- BY Nick Nason

The Curious Case of the Eritrean Country Guidance

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

‘[I]t has to be said, Asmara does not feel like the capital of a country generating asylum applications with a 85% grant rate’ (sic)

– Informal Home Office report of UK visit to Eritrea, 9-11 December 2014

In 2014, nationals of Eritrea were the second largest group of asylum seekers in the European Union. Thousands of Eritreans continue to reach the UK each year. The contents of guidance used by the Home Office to determine such claims and the manner in which that guidance is compiled is therefore of crucial importance, impacting directly on many lives.

Executive reversal

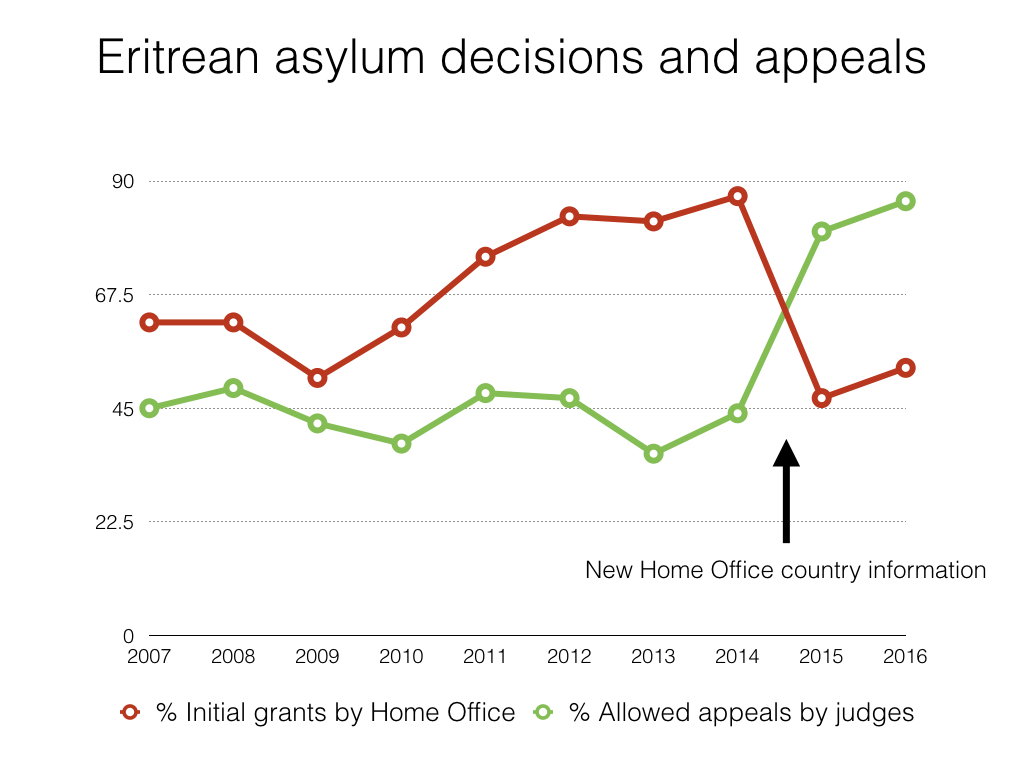

In March 2015, the Home Office reversed aspects of its position on who should be eligible for refugee status from Eritrea. In particular, it released new guidance stating that Eritreans fleeing national service ‘who left illegally are no longer considered per se to be at risk of harm or mistreatment amounting to persecution on return’. This new guidance had two very serious consequences.

Firstly, in the year ending March 2016, the grant rate for Eritrean asylum applicants fell through the floor, dropping from 86% in the year ending March 2015 to 42% in the year ending March 2016. Secondly, and as a result of this much lower grant rate, the government was able to argue in November 2016 that Eritrean children should not be included in the group of unaccompanied minors brought over from Calais under the Dubs agreement. This was because, in the end, the government allowed entry to nationals of countries with a grant rate of 75% or more.

Given the ramifications of this change in policy for thousands of people, the Home Office must have been relying on some pretty strong evidence…

The pretty strong evidence

As with all great sagas, it began in Denmark.

In August and October 2014 a group of Danish immigration officials undertook a ‘fact-finding mission’ to Eritrea. The aim of this mission was to better establish and evaluate the risk criteria for Eritreans in the event of return, in particular for those who had fled the country illegally rather than completing national service.

On 25 November 2014, the mission reported that ‘the Eritrean government’s attitude towards national service seem[ed] to be more relaxed’ and that it was ‘possible for evaders and deserters who have left Eritrea illegally to return if they pay [a] two per cent tax and sign [an] apology letter at an Eritrean Embassy’. The Danish Immigration Service changed its policy to reflect the findings made in this report.

Shortly after its publication, Amnesty International condemned the report as ‘completely absurd’. Human Rights Watch said it was ‘deeply flawed’. The expert upon whose testimony much of the report was based, Professor Kibreab, publicly disassociated himself from it in early December 2014. Two of the three writers of the report, Drs Olsen and Olesen, publicly criticised the summary section and conclusions drawn by the third (supervising) writer, which were based on their input and research.

Following criticism of the report, the Danish authorities backtracked. In December 2014, the Danes announced that they would continue to recognise as refugees Eritreans fearing persecution as a result of their illegal exit and/or desertion or draft evasion and that ‘this might well involve providing the benefit of the doubt to the asylum-seeker’ and that it expected to recognise such asylum claims in ‘many cases’.

New guidance

Notwithstanding the widespread and sustained criticism of the report, and the admissions made by its authors and contributing expert about its reliability, the Home Office released guidance in March 2015 relying almost entirely on the findings of the Danish report. In response to criticism in November 2015 by the Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration, who suggested that the Home Office should not rely on any part of the Danish report, the Home Office stated in a short response that they simply did not accept that the work of the Danish fact finding mission had been discredited.

The consequences of this Home Office change of policy were immediate, halving the number of asylum grants to Eritreans in the year following the new guidance.

However, although the guidance to caseworkers had changed, this was not binding on the courts which hear appeals against refusals of asylum claims. The number of appeals lodged by Eritrean nationals against rejected claims rose from 224 in the year ending March 2015 to 1,760 in the year to March 2016. Of appeals determined in the year ending March 2016, 85% of those by Eritrean nationals were successful.

This meant, in short, that the judges were also unimpressed by the Danish report, and the government’s reliance upon it.

UK Fact-Finding Mission

Despite their confidence in the reliability of the Danish Fact-Finding Mission and its resulting report, a delegation from the United Kingdom took it upon themselves to visit Eritrea and make their own report. This was also partly to address issues identified and raised by the Upper Tribunal, which had by this time agreed to hear an Eritrean country guidance case. Members of the UK mission were in Asmara, the Eritrean capital, for two weeks in February 2016.

In a visit almost entirely coordinated with, and reliant upon, the Eritrean government, and in what some might consider to be a textbook example of confirmation bias, the report of the UK fact-finding mission closely reflected the post-2015, Danish inspired guidance. The central contention, as confirmed by government sources in the country, was that the Eritrean state was much more likely to refrain from persecuting returnees who had evaded the draft and/or exited the country illegally if they were prepared to pay a 2% diaspora tax and/or sign a letter of regret that they had done so.

Don’t call it a comeback

The tribunal considered all of these matters in MST and Others (national service – risk categories) Eritrea CG [2016] UKUT 00443 (IAC), a behemoth of a Country Guidance case, as reported previously on freemovement. While conceding that extracting reliable information from such a closed society was incredibly difficult, the court found that the position of the Home Office was essentially unsupported by the weight of the evidence. They found that the information collected during their Eritrean mission was gathered under the auspices of the Eritrean state, and should therefore be treated with caution. The tribunal also found that, anyway, ‘the evidence did not come anywhere close to establishing that the payment of the tax and the signing of the letter would enable draft evaders and deserters to reconcile with the Eritrean authorities’ [334].

After the outcome of the Country Guidance case, the Home Office readjusted its guidance to reflect the position which had existed prior to the Danish fact finding mission. Eritrean applicants are now broadly in the same position as they were in prior to March 2015. This was, of course, too late for the minors left across the channel, and for the hundreds of applicants forced to engage in the stress and expense of an appeal, as well as the costs to the public purse of a having to hear them.

It is particularly galling that, in the end, the Secretary of State did not seek to rely on the main findings of the 2014 Danish report (see paragraph 179 of MST).

Executive recklessness?

Recklessness involves conduct where the actor does not desire harmful consequences, but foresees the possibility, and consciously takes the risk anyway.

It does not require a sophisticated legal mind to imagine that it would have been in the interests of the Eritrean government to play down their own poor human rights record. Nor would it be surprising if, in return for aid, the government of Eritrea were prepared to promise change. It calls into serious question the judgement of an organisation normally so reluctant to take individuals at their word.

Documents originally obtained by the Public Law Project, reported by the Guardian and seen by freemovement, include summaries of high level meetings between UK and Eritrean government officials in 2014. The documents record conversations and views which seem to place the cart of aiming to reduce ‘irregular migration’ before the horse of actually having the evidence which might support it.

The impression given is that the minds of officials were already made up in 2014, based on a ‘deeply flawed’ report, a desire to reduce Eritrean numbers, and blind instinct: ‘Asmara [did not] feel like the capital of a country generating asylum applications with an 85% grant rate’.

The behaviour of the Home Office in this episode falls somewhere on a spectrum from Panglossian optimism and/or methodological incompetence at the most generous end, through to knowingly or recklessly changing country guidance for political reasons without the required evidence base at the other.

The conversations reported in the documents obtained by the Public Law Project, their reliance on the widely discredited Danish report, and the findings by the tribunal in MST that their evidence came nowhere close to supporting the change in policy, tend to invite a less charitable view of Home Office conduct in this matter, and raise serious questions about the political neutrality of UK government Country Policy and Information Notes in the future.

SHARE