- BY Larry Lock

What is the difference between a “refugee” and an “asylum seeker”?

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Table of Contents

ToggleThis piece is about refugees, asylum seekers, and the Refugee Convention. It outlines who can be a refugee, and how being a refugee and having “refugee status” are two very different things.

We also explore the rights and entitlements available to refugees and to asylum seekers awaiting the outcome of their claim, and how these have changed over time. Finally, the piece considers how people can be excluded from benefitting from refugee rights under the Convention.

Refugees and the Refugee Convention

The relocation of refugees and asylum seekers dates back to the ancient customary “right of asylum”, under which the international community would provide protection to those forced to flee their home countries. In the 20th century these rights were formalised under international law into duties owed by states to those fleeing persecution and serious harm. The most important of these pieces of international law is the Refugee Convention 1951 and its 1967 Protocol.

The Refugee Convention is not UK immigration legislation. It is a piece of international human rights law, designed to remedy the problems that arise when people or groups of people can no longer rely on their state to protect their most fundamental rights. In this way it is unusual amongst other human rights law (such as the European Convention on Human Rights or ECHR) because of its palliative focus – that is, it deals with the symptoms of state-sponsored human rights abuse, and not its causes.

Who is a refugee?

A refugee is defined under the Convention as someone who has fled their country due to a “well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion”. Anyone, anywhere, who satisfies this definition is a refugee and therefore someone entitled to the rights and benefits set out in the Convention.

The definition itself is the subject of constant legal analysis globally, both in the courts and in academic study. With no international court supervising the application of the Convention — the way the European Court of Human Rights oversees how the ECHR is applied, for example — national courts across the world have committed to working together to find common ground. The judgments of higher national courts have a lot of influence over how the equivalent courts of different countries interpret the Convention.

Refugee status is declaratory

People who meet the Convention definition are automatically refugees, regardless of whether they are formally recognised as such. Paragraph 28 of the UNHCR Handbook illustrates this point:

A person is a refugee within the meaning of the 1951 Convention as soon as he fulfils the criteria contained in the definition. This would necessarily occur prior to the time at which his refugee status is formally determined. Recognition of his refugee status does not therefore make him a refugee but declares him to be one. He does not become a refugee because of recognition, but is recognized because he is a refugee.

This distinction between being a refugee and being recognised as a refugee is fundamental to the Convention. Being a refugee flows not from the grant of status but from the experience of the individual that was central to their claim. But a person must be recognised as a refugee in order to benefit from the Convention’s provisions.

This is the asylum claim – a request that the country of refuge provide for their rights as a refugee under the Convention. The asylum process is different in each country; the UK’s own process is set out here.

There are many thousands of refugees in the UK anxiously waiting for their asylum claims to be determined (often referred to as “asylum seekers”) and many others who have not yet made any asylum claim at all. That in no way makes them any less a refugee under international law – it just means their claim has not yet been formally considered.

What rights do refugees have under the Convention?

Refugees have rights under the Convention that, over time, the UK has incorporated into domestic law. These rights include the right to lawful stay in the UK, carrying with it the right to work, study, claim housing and welfare benefits, and access free healthcare. Refugees also have a right to reunite with partners and children under the refugee family reunion process.

Because refugee rights under the Convention are relatively generous compared to other forms of immigration status, states are often reluctant to grant people refugee status. In recent years, as asylum figures rose, political leaders played into far-right fears about “swarms” of migrants or “bogus” asylum claims made by people supposedly preying on Western hospitality.

As such, it can be a bit of a battle to get refugee status in the UK, with the Home Office not agreeing that the person falls within the Convention’s definition. Many have to rely on the appeal process.

Who is an asylum seeker?

As we have seen, refugee status is declaratory – the grant itself is not constitutive of being a refugee. But in order to gain refugee status, one must first claim asylum. An “asylum seeker” is someone whose claim for refugee status is being formally considered.

Countries have over time developed their own systems for processing asylum claims, recognising refugees and granting refugee status. What they have in common is that the asylum seeker cannot be returned to their home country whilst their claim is under consideration.

What rights do asylum seekers have under the Convention?

Very few. Asylum seekers have the right of entry into a country (under the Convention, but no longer in UK domestic law). Because they may indeed turn out to be refugees, the country has a duty to examine their claim and they cannot be turned back to their home country while this is going on.

Apart from this key protection, the Convention is largely silent on the rights of asylum seekers waiting for the outcome of their claim. As anxieties over border control have ramped up over the years, the rights of asylum seekers in the UK have become increasingly limited.

Under certain circumstances, the Home Office can decide that an asylum seeker can be held in immigration detention while their claim is processed. This is usually where a claim has been made at a late stage or the Home Office believes it to be false. The vast majority of asylum seekers are instead given immigration bail, which can come with restrictions on the person’s right to work or study, or require them to live at a specific location.

Asylum seekers are unable to access mainstream benefits. For those who can’t support themselves, financial support and accommodation can be provided under section 95 of the Immigration and Asylum Act 1999. The financial support is a bare minimum: £49.18 a week, with an extra £9.50 for babies under 1 year old and £5.25 for children aged 1 to 3 years old. If the accommodation provides meals then support is limited to £9.95 a week. The accommodation provided may also be appalling, and will nearly always be outside of London.

This is a far cry from what refugees are entitled to. Putting the inhumanity of it aside, there has always been a question-mark over whether treating “genuine asylum seekers” this way complies with the Convention. See for instance Lord Justice Simon Brown’s conclusions in JCWI v Secretary of State for Social Security [1996] EWCA 1293.

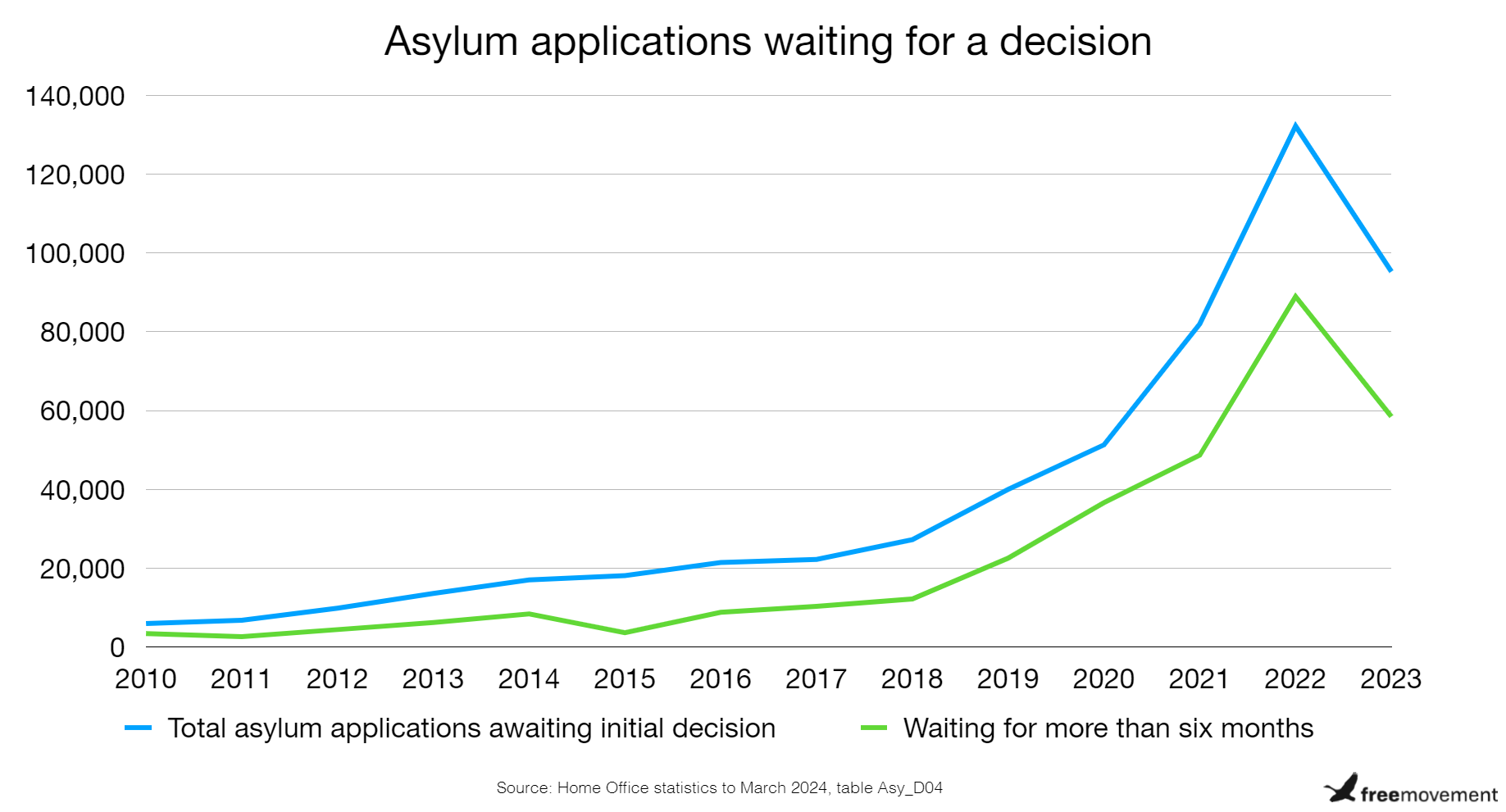

In any event, asylum support is meant to be a temporary measure while claims are under consideration. But asylum decisions are increasingly delayed, so many remain under these arrangements for a long time.

Who is not a refugee?

In everyday conversation, we often describe people forced to flee their homes as “refugees”. But the Convention definition is narrow and excludes many displaced people from its provisions. As an example, those fleeing natural disasters or climate change cannot benefit from the Convention.

There are some back-up forms of protection under international law. For instance, where someone falls outside the Convention’s remit, but there are substantial grounds for believing they face a “real risk of serious harm” on return to their home country, they will automatically be considered for a grant of humanitarian protection.

There is also fundamentally a cross-border element to the definition of a refugee – you must be outside of your home country. Those who fled their home but remain within their country’s borders are still the “responsibility” of their national government. They are defined as Internally Displaced Persons to whom the Convention does not apply.

Who cannot be a refugee?

Some refugees are excluded from benefiting from the Convention, such as those who are found to have committed war crimes or “crimes against humanity” under Article 1F of the Convention. More usually however those who have committed a “particularly serious crime” (defined as one with a sentence of twelve months or more) are excluded under section 72 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

Those who fall foul of these provisions are still refugees if they still fear persecution in their home countries. But their exclusion from the Convention means that they are no longer entitled to the rights that flow from refugee status.

Cessation of refugee status

People can also stop being a refugee, as it were. if they no longer meet the Convention definition. This is known as “cessation” of refugee status. The Convention sets out the general circumstances where this can happen.

For instance, someone will no longer be a refugee if they have voluntarily returned home or re-availed themselves of their country of origin’s protection, such as by returning home. Cessation can also occur where the situation that gave rise to the well-founded fear of persecution no longer exists.

Cessation of refugee status is a relatively new problem. Throughout most of the Convention’s lifetime, the UK has respected the rights of refugees to build their new lives in the UK. Before 2005, refugees would be allowed to settle in the UK straight away, without needing to apply for any further leave. As such, cessation of refugee status was not an issue – if refugee status was given then it was given for good and not normally taken away.

Over time, the right to settlement has been restricted. The Home Office has ceased to let refugees settle in the UK from the outset. It instead grants a fixed period of five years’ leave (uncharitably referred to as a “probationary period”). Once the five years is up, a refugee must then apply to settle in the UK; applications can be refused. The effect of this is undoubtedly a more precarious existence and an intrusion on the building of a permanent life.

The UK has also introduced “safe return reviews” to work out whether someone is still a refugee or whether the cessation clauses apply. Where cessation applies, the Home Office is no longer bound by the Convention and can in theory return the person to their home country. While this is relatively rare in practice, it is another limit to the generosity of Convention rights.

This article was first published in June 2020 and has been updated by Sonia Lenegan.