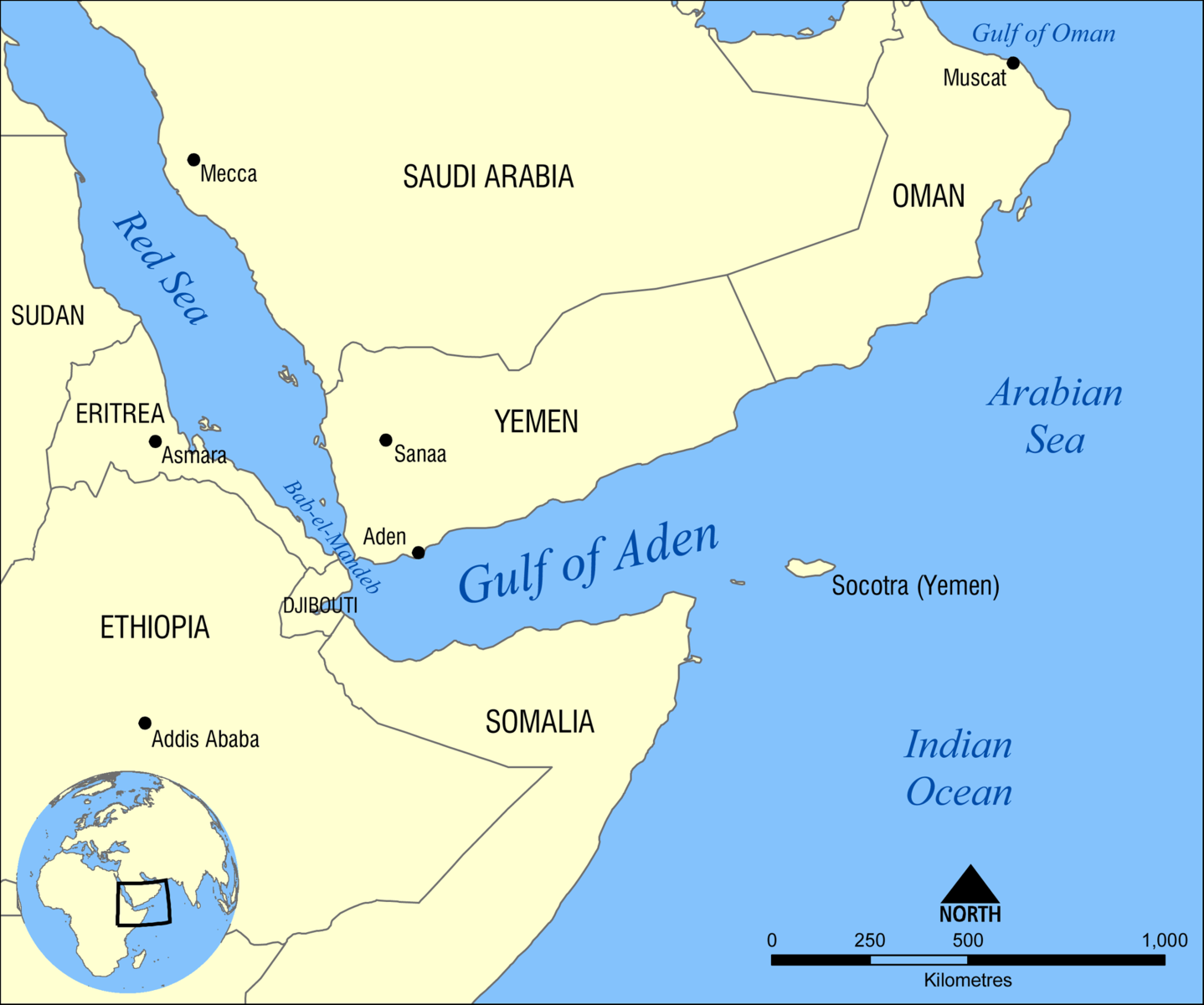

Aden is a historic port city in what is now Yemen, in the Middle East. The city sits on the coast of the Gulf of Aden on the approach to the Red Sea. Its harbour is the crater of a dormant volcano.

Between 1839 and 1967 Aden was ruled by the British Empire. It had the status of a Crown Colony until 1963, when it became the “State of Aden within the British Protected Federation of South Arabia”. In November 1967 the city-state gained independence from the British Empire as the capital of the newly established People’s Republic of South Yemen.

Due south, across the Gulf of Aden, lie the northern banks of Somalia. A large number of people of Somali heritage have historically lived in Aden. Under Southern Yemeni nationality law provisions introduced in August 1968, citizenship of the new country was conferred only on those considered to be “Arabs” born in Southern Yemen of whom one or both parents had resided in Southern Yemen for at least five years. Somalis were not considered to be “Arabs” for the purposes of Southern Yemeni nationality law.

[ebook 57266]Consequently, Somalis who had been born in Aden as British Subjects or (after 1 January 1949) Citizens of the United Kingdom and Colonies, retained their CUKC status: R (Botan) v Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs CO/1484/200.

Aden-born Somalis retained their CUKC status until commencement of the British Nationality Act 1981 on 1 January 1983, at which time they became another ugly acronym: BOCs, or British Overseas Citizens. BOCs, unlike British citizens, do not have the right of abode in the UK and consequently the status does not offer very much to its holder.

The upshot of all of this is that many Somalis living in Yemen may still have an entitlement to BOC status if they want it.

Challenging a British Overseas Citizen passport refusal

Someone claiming to be a British Overseas Citizen may apply directly to the Passport Office for a BOC passport. If the passport application is refused, the only remedy is judicial review, though not in the traditional sense. The Secretary of State has no discretion when it comes to issuing a passport to someone who is a BOC: either a person is entitled to one or they are not. The question of whether or not a person is a BOC is therefore a question of precedent fact, to be determined by the court based on the evidence before it: R (Harrison) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2003] EWCA Civ 432. Unlike a “traditional” judicial review

the court does not consider whether, applying public law principles, the Defendant was entitled to find that the Claimant had not proved that they were the holders of their claimed identity, but instead considers for itself whether the Claimant has established the claimed identity.

The burden of proof lies with the claimant, and the standard of proof is the balance of probabilities: R (Bondada) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2015] EWHC 2661 (Admin). Tim Buley briefly discusses precedent fact judicial reviews in the context of Windrush cases in this post.

One of the main barriers to Somalis from Aden proving their entitlement to BOC status is the difficulty of providing satisfactory documentary evidence of their birth and their identity. It can be very hard to produce contemporaneous original evidence from several decades ago, particularly from a country like Yemen.

In all of the High Court cases, the Passport Office refused to accept the claims of entitlement to BOC status. The consequence? A six-day hearing of the lead case of R (Nooh) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2018] EWHC 1572 (Admin), during which a significant amount of expert evidence on Somali culture had to be led. The other two cases of R (Taher) v SSHD [2018] EWHC 2274 (Admin) and R (Suleiman) v SSHD [2018] EWHC 2273 (Admin) were heard over the course of one day each.

Dates of birth and naming conventions in Somali culture

In Somali culture, dates of birth have little significance. The court heard evidence from Dr Markus Hoehne, an anthropologist at the University of Leipzig whose report confirmed that dates of birth are not usually registered and birthdays play no role in Somali culture. Before the colonial period there was no registry of births and even now most Somalis are born without official birth registration. Dates of birth would more likely be attached to significant events around the time of their birth. Since the 1980s there is an awareness of a year of birth generally but not necessarily of the exact date which would often simply be guessed.

Dr Hoehne also gave evidence on Somali naming conventions which on a broader level will be useful for any practitioners dealing with Somali nationals in any immigration context

Dr Hoehne explained that there are no family names in Somali culture. Names are constructed in the following order: a person’s first name, father’s first name, grandfather’s first name. [Suleiman, para 35]

When European authorities register Somali names, they tend to adopt the last name as the family name or surname of the person, in an attempt to adjust them to a European taxonomy of naming. In this case, the Claimant’s grandfather’s first name – Suleiman – has been treated as if it was her surname. As Dr Hoehne explained, from a Somali perspective, this does not make sense, and gives rise to confusion. [Suleiman, para 36]

A further evidential difficulty with Somali names is the proliferation of inconsistent name spellings and indeed inconsistent names. Dr Hoehne explained that many Somalis use family nicknames, with many parents often calling their children by different names than their official recorded names. This can give rise to confusion and ambiguity when trying to match up official documents with oral testimony.

With regards to the spelling of names, Dr Martin Orwin from the School of Oriental and African Studies gave evidence that

The Latin alphabet was introduced as the official writing system for Somali in 1972; prior to that different writing systems were used. He explained that the Somali language has no standard form. It comprises a set of dialects, and there are variations in the ways in which words are spoken and written. In addition, grammatical and spelling errors are commonplace in written Somali. [Suleiman, para 31] [T]he problem of inconsistent spelling is exacerbated when Somali or Arabic names are spelt in an English-speaking context, because of the representation, or lack of representation, of sounds found in Somali and/or Arabic, but not in English. Dr Orwin gave the example of the spelling of the Arabic name Muhammad which is spelt in a number of different ways in English e.g. Muhamad, Muhammad, Mohamad, Mohammad, Mohamed, Mohammed, Mahamad, Mahamed etc. He explained that these are not different names, but simply different anglicised spellings of the same name. [Suleiman, para 32]

Outcome of the litigation

In all but the Taher case, the claimants obtained the declaration they sought. In Taher, the claimant was found not to be a credible witness and his oral evidence was unreliable where unsupported by documentary evidence.

Why did they go through all of this litigation if BOC status does not confer the right of abode? I can only speculate: perhaps travel around the world is easier on a BOC passport than a Somali passport, and perhaps British consular support is more effective its Somali equivalent. Of course those involved will have wanted a document that rightfully ought to have been theirs. But litigation is lengthy, costly and stressful, and usually there is some more practical advantage than abstract justice to be gained from its pursuit. If anyone can tell me what that practical advantage was, do leave a comment below.

SHARE