- BY Alex Schymyck

Deportation appeal not a “dress rehearsal” says Court of Appeal

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Lowe v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2021] EWCA Civ 62 is about the role of the Upper Tribunal in deportation appeals. The role of an appellate court when reviewing the findings of fact made by the court below sounds straightforward: it will only intervene if the findings are irrational or perverse on the basis of the evidence. But applying that apparently clear principle in practice can be messy. The split Court of Appeal in this case illustrates how.

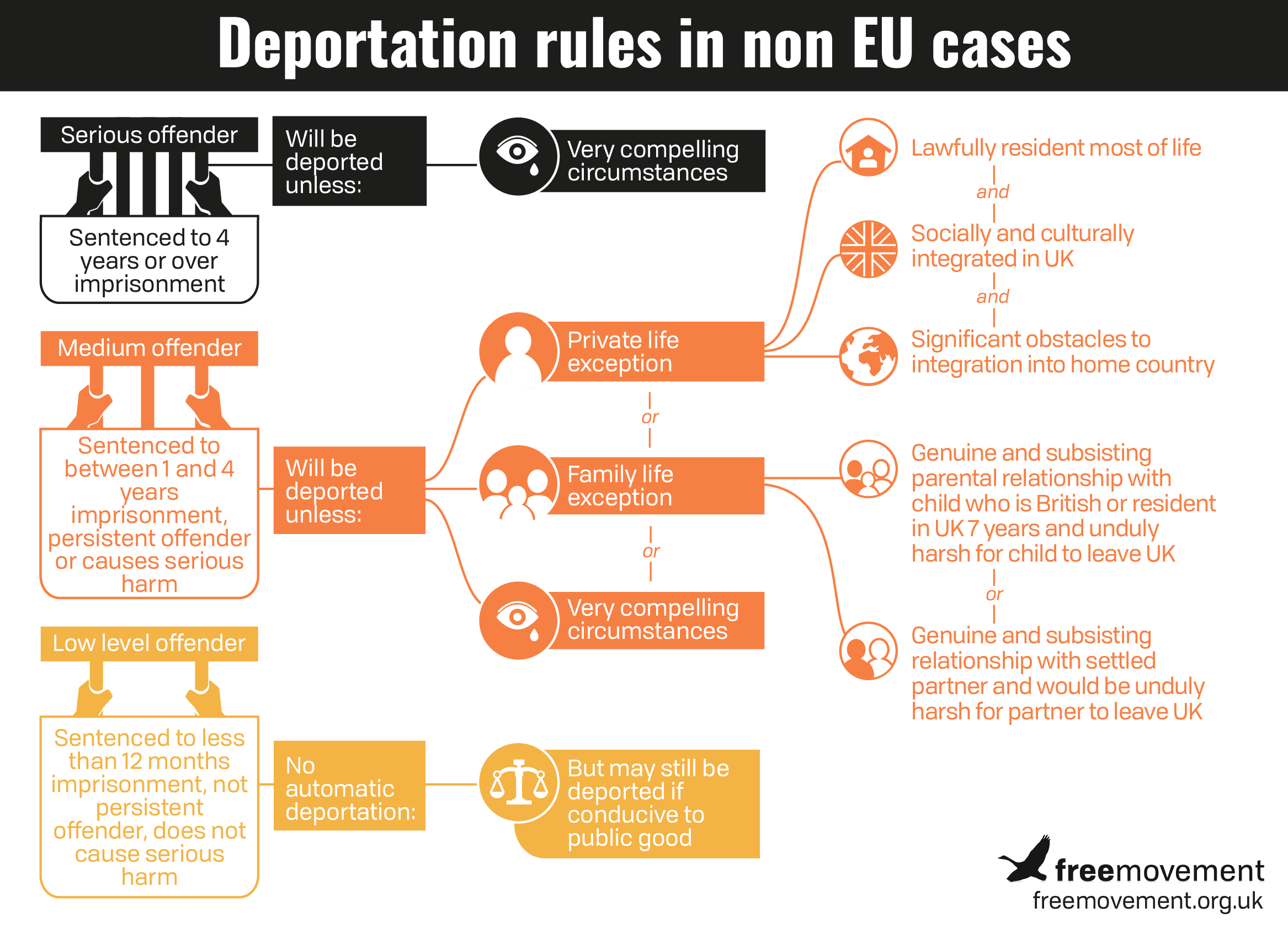

The underlying issue in the deportation appeal was narrow. The appellant had been sentenced to less than four years in prison and sought to rely on the “private life” exception to deportation. As shown below, one of the requirements for availing of that exception is that there are “very significant obstacles” to reintegration into the person’s home country (Jamaica, in this case).

The only dispute was whether Mr Lowe would in fact face very significant obstacles to reintegrating. He had left Jamaica at the age of three and lived in the UK ever since, so on the face of it there were good reasons to think that such obstacles existed. The First-tier Tribunal thought so, allowing Mr Lowe’s appeal against deportation. The Upper Tribunal reversed that decision.

In the Court of Appeal, Mr Lowe challenged the Upper Tribunal’s decision on the grounds that the judge had merely substituted his own view rather than identifying that the First-tier Tribunal decision had been irrational. The majority of the court agreed:

In this case, the FTT had determined the issues that were before it, being those which were regarded as being central to the question of whether the Appellant had demonstrated the relevant “very significant obstacles”. It was not necessary for the FTT to deal with a case that was not being made by the Respondent. The appeal to the FTT was “the first and last night of the show”, not a “dress rehearsal”.

…

It was, in my view [Lord Justice McCombe, with whom Lady Justice Asplin agreed], quite open to the FTT judge to find that there were the necessary very significant obstacles based on the impression made upon him as to the effect of the “exile” of this young man, with all his characteristics, attributes, qualities and defects that were disclosed by the evidence.

…

It is not surprising to me that a judge (if not all judges) would find, as this judge did, that there were very significant obstacles to integration. Others might have made a different decision, but this was very much a case on its own facts to be assessed on the evidence.

But Phillips LJ dissented:

The UT judge asked himself whether those factors were capable of amounting to very significant obstacles, or whether they were not so capable, so that the FTT judge’s conclusion was not one he was entitled to reach (in other words, a perverse or irrational decision). In my judgment that was a proper question as a matter of law. The UT judge was not substituting his own assessment of the evidence, but considering whether the evidence passed the threshold for the conclusion reached. In that context the UT cannot be criticised for pointing out that certain matters, which might have demonstrated that there were very significant obstacles, were not advanced by the Appellant (such as difficulty in finding accommodation or employment).

The division within the Court of Appeal illustrates how the apparently clear principle that an appellate court should only intervene to correct irrational factual findings is much less clear when applied to a real case. The judgment is a strong defence of First-tier Tribunal judges, although by reining in the oversight provided by the Upper Tribunal it risks greater inconsistency in decision-making.