- BY CJ McKinney

£1,000 child citizenship fee found unlawful

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

The High Court has ruled that charging a citizenship fee of over £1,000 to children is unlawful. The decision will be widely welcomed by campaigners who have long argued that the fee charged to register a child as British, which is set far above the administrative cost of processing applications, is “pricing children out of their rights”.

The challenge succeeded only on the limited ground of failing to assess children’s best interests, meaning that the Home Office could maintain the current fees after taking that step, or perhaps introduce a limited scheme of fee waivers. But the claimants are trying to take the matter to the Supreme Court in order to get a more substantial verdict on the lawfulness of the fee. The case is R (The Project for the Registration of Children As British Citizens & Ors) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2019] EWHC 3536 (Admin).

Children charged £1,000 to exercise citizenship rights

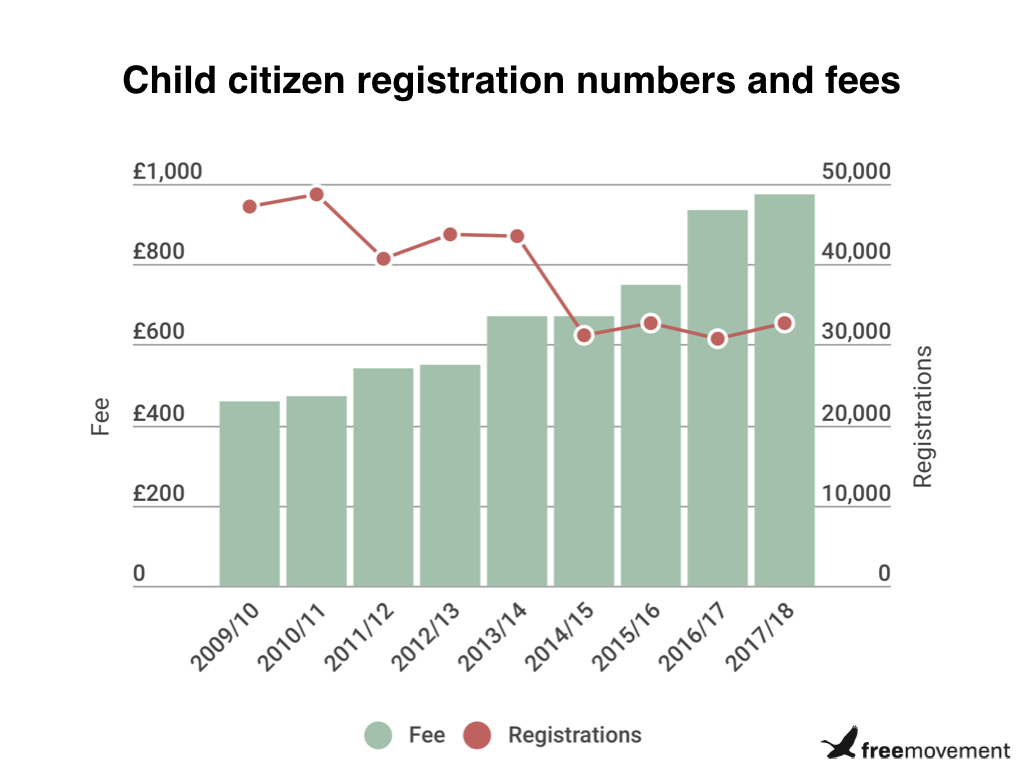

Many children born in the UK or living here from an early age do not actually have British citizenship, but can get it through a process called registration. Processing applications for registration costs the Home Office an estimated £372, but it charges applicants £1,012. Analysis carried out by Free Movement last year, and not disputed by the Home Office, found that the surplus on child registration fees amounted to almost £100 million between 2012 and 2017.

Mr Justice Jay said the evidence before him showed that “for a substantial number of children a fee of £1,012 is simply unaffordable”. That includes the two children in whose name the case was taken, O and A. 12-year-old O was born in the UK and has never left the country, but is not a British citizen. She is entitled to register, but her mother can’t afford it. In O’s own words:

I was born in this country and have lived here all my life. I feel as British as any of my friends and it’s not right that I am excluded from citizenship by a huge fee.

I want to be able to do all the things my friends can. I don’t want to have to worry they will find out I don’t have a British passport and think that means I am not the same as them.

Three-year-old A would be entitled to automatic citizenship if not for the fact that her mother is married to someone other than her father; her family can’t afford the registration fee either.

As Jay J said, children without citizenship are “in an obviously precarious position, and in addition to their risk of being removed or deported have limited or no access to the welfare state”. But the registration fee had been unsuccessfully challenged before, in Williams [2017] EWCA Civ 98. The decision in Williams closed the door on some of the legal arguments. In particular, the claimants failed on the argument that the fee was so high as to make the right to register impossible to realise in practice.

Failure to consider children’s best interests

A different argument did land. Section 55 of the Borders, Citizenship and Immigration Act 2009 instructs the Home Office to consider the best interests of children in immigration, asylum and nationality cases. Jay J found, in short, that the Home Office had not bothered to weigh up the best interests of children in making the fees policy:

there is no evidence in the voluminous papers before me that his client [the Secretary of State] has identified where the best interests of children seeking registration lie, has begun to characterise those interests properly, has identified that the level of fee creates practical difficulties for many (with some attempt being made to evaluate the numbers); and has then said that wider public interest considerations, including the fact that the adverse impact is to some extent ameliorated by the grant of leave to remain, tilts the balance.

Sir James Eadie QC for the Home Office argued that Parliament had considered, and rejected, attempts to lower the fee. It was therefore not for the courts to interfere. But the court found that “nowhere on the Government’s side” in these debates “has there been any recognition of where the best interests of children might repose”.

Jay J rejected an argument based on the Equality Act 2010, however, saying that “impecuniosity is not a protected characteristic”. Nor did he quash the relevant fee regulations, granting instead a declaration that they are unlawful unless there is a best interests consideration process under section 55.

Solange Valdez-Symonds of the Project for the Registration of Children as British Citizens said:

It is significant that the court has recognised British citizenship is the right of these and thousands of children and that the consequences of blocking their registration rights is alienating and harmful.

While that recognition is a great step forward, the fact remains that tens of thousands of British children are growing up in this country deprived of their rights to its citizenship, including by this shamelessly profiteering fee.

The High Court has granted a certificate to the claimants to apply directly to the Supreme Court for permission to appeal on the point they lost on. It has also granted permission to appeal to the Home Office. In the meantime, there is no immediate basis for those who have paid a registration fee to be refunded. There may eventually be a case for refunds, though, particularly if the fee is ultimately reduced.