- BY Chris Desira

New statement of changes to the Immigration Rules: HC 170

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Table of Contents

ToggleAnother statement of changes to the Immigration Rules (HC 170) was laid on 24 October 2019. The changes relate to Appendix EU of the Rules and their functioning in a no-deal Brexit scenario.

This is somewhat surprising given recent events. Jacob Rees-Mogg said in Parliament on the same date that there is no impediment to a general election because no-deal has been taken off the table. It is rather cheeky to introduce a set of Rules relating to a no-deal scenario that is looking increasingly unlikely to occur.

Anyhow: as they relate to a no-deal scenario, most of the changes take effect on 31 October 2019, with the most of the remainder taking place on the date that the UK withdraws from the European Union.

For chapter and verse, you can access pdf copies of the explanatory notes or the full statement of changes.

In summary, the changes include:

- For family members joining European residents after Brexit to be able to rely on past periods of residence in the UK that occurred before Brexit as part of the relevant five-year continuous period for settled status

- Establishing the European Temporary Leave to Remain Scheme. This allows European citizens and their family members moving to the UK after Brexit to be able to lawfully reside in the UK beyond 1 January 2021. This section appears in a new Part 2 of Appendix EU, with the older Rules relating to the EU Settlement Scheme moving into a new Part 1

- Applying UK conduct and criminality thresholds to European citizens and their family members moving to the UK for the first time after Brexit in order to “increase security and better protect the public”

- Making reference to the Immigration (Amendment) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019 laid before Parliament on the same day. These make no-deal changes to the EEA Regulations 2016, which will be retained, for the time being, by the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018

- Changes to the rules relating to Turkish businesspeople and their family members.

Save for the changes relating to Turkish citizens, which will be a topic of a later blog post, we will explain these changes below in more detail. Bear in mind that these changes relate to a no-deal scenario. Different rules would apply in a deal scenario, as we would then be within the terms of a withdrawal agreement and a transition period.

Family members

The changes ensure that certain family members who move to the UK after Brexit will be able to rely on that new residence period when applying for pre-settled status and settled status. This applies to the spouse, civil partner or durable partner of a European citizen, or anyone in the ascending or descending lines of the European citizen or the spouse or civil partner. Only these family members can move to the UK after a no-deal Brexit has occurred.

Essentially, their time residing in the UK from entry can be counted towards the five-year residence period required to achieve settled status.

[ebook 90100]There might be instances where these family members have previously resided in the UK but join the European citizen after Brexit. In such instances, it would be fair for that previous residence to count towards settled status. The changes to the Rules allow for this, so long as they make their application for pre-settled or settled status before 31 December 2020 (which is the deadline for all applications under the EU Settlement Scheme in a no-deal Brexit).

If they fail to do so, or their reasons for the late application are not considered good enough by the Home Office, their residence period will begin from the date they re-joined their European family member. So they can still achieve settled status, but it will take longer to do so.

The deadlines by which these family members will need to come to the UK to fall within the EU Settlement Scheme will be:

by 29 March 2022, where the relationship existed before Brexit and continues to exist when the application is made, in the case of spouses, civil partners, durable partners, children, parents and grandparents, and of children born overseas after Brexit; and

by 31 December 2020, where the relationship as a spouse, civil partner or durable partner was formed after Brexit and continues to exist when the application is made, or from other dependent relatives.

Appendix EU (Family Permits), the route that family members need to use to initially enter the UK to join their European sponsor, has been amended to allow for non-European family members to apply for a family permit where the relationship was formed after Brexit. Once in the UK on a family permit, the person will then need to apply under the EU Settlement Scheme.

There’s also this new thing called an “EU Settlement Scheme Travel Permit” which is not an Appendix EU Family Permit. It is for non-EEA family members who lose their Biometric Residence Permits abroad.

European Temporary Leave to Remain

This scheme, which will become operative only in a no-deal Brexit, will enable European citizens and their close family members who move to the UK for the first time to lawfully reside in the UK beyond 31 December 2020.

The European Temporary Leave to Remain Scheme will grant a non-extendable 36 months of leave to remain. If the person wants to stay in the UK beyond those 36 months, they will need to make a further application and qualify under a new immigration system planned to be in place from 2021.

If they qualify under the new system for a route that leads to indefinite leave to remain (‘settlement’), then time spent on a European Temporary Leave to Remain permit will be counted towards the qualifying residence period for settlement. So it makes practical sense for individuals to apply for the European Temporary Leave to Remain Scheme as soon as possible. That said, if it turns out that they cannot stay on under the new system, they will have to leave the UK sooner.

The application must be made in the UK. It will be free of charge and involve “a simple online process” to confirm nationality, identity, and undergo security and criminality checks. This suggests that the existing online process for the EU Settlement Scheme will be adapted to include European Temporary Leave to Remain applications.

An interesting part of the eligibility is that a person granted European Temporary Leave to Remain must have adequate accommodation for the duration of that leave. It is unclear how this is going to be policed.

From 4 December 2019, if a non-European family member is already lawfully in the UK (in any capacity other than as a visitor) they can apply for European Temporary Leave to Remain. If successful, they will be granted the same length of leave as the European family member. So, sensibly, it allows for in-country switching, and will not require the family member to return home and reapply from abroad.

Deportation rules

The changes on criminality will allow the Home Office to apply UK conduct and criminality thresholds to European citizens and their family members who move to the UK for the first time after Brexit. This, in essence, allows for removal for more minor offences or conduct than is permitted in EU law.

Rules on deporting EU citizens today

At the moment, where a European national commits a crime in the UK and is sentenced to a term of imprisonment, they can be deported in the following limited circumstances:

- If they have lived in the UK for less than five years, they can be deported only where their conduct represents a genuine, present and sufficiently serious threat affecting the fundamental interests of society

- A person who has lived in the UK for five years or more and has acquired a right of permanent residence, then their conduct must present serious grounds of public policy and public security. In other words, their offending must be much more serious

- A person who has lived in the UK for ten years or more needs to show the highest threshold for removal: imperative grounds. This means that it is extremely difficult to deport them

Any decision to deport an EU citizen must also be proportionate, which means the decision-maker must consider all other factors of a person’s life in the UK, such as age, state of health, family, economic situations, cultural integration, links to the country of origin and rehabilitation, amongst others.

In essence it should really be quite difficult to deport a European citizen under EU law so long as the Home Office is acting lawfully.

Rules on deporting non-EU citizens would apply instead

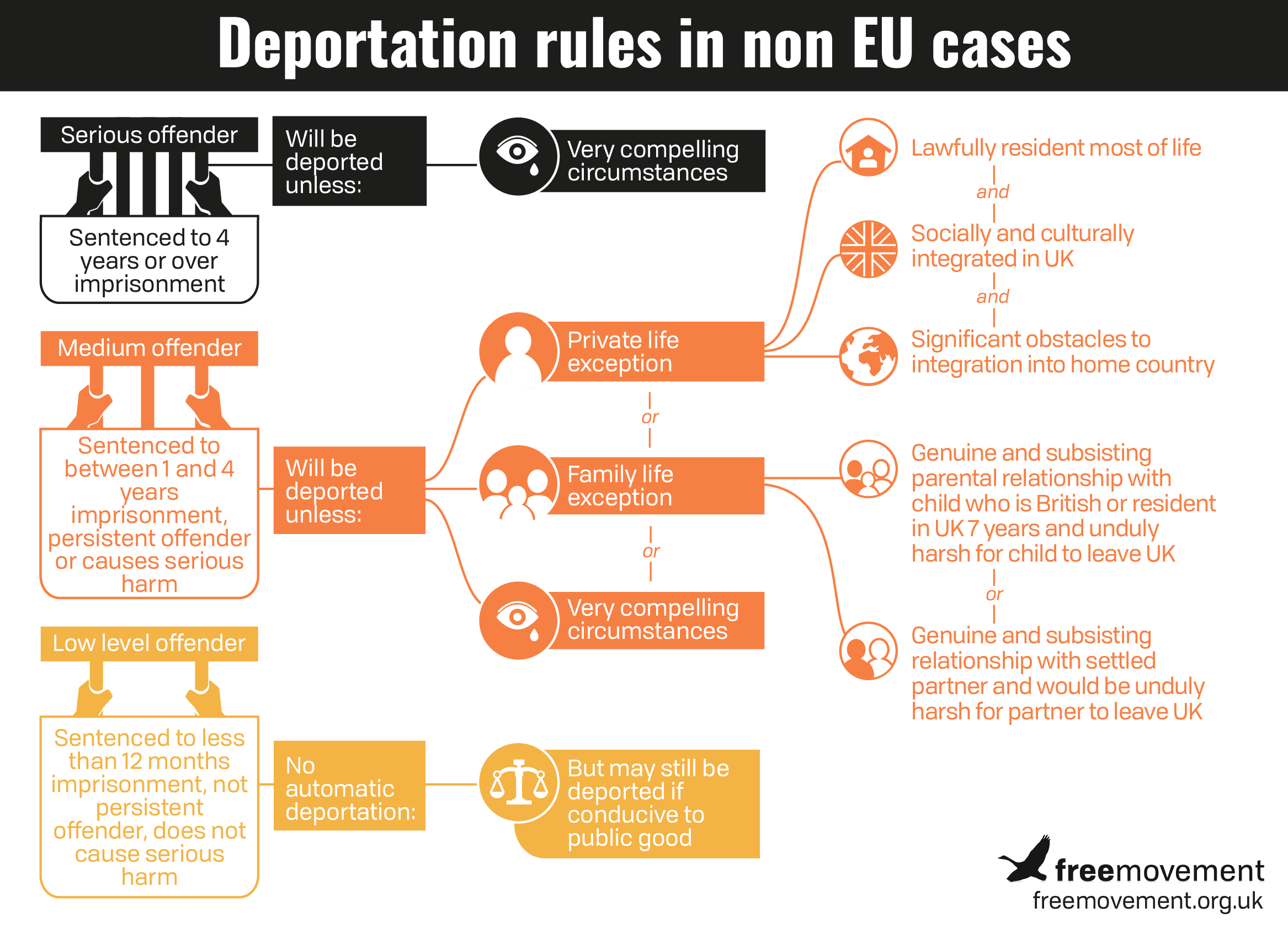

The UK standards on deportation for non-EU citizens offer far weaker protections compared to EU law. They are even more complex, as summarised in our favourite infographic:

It is these UK rules that will apply to European citizens who come to the UK for the first time after Brexit or, if they were residing in the UK prior to Brexit, acquire new criminal convictions from 31 October 2019.

The changes introduce another scenario: where the criminal act occurs before Brexit, but the sentence for imprisonment comes down after Brexit. This could only be allowed if no-deal actually occurs. In a deal scenario, this would be incompatible with the withdrawal agreement.

A European person resident in the UK for 10 years, arriving when he was a child. He was caught in possession of a crack pipe, drug weighing equipment and a kitchen knife. He received a non-custodial sentence including a community order and fines.

Under EU law this would not be enough to amount to serious grounds of public policy or public security and the Home Office would not be able to justify removal.

Under UK law, it will be possible to remove him from the UK on these facts.

This change will not apply to nationals of Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland, because it will be incompatible with their separate citizens’ rights agreements agreed with the UK. Conduct before Brexit will continue to be considered under EU law thresholds, regardless of the timing of the sentence.

Now one might have little sympathy for someone causing or looking to cause trouble, but we are all one act or accident away from being in the same situation. A teenager from a less well-off background associating with the wrong group, a person with mental health problems living on the streets, or one’s attention drawn away briefly while driving, could be all that it takes to be removed from the UK.

It will be important for European residents and their family members to be aware of these thresholds so if they are unlikely enough to find themselves falling within them they know to seek legal assistance.

Immigration (Amendment) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019

These regulations makes changes to the Immigration (European Economic Area) Regulations 2016, which will be retained in UK law by the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018.

This ensures that much of the free movement framework will remain in place in a no-deal UK until Parliament passes primary legislation to repeal it. The changes to the 2016 Regulations include the application of UK thresholds on conduct and criminality to “increase security and better protect the public”, and to reflect the above changes.

Clarity and transparency

This statement of changes continues the approach of making a wholesale substitution of Appendix EU rather than specifically identifying each change. The only possible way of identifying each change is by using a text comparison website to compare, by copying and pasting line by line, the content of the statement of changes with the current version of Appendix EU (you’re a hero, Chris – Ed.).

Whether by design or otherwise, this makes understanding what is happening much more difficult than necessary.

Combined with the fact that it is the second statement of changes in the last six weeks, this makes it extremely difficult for lawyers in this field to provide reasonably accurate and up-to-date advice, let alone for individuals affected to know what is happening. Good law is meant to be accessible and easily understood without legal assistance, so that those affected are able to access reliable, clear information on their rights and duties. The frequency and method of delivering these changes, and the increasing complexity of Appendix EU, makes this an impossible task.