- BY Colin Yeo

Tribunal reclaims jurisdiction to review deprivation of citizenship discretion

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

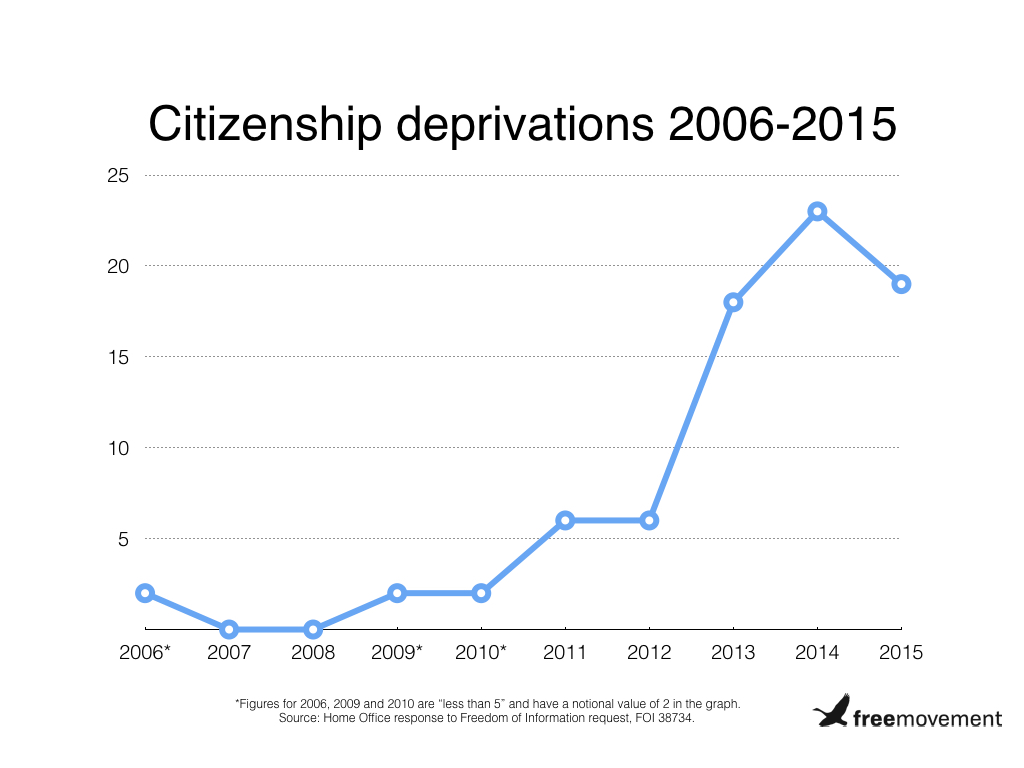

The number of cases of deprivation of British citizenship has risen sharply in recent years. For an in-depth look at the issues, see my earlier post on The rise of modern banishment: deprivation and nullification of British citizenship.

The increasing use of the power by the Secretary of State has led to more appeals. The number of appeals will surely increase further for two reasons, following on from the Supreme Court judgment in R (Hysaj & Ors) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2017] UKSC 82:

- Decisions which were previously dealt with as nullification cases, with no right of appeal, will in future mainly be dealt with as deprivation cases, which do carry a right of appeal; and

- There is a potentially large pool of cases previously decided as nullification cases which are now being reviewed by a team at the Home Office. In any of these cases the nullification decision will be replaced by a new deprivation decision, which will carry a right of appeal.

The Supreme Court decision in Hysaj basically declared a large number of previous nullification decisions unlawful, in effect quashing them. The Home Office has withdrawn many of these decisions. The effect on those concerned is probably that they are still British citizens today, no matter how long ago the nullification decisions were taken. If a deprivation decision is made, the person remains British throughout the process of challenging such a decision until the final order is made.

The effect of the retention of British citizenship on the current immigration status of recipients of nullification decisions and their family members is a very interesting issue.

[ebook 57266]This makes the latest decision of the Upper Tribunal on the issue of deprivation of citizenship all the more important. In the new case of BA (deprivation of citizenship: appeals) Ghana [2018] UKUT 85 (IAC), President Lane disavows the earlier decision by Vice President Ockelton in Pirzada (Deprivation of citizenship: general principles) [2017] UKUT 196 (IAC), which seemed to have been made in a vacuum without reference to other decided cases. Mr Ockelton has been described on this blog as a shirker rather than a worker when it comes to the tribunal’s jurisdiction. So it was in Pirzada, in which he seemed to suggest that the tribunal had no jurisdiction to review the Secretary of State’s exercise of discretion.

In BA the President holds that the tribunal can review the Secretary of State’s exercise of discretion, can substitute its own decision, can do so on material available to the tribunal even if it was not available to the Secretary of State and must also consider the consequences of the decision to deprive, including human rights grounds.

The official headnote reminds us of the basic principles in deprivation appeals:

(1) In an appeal under section 40A of the British Nationality Act 1981, the Tribunal must first establish whether the relevant condition precedent in section 40(2) or (3) exists for the exercise of the Secretary of State’s discretion to deprive a person (P) of British citizenship.

(2) In a section 40(2) case, the fact that the Secretary of State is satisfied that deprivation is conducive to the public good is to be given very significant weight and will almost inevitably be determinative of that issue.

(3) In a section 40(3) case, the Tribunal must establish whether one or more of the means described in subsection (3)(a), (b) and (c) were used by P in order to obtain British citizenship. As held in Pirzada (Deprivation of citizenship: general principles) [2017] UKUT 196 (IAC) the deception must have motivated the acquisition of that citizenship.

(4) In both section 40(2) and (3) cases, the fact that the Secretary of State has decided in the exercise of her discretion to deprive P of British citizenship will in practice mean the Tribunal can allow P’s appeal only if satisfied that the reasonably foreseeable consequence of deprivation would violate the obligations of the United Kingdom government under the Human Rights Act 1998 and/or that there is some exceptional feature of the case which means the discretion in the subsection concerned should be exercised differently.

(5) As can be seen from AB (British citizenship: deprivation: Deliallisi considered) (Nigeria) [2016] UKUT 451 (IAC), the stronger P’s case appears to the Tribunal to be for resisting any future (post-deprivation) removal on ECHR grounds, the less likely it will be that P’s removal from the United Kingdom will be one of the foreseeable consequences of deprivation.

(6) The appeal is to be determined by reference to the evidence adduced to the Tribunal, whether or not the same evidence was before the Secretary of State when she made her decision to deprive.

The facts of the case sound interesting: BA had been deprived of his British citizenship on the basis that he used multiple undeclared false identities, but was arguing that he had been working as a police informant and wanted to call a police witness. The evidence was to be heard in private, so it is unlikely we will learn the outcome.

If you want to gen up on citizenship deprivation, take a look at our online CPD training course on the subject.

SHARE