- BY Kat Langley

How much influence does the media have over the hostile environment?

Table of Contents

ToggleOne month into the job, it’s clear that Suella Braverman is good at making the headlines. However, some of her rhetoric may seem familiar. The government’s hostile environment policy is well-rehearsed and the media has played a significant and long-term role in developing the rhetoric that we see today. It is undoubtedly being used as a political tool to promote the hostile environment dialogue we have grown so accustomed to. But how is this affecting public opinion, or the choices of those looking to travel to the UK as a migrant or refugee?

Where did it all begin?

The Windrush scandal is a startling example of the hostile environment, dating back to the 1940s. Arguably, anti-immigration sentiment has been increasing since this time. The hostile and racist sentiment is further reflected in the common media portrayal of the migrant as a criminal or terrorist. There is a poor understanding of the distinction between refugees and migrants and, in reality, there should be little difference in how the two groups are treated. With both groups, racial and cultural differences are quickly inflamed and exploited by the media. There should be recognition in the media, and by extension, the public, that the standard refugee is not necessarily a criminal or a terrorist, and that the standard migrant is not necessarily stealing someone’s job or failing to integrate into society.

The media today

The hostile environment policy may have expanded in recent years as Conservative party politics has drifted further to the right. What is not yet clear is how successful the most recent policy aims will be, and how large a role media rhetoric plays in our view of whether the policy has in fact made any progress or positive impact.

For example, the well-known Rwanda deal is yet to have any success, with all removals on hold, pending ongoing legal challenges. The visible difficulties with this policy have now been admitted by Braverman, who confirms that it is unlikely anyone will be sent to Rwanda this year. Instead, the Home Secretary has turned to attack lawyers that work in the immigration sector. Only a few days ago, she ordered an inquiry into the work done to train Home Office staff, by immigration law trainers, because they were also involved in legal challenges blocking flights to Rwanda.

And the government hasn’t pressed pause on the anti-immigrant sentiment more generally which, most recently, comes in the form of ongoing attacks on particular sections of the migrant population. Albanian nationals have been accused of faking trafficking and modern slavery claims, and Indian nationals have become a target group for reduced business migration, being accused of staying in the UK beyond their visa expiry dates.

It is problematic to gather information about the number of refugees and migrants who have been deterred from the UK, or the number of people that have gone underground once in the country, as a result of rhetoric like this. Without larger-scale empirical research, it is also impossible to accurately take the temperature of public perception of immigration. The consensus in my research (not yet published) is that the public is divided almost equally between those who support refugees and those who perceive them as a threat. And these perceptions are largely driven by information churned out by the media, and the stock phrases used by those media outlets, thereafter relied upon by politicians to discuss immigration policy.

The importance of accurate story-telling

The language used in the mainstream media when covering stories about migrants vividly mirrors the existing narrative of the migrant as “the other”, and it continues to shape the narrative by doing so. Perhaps the clearest articulation of anti-immigration sentiment can be found in written journalism.

Examining 43 million words (the total content addressing migration in 20 popular British newspapers) between 2010 and 2012, a 2013 report by the Migration Observatory, found that the most common word used in relation to “migrants” was “illegal”. Headlines like “Eight-fold increase in the number of illegal migrants entering Europe” are typical. “Failed” turned out to be the most common descriptor of “asylum seekers”. To describe security concerns and aspects of the legality of migration, words like “terrorist” and “sham” were most used.

Small boat crossings are commonly referred to as outright illegal, and “illegal channel crossings” might be one of the most commonly used phrases in migration news this summer. But the legal issues are far more complex. It’s from within this setting that the statistic that around 60% of people arriving in the UK on small boats this summer were Albanian, has been repeated several times. And once in the UK, Albanian nationals have been accused of “exploiting the modern slavery law loophole”.

It is worrying that information like this are being published regularly, without the corroboration of relevant legal expertise, or official Home Office data. It is now admitted that the statistic may only be correct on particular days. However, the suggestion across a number of media outlets, that the figure was representative of the number of arrivals across the whole summer and that false modern slavery claims were regularly being made, seemed to be used to try to prop up a Home Office scheme to fast-track removals of Albanian nationals. This type of rhetoric and misinformation is not new, but it’s clearly still being used to drive unprecedented policies.

How much is our attitude affected by the media?

The kind of language used in the media criminalises migrants who often cross borders in vulnerable circumstances. Politicians like Theresa May used their public platform to push a radical and divisive agenda. It could be classed as little more than political grandstanding when Priti Patel announced the Rwanda scheme. And Suella Braverman pledged to ban Channel crossing altogether, which seems like perfect media fodder. On the business immigration front, it is hard to see how the announcement that Braverman wants to restrict the number of foreign students who can stay in the UK after finishing their studies in order to slash immigration numbers, won’t deter individuals considering applying for university places in the UK.

These are perfect discussion topics, and they make for easy headlines. But media fodder does impact public perception and, in turn, the policy aims of the politicians involved. Several studies have found evidence of a positive correlation between media coverage and attitudes towards migrants, where extensive news coverage contributes to the success of populist rhetoric and the rise of anti-immigrant sentiment. There is a long-standing argument that the media has a heavy influence over public opinion of refugees, and the media have “constantly conflated asylum with crime, terrorism, illegality, fraud and worse”. As a result, refugees are marginalised and scapegoated.

In research on EU attitudes, Italians (57%), Greeks (56%) and Britons (48%) were found to be most in favour of more restrictive asylum policies, while Germans, Spaniards and Swedes tended to say that their asylum policies were either about right or should be less restrictive:

“In the EU press, the negative commentary on refugees and migrants usually only consists of a reported sentence or two from a citizen or far-right politician – which is often then challenged within the article by a journalist or another source. In the British right-wing press, however, anti-refugee and migrant themes are continuously reinforced through the angles taken in stories, editorials, and comment pieces.”

While these patterns cannot be attributed exclusively to media reporting, research for UNHCR has demonstrated that the kind of media messages found in the British press sample – repetitive, negative, narrow and derogatory – can be highly influential.

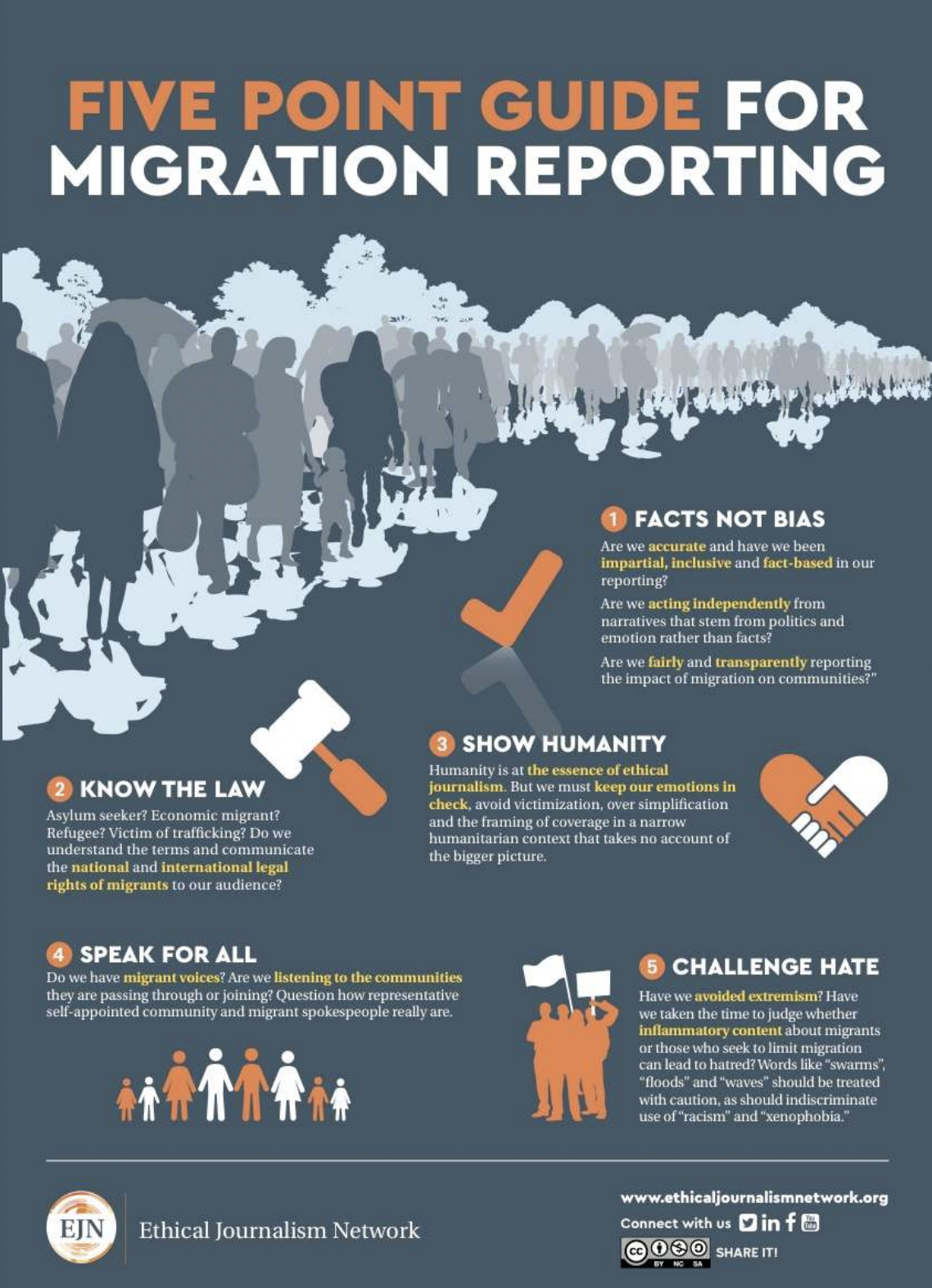

The issue is more complicated than all mainstream media are evil, but the media are accountable for influencing public opinion across a spectrum of society from newspaper readers and online media to television and radio. These influences, in turn, drive the importance of the hostile environment policy in the eyes of the public. Perhaps more media outlets should take note of the guidance from the ethical journalism network.

What are the consequences?

Undoubtedly, media portrayal has a significant impact on refugees. But there is more than a perception problem. The tightening of immigration controls within the UK, and the portrayal of immigration rules in the media, is leading some asylum seekers to take risks, and previously law-abiding individuals feel compelled to take illegal action. Many go “underground”, overstay their visas, or start working illegally to support themselves whilst awaiting a decision on their leave to enter or remain in the country.

The problems surrounding language and public opinions are conflated by the media. Ultimately, it is the government that is responsible for inciting and participating in the anti-immigration rhetoric. After all, the will of the many is driven by the might of the few. Political leaders in both destination and origin countries might pay lip service to goals such as combating illegal migration while doing little to introduce or enforce immigration restrictions in practice; either because they lack the capacity to do so or because they derive economic and political benefits from certain migration policies.