- BY Nicholas Webb

New Home Office “lines to take” in Sudanese asylum claims

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Table of Contents

ToggleThe Home Office now believes that the Sudanese country guidance cases should no longer be followed, based on a change of country circumstances. Its “lines to take” now argue that while non-Arabs are likely to be at risk in the Darfur region, not all are at risk in the capital Khartoum and relocation may be possible depending on the particular facts of the case.

Although “lines to take” are considered to be privileged information, in a recent case the Presenting Officer made submissions by reading them out, referring specifically to the lines to take documents. I have transcribed the submissions and they can be found here or downloaded as a Word document here.

So what is does the current case law on Sudan say?

The case the Home Office seeks to overturn is AA (Non-Arab Darfuris – relocation) Sudan CG [2009] UKAIT 56 The tribunal in that case decided, to quote the head note:

All non-Arab Darfuris are at risk of persecution in Darfur and cannot reasonably be expected to relocate elsewhere in Sudan. HGMO (Relocation to Khartoum) Sudan CG [2006] UKAIT 00062 is no longer to be followed, save in respect of the guidance summarised at (2) and (6) of the headnote to that case.

For a country guidance case it is remarkably short, running to only eight paragraphs. The reason for this brevity: it was based on a concession contained in a Home Office Operational Guidance note (see paragraph 4).

The next country guidance case, MM (Darfuris) Sudan (CG) [2015] UKUT 10 (IAC), dealt with the definition of “non-Arab Darfuri”. Was it a geographical term referring to area or origin, or a term describing a particular ethnicity? The Upper Tribunal, after considering expert evidence, concluded that the Sudanese authorities classify non-Arab Darfuris on the basis of ethnic origin, and not geographical location.

The most recent country guidance case is IM and AI (Risks – membership of Beja Tribe, Beja Congress and JEM : Sudan) (CG) [2016] UKUT 188 (IAC). The case did not engage significantly with AA or MM as the appellants had not claimed to be Darfuri, or that claim had been rejected by the First-tier Tribunal below. The Upper Tribunal, dealing with the risk for political opponents of the regime, concluded there was no general risk but that all factors would need to be considered to assess whether an individual would be at risk.

As can be seen from the lines to take, it appears the Home Office wish to extend this type of analysis to non-Arab Dafuris in Khartoum. But at present AA is still good case law and suggests all non-Arab Darfuris are at risk of persecution and should be granted refugee status on the basis of ethnicity alone.

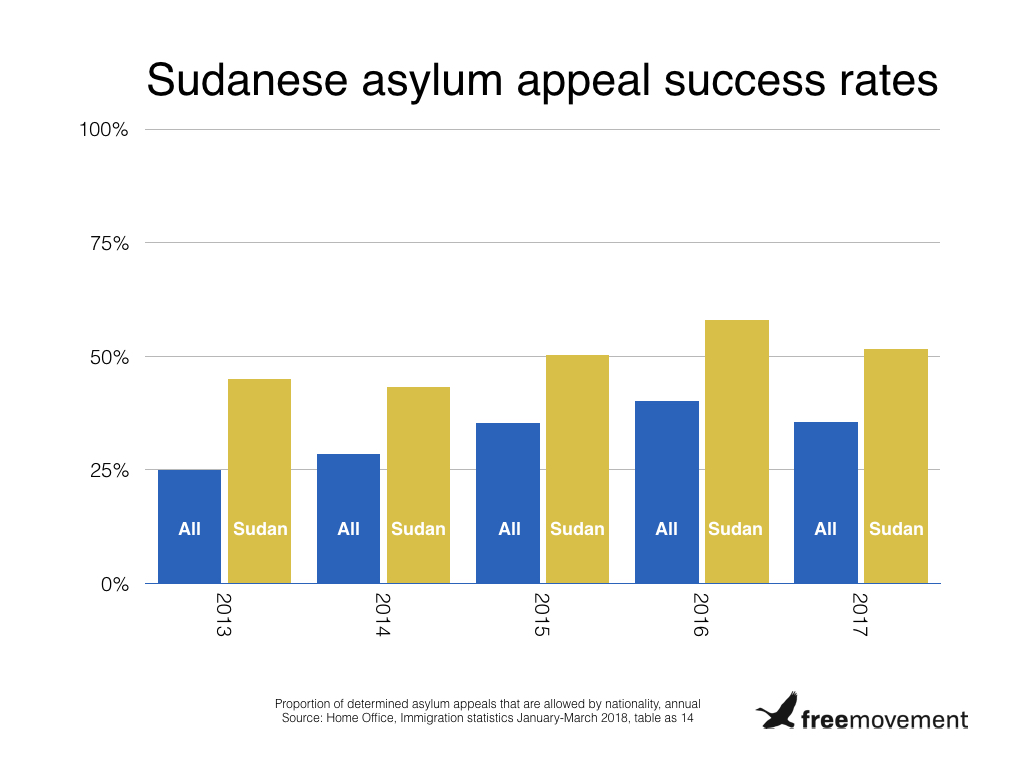

Over the past five years, 8,000 Sudanese citizens have applied for asylum in the UK (not including dependants). This includes a rising number of unaccompanied children: 337 in 2017, up from 32 in 2013.

Over three quarters of Sudanese applicants were granted asylum at the first time of asking, compared to just over one third of asylum seekers generally. On top of that, the appeal success rate has been over 50% in each of the last three years. The average is around 35%-40%.

The status of country guidance cases

It will be an error of law to not follow a country guidance case without good reason to do so. The Tribunal Practice Direction at paragraph 12 tells us that much. If further authority were required, Lord Justice Stanley Burnton LJ sitting in the Court of Appeal provides it in SG (Iraq) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2012] EWCA Civ 940:

a Country Guidance determination of the Upper Tribunal (Immigration and Asylum Chamber) remains authoritative unless and until it is set aside on appeal or replaced by a subsequent Country Guidance determination.

Of course, the Practice Direction does give the First-tier Tribunal some room for manoeuvre to depart from a country guidance case. The Upper Tribunal endorsed the following approach in DSG & Others (Afghan Sikhs: departure from CG) Afghanistan [2013] UKUT 148 (IAC).

A country guidance case retains its status until either overturned by a higher court or replaced by subsequent country guidance. However, as this case shows, country guidance cases are not set in stone (see also HS (Burma) [2013] EWCA Civ 67), and a judge may depart from existing country guidance… decision makers and tribunal judges are required to take country guidance determinations into account, and to follow them unless very strong grounds supported by cogent evidence, are adduced, justifying their not doing so. To do otherwise will amount to an error of law.

It is however important to emphasise that to depart from a country guidance case the tribunal must only do so if it has evidence.

What evidence does the Home Office rely on?

So far in those cases I have seen the Home Office has not provided much, if any, evidence to back up its stance. Not even the documents relied upon in the “lines to take” have been provided to the tribunal. One would think that this is litigation 101.

However, it would appear the Home Office is relying on the following evidence:

- Situation of Persons from Darfur, Southern Kordofan and Blue Nile in Khartoum, a joint report of the Danish Immigration Service and the Home Office

- The latest Country Policy and Information Note on Sudan: Non Arab Darfuris

- The British embassy letter referred to in IM and AI at paragraphs 67 and 68

This post is not the place to forensically analyse this information and to identify evidence in rebuttal, but in the meantime forewarned is forearmed. Knowing the Home Office approach is likely to assist practitioners in these cases.

And of course this blog will be sure to report the result when the Upper Tribunal wrestles with the new position and the evidence on which the Home Office seeks to rely.