- BY Josie Laidman

What is going on with small boat crossings and the new refugee camps?

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Table of Contents

ToggleThe Home Affairs Select Committee held an oral evidence session about Channel crossings and other key asylum issues last week. Since the evidence that was heard on Wednesday, figures and quotes have hit the headlines. Criticism of Suella Braverman has been extensive and the Manston processing centre has become the focus of several articles.

A lot of what has happened over the last few days goes back to the evidence that was given at the Home Affairs Select Committee session last week, so we thought it would be useful to recap what was said. Despite the current headlines, it is still unclear whether there any signs of future improvement in both the asylum decision-making backlog and the interim process and protocol.

The figures

So far in 2022, 38,000 people have arrived in the UK on 936 boats. There was a particularly large increase in numbers in August and September. And France has already stopped 28,000 people and intercepted and destroyed 1,072 boats so far this year. This is approximately double the number of boats stopped compared to 2021.

Dan O’Mahoney, the director of the clandestine channel threat command, is responsible for the government’s operational response to small boats. He stated, without any real evidence, that “[t]he big phenomenon this year is that it has changed from almost exclusively an asylum problem to 50:50 an asylum problem and an illegal migration problem”. In terms of who is arriving, O’Mahoney said that:

“[I]t might be helpful to paint a picture of the type of illegal migration that we are talking about this year, and just how quickly the scale has accelerated. Two years ago, 50 Albanians arrived in the UK in small boats. Last year, it was 800. This year, so far, it has been 12,000 – of which about 10,000 are single, adult men. The rise has been exponential, and we think that is in the main due to the fact that Albanian criminal gangs have gained a foothold in the north of France and have begun facilitating very large numbers of migrants.

Within this cohort, there are undoubtedly people who need our help, but there is also a large number who are deliberately gaming the system.”

The grant rate for single Albanian men is apparently only around 12%. But this does not factor in the delays in granting asylum, in comparison to any changes in country information or danger to individuals. We have explored experiences of the types of Albanian asylum or trafficking claims here, but there are concerning sections of the evidence that may be simplifying a number of reasons individuals from Albania are currently entering the UK:

“Albania is a member of the signatory to the Council of Europe convention on action against trafficking in human beings. Just as British victims in the UK access our system, the government are seeking to avoid Albanian nationals using people smugglers to get to the UK to seek protection under the [national referral mechanism]. That is available to them in Albania.”

Country policy guidance confirms that trafficking is still a significant problem in Albania and the country does not yet meet some of the minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking. However, Robert Jenrick, the new Minister of State (Minister for Immigration), claimed in the House of Commons yesterday that “Albania is quite clearly a safe country and those individuals have crossed through multiple other safe countries” before arriving in the UK. Jenrick told the House of Commons that government officials wanted to work with Albanian authorities in the hope of reaching an agreement on immigration and that they were “considering whether there is a bespoke route for Albanians to have their cases heard quickly and [be] removed from the country if they are not found to be successful [and] returned to Albania”.

Yet in 2021 98% of those crossing on boats claimed asylum. So far this year, 93% have. In 2021, of those asylum claims that have been completed, 85% were granted. This is a particularly high number, and arguably justifies a significant change in attitude and support for those crossing the Channel in small boats moving forward.

The backlog

Whilst the attitude towards asylum seekers entering the UK is troubling, the rate of decision-making for these asylum seekers and the consequences delays have on their lives is also no small issue. It is worrying that 95% of the claims from 2021 have not been completed and individuals are still awaiting decisions. Only 4% of those who arrived by boat in 2021 have had a decision on their claim. The backlog of asylum cases is only increasing.

Home Office statistics paint a picture of how decision-making has exponentially slowed. Of applications submitted in the last quarter of 2021, only 7% received a decision within 6 months. In 2018, 56% received a decision within 6 months, and that number was over 80% in 2015. All this leaves individuals relying on Home Office accommodation for longer and longer periods, meaning that the department can’t reduce their use of hotels or other temporary accommodation sites, further driving up the cost of the system.

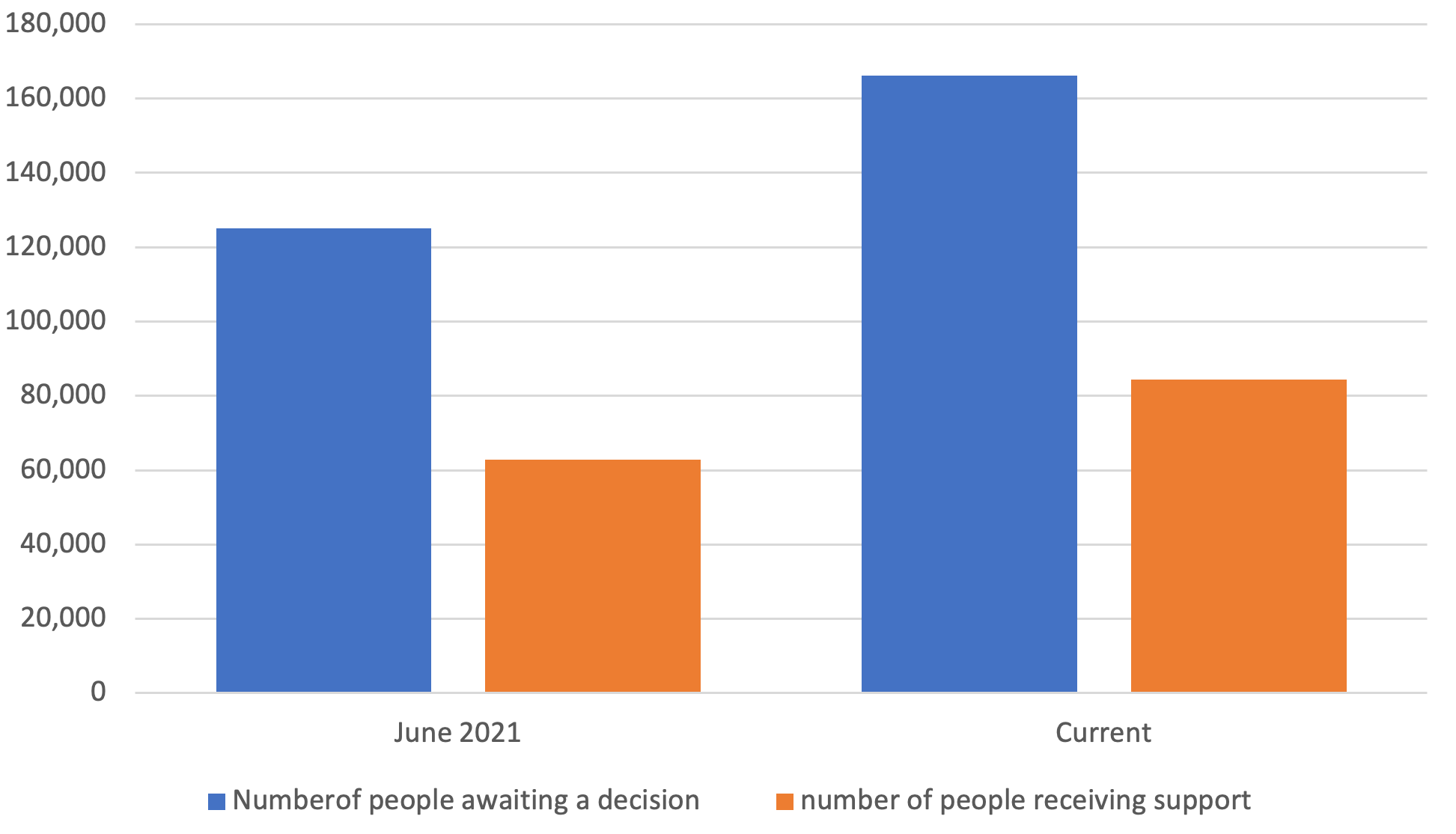

The Home Office “work in progress” caseload stands at 166,085, which is nearly double the figures in June 2020 and a significant increase since June 2021. The rate of increase in asylum applications compared to the rate decisions are being made shows that the situation is unlikely to improve soon for asylum applicants. In 2021, there were 56,495 new applications, but only 14,572 initial decisions were made. Currently, 84,457 individuals were housed in hotels or provided with monetary support, and that figure will realistically only continue to rise as the asylum backlog increases:

When asked what improvements are being made, Abi Tierney, the director general for customer services at the Home Office, confirmed that the department now has 1,073 decision-makers. This is an increase of 584, which has partially been helped by a recruitment and retention allowance. The attrition rate (i.e. staff leaving) has dropped by 31%. There has also been some restructuring between legacy work (clearing the backlog) and new work in progress. Tierney also confirmed other changes:

“We have been running a pilot in Leeds that looks at the time it takes to undertake interviews, and we saw in that pilot that our interview times have reduced by 37%, and that our decision-making at the same site has doubled per decision-maker per week. We are now rolling out that approach in Liverpool. The aim is that by May 2023, that simplified and more efficient decision-making approach will be applied right the way across the decision-making community.

Then the other piece is looking at technology. We are rolling out Atlas, which is a casework technology system, and looking at the whole experience for the service users. I think you used the word “chaotic” to describe the experience of some users in Manchester. We are looking at enabling them to access their case more easily online and book interviews – things like that. We are looking at that side of the system, too.”

David Neal, the Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration, emphasised that the Home Office should not just focus on expediting decision-making times; “[f]ine, you drive down to four decisions per decision maker per week, but if those are poor decisions, they will be challenged… at the tribunal… I think there is more work to be done in that regard”.

But Neal’s requests to meet the previous Home Secretaries were apparently not granted and the Home Office have shown little willingness to cooperate on the recommendations of previous reports published by the Inspectorate this year. Neal said he had given up writing to the Home Secretary. Whilst he intends to look into decision-making timings and effectiveness in asylum cases and other matters across the next year, it is clear that collecting evidence on these things is time-consuming in itself and may be ineffective if it is not then considered or utilised by the Home Office.

The resulting accommodation issues

The Manston processing centre in Kent was the subject of a significant number of the Committee’s questions and has subsequently made the headlines. The centre was designed to hold 1,600 Channel migrants for a short period of time. When it was first opened, the aim was to “hold migrants for up to five days”, and in the committee evidence last week O’Mahoney said people should be onsite for only around 24 hours. But at the last count earlier this week, roughly 2,800 migrants were being unlawfully held in overcrowded and dangerous conditions there. And this weekend, news reports claimed that around 1,000 more people arrived at the centre.

The short-term holding facility rules allow for individuals to be held in holding rooms for 24 hours and in holding facilities for not more than seven days. There are therefore potentially hundreds, if not thousands who have been detained illegally at the centre, with some there for up to four weeks. To put this into context, the numbers held at Manston is a larger population to manage and support than in any prison in the UK, and by staff that are not trained to do so.

The HM Inspectorate of Prisons has also published a report today, on the short-term holding facilities at Western Jet Foil, Lydd Airport and Manston. Unfortunately the report is dated August and so the facts and figures are already outdated by the evidence in the last week. At that time, the longest period of time spent at Manston was roughly 70 hours and the situation has deteriorated significantly since then. What the report usefully highlights is the lack of access to legal advice, and lack of formal procedure for recording the use of force and treatment by staff:

“3.5 Detainees were then searched in full view of others, including rub-down searches of women and children. Some staff were abrupt and impatient, including with children. We observed one member of Border Force staff pull a young child by the arm with no explanation to start the rub-down search…

…

3.11 Most detainees with identified vulnerability were not sent to Manston, but a few who were part of family groups had been held there, as it is Home Office policy not to split family groups unless absolutely necessary. This included wheelchair users, a detainee with severe mental illness who had been held before our inspection, and several victims of trafficking who were identified at Manston during our inspection. We spoke to Home Office and Mitie staff who had basic awareness of these detainees but could not provide evidence of coordinated care planning or specialist support in these cases.

…

3.16 Home Office data showed that no detainees had been designated as adults at risk at Manston despite individuals with significant health issues and experience of trafficking passing through the facility. This resulted in potentially critical information about vulnerability not being made clear to decision-makers at subsequent stages of the asylum process.”

After visiting the site last Monday, Neal said that Manston processing centre was no longer safe. He references a family living for 32 days on mats on the floor of a marquee and stated his concerns about fire, disorder and medical infections.

For example, reports of a diphtheria ‘outbreak’ were all but confirmed, though numbers remain low. Regarding the outbreak, O’Mahoney said, “I would not describe it as an outbreak…. We have very good health provisions [at Manston]. We have 24/7 coverage from paramedics and we also have doctors on the site every day”. And when asked what he would like to see being done by the returning Home Secretary, he confirmed that “[w]e are working as a department and across government to find accommodation to move people into as quickly as possible”. But this seems like a short-term and reactive solution.

The problem is exacerbated because the growth in the asylum backlog means there are no onwards housing options, so migrants cannot be moved on to more appropriate accommodation. The pipeline for finding hotel accommodation is apparently about two months because of commercial and value-for-money considerations. Community engagement and the location of hotels are also considered, to ensure those housed there can access public transport and local amenities.

But once in a hotel, the situation doesn’t improve. You can read more about the use of hotels for unaccompanied child asylum seekers here. The lack of adequate medical provisions or kitchen facilities and food mentioned, for example, is most likely a concern for all individuals housed in Home Office hotels.

Hotels are not a long-term solution. The cost of hotel use has soared to £5.6 million per day and is likely to continue to increase. And this doesn’t include individuals in the UK who have applied to one of the Afghan resettlement schemes. Housing Afghan nationals in hotels is costing an additional £1.2 million per day. Asides from costs, it is and always has been clear that housing vulnerable individuals in hotels is completely unsuitable; and it is a problem exacerbated by long periods of stay in hotels, and by individuals being moved around the country as hotels open and close. As stories continue to be published about Braverman attempting to avoid hotel use, the Home Office are apparently considering booking rooms across a number of hotels instead of reserving the entire hotel, in a response to tackle overcrowding at Manston with more urgency, though it is unclear how productive this would be, and what the safeguarding provisions of these agreements might be.

There are additional concerns about the use of enforcement officers to deal with the inevitable flare-ups and disruption at the centre, as individuals get bored with their situation. The power of immigration enforcement officers to draw a baton to restrain any individual is linked to their ability to enforce the immigration act. But in this situation, they are being asked to use them in a public order context, which is outside the powers granted to them by the asylum and immigration act.

Conclusion

There are at least two significant and troubling issues resulting from the evidence given at this committee hearing. The number of Channel crossings will not slow anytime soon and no deterrence or alternative tactic deployed by the government so far has helped decrease numbers or provide alternative safe routes into the UK. In 2021, November was the busiest month for Channel crossings and the numbers are expected to continue to increase.

And the consequence is more people entering the UK. This is something the Home Office either don’t want to address properly or doesn’t know how to accommodate adequately. Braverman has been accused of deciding to stop booking hotels for people in Manston processing centre, which has led to the current overcrowding and numerous subsequent issues. And O’Mahoney said that the situation at Manston is a symptom of a “creeping lack of ambition” from the Home Office that can also be tracked through the previous facilities at Tug Haven and the Western Jet Foil.

It is clear that the support and protection systems in place are less than adequate and solutions should be found in the short term to address the fundamental needs of asylum-seekers entering the UK. In the long term, the simple solution is to clear the ever-increasing backlog of asylum claims not only in a timely manner but in a safe and effective way. It is important to keep the Home Office under check as they try to find ways to achieve this.

One Response

I’m curious about where the “10,000 Albanians this year” figure comes from. If you look at the data the figure of Albanians arriving in the small boats Jan-Jun 2022 it’s less than 3,000?