- BY Paul Erdunast

How not to support a victim of human trafficking: a demonstration by the Home Office in R (FT) v SSHD

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

The Upper Tribunal overturned several decisions concerning the grant of Discretionary Leave to Remain to a victim of human trafficking in FT, R (on the application of) v the Secretary of State for the Home Department [2017] UKUT 331(IAC). The background to the case is that of the Home Office failing to appropriately identify the individual concerned as a victim of human trafficking, and subsequently unlawfully placing him in immigration detention for four years.

The facts of the case are stark. After a childhood of regular beatings with rods and belts by his mother and his alcoholic father, his uncle borrowed money from people traffickers to send him to the United Kingdom. The Upper Tribunal describe his initial period in the United Kingdom in the following terms:

The applicant remained under the control of the traffickers and was compelled to work, under threat of violence and without remuneration, in a ‘cannabis house’ where he was locked in and held in debt bondage. On one occasion, having asked to leave, he was threatened with a knife and a gun and his arm was cut causing extensive bleeding and leaving a scar.

He was arrested on suspicion of cultivating cannabis in 2007, at which point he gave a statement to the duty solicitor disclosing several indicators of trafficking: debt bondage to the tune of £17,000, the lack of a wage for his work, and concern about what may happen to his family if the debt was not repaid.

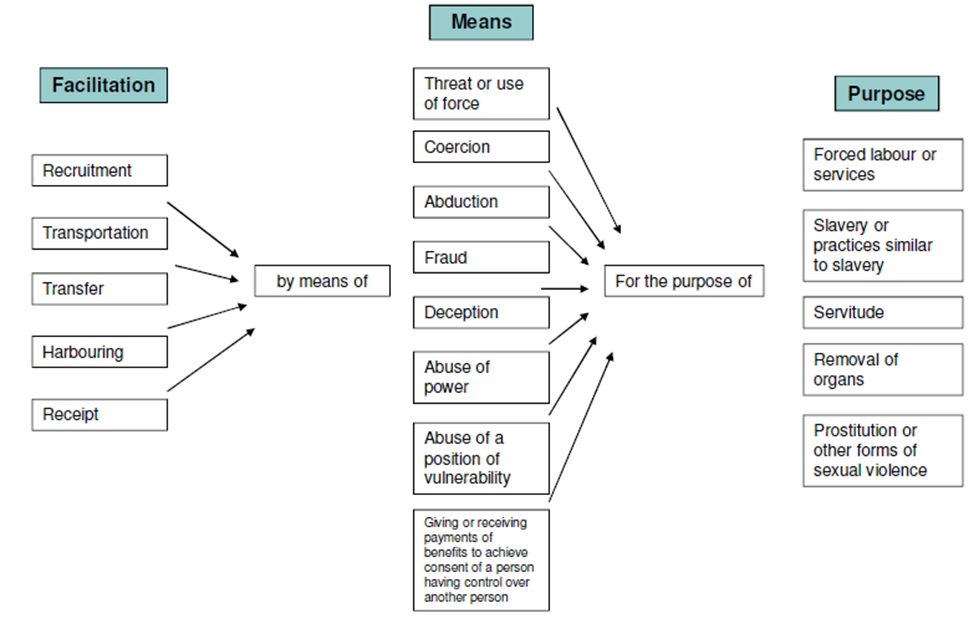

The above image represents the definition of human trafficking given by the Council of Europe Convention on Action Against Trafficking in Human Beings of 2005, augmented by Article 2.3 of Directive 2011/36/EU (credit: AIRE Centre: ‘Upholding Rights! Early Legal Intervention for Victims of Trafficking’). Spotting a victim of trafficking such as the individual in question should not be rocket science: even at this early point his statement should at least have raised the possibility that his case fit all three elements of the definition.

None of this was disputed by the Secretary of State in the present case. The Secretary of State indeed candidly accepted that the repeated failures to consider trafficking when he was imprisoned for cultivating cannabis, during his asylum claim, placed in immigration detention for almost four years, and after that was placed in NASS accommodation with electronic tags and a curfew.

Only six years later, on 15 August 2013 was he referred to the National Referral Mechanism for the purpose of identifying him as a potential victim of trafficking. Yet this did not stop the Secretary of State making two decisions in 2014 finding that the applicant was not a victim of trafficking, which ended outreach and financcial support that had been provided for him. Even after a later decision in 2014 that the applicant was a victim of trafficking, no further leave was granted to him, his deportation was pursued, and no steps were taken to reinstate his support. This was despite submissions which included a letter by a counsellor at Room to Heal confirming that the applicant attended a lengthy assessment, that he was severely isolated and had great difficulties trusting people, and that he would be well suited to the kind of therapeutic program provided by the organisation.

After these decisions were successfully judicially reviewed, a fresh decision granted the applicant discretionary leave for six months, and revoked the deportation order. Six months was viewed as an appropriate length of leave to grant the applicant, despite the expert evidence stating as follows:

For individuals with the applicant’s complex psychological presentation the expert recommended a service specialising in the treatment of complex trauma presentations which may require at least 40 sessions of treatment [up to two years of treatment].

Additionally, it was not disputed in the present case by the Secretary of State that the medical evidence clearly indicated that such treatment cannot effectively or ethically be initiated until the applicant feels that he is in a stable and secure position – this being impossible with only six months of Discretionary Leave.

All the above was deemed as relevant by the Upper Tribunal, which quashed the decisions to grant six months of Discretionary Leave to Remain, because the relevant circumstances of the mishandling of the applicant’s case were not taken into account, nor were sufficient reasons given for the decision. The Upper Tribunal remitted the decision to the Secretary of State to remake lawfully.

The duration of leave is ultimately a matter for the respondent, but her decision must lawfully reflect the matters identified in this judgment including the protracted history of this litigation, the applicant’s clear vulnerability, the unchallenged recommendations in the medical evidence and her own conduct.

The applicant had suggested that Indefinite Leave to Remain was the only rational decision open to the respondent, but this was rejected by the court, which considered that his case was not so exceptional as to clearly satisfy the very high barrier to a grant of indefinite leave to remain: rather, that the decision is a matter for the Secretary of State, but that it should be for a sufficient length of time to adequately reflect the matters pointed out by the judgment. Hopefully for the applicant, this entails a sufficient amount of time for him to feel stable, and enable him to start his therapy.