- BY Paul Erdunast

Annual Report of Tribunals highlights urgent areas for improvement

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Table of Contents

ToggleThe Annual Report of the tribunal system has been published. The review of the First-tier Tribunal Immigration and Asylum Chamber review starts at page 74. The First-tier report tells of long waits caused by fluctuations in caseload, a long-term change from salaried to fee-paid judges and with it a loss of expertise, and a need to record more hearings. The Upper Tribunal report is largely positive, with output exceeding input for the first time.

Long waits at the First-tier Tribunal

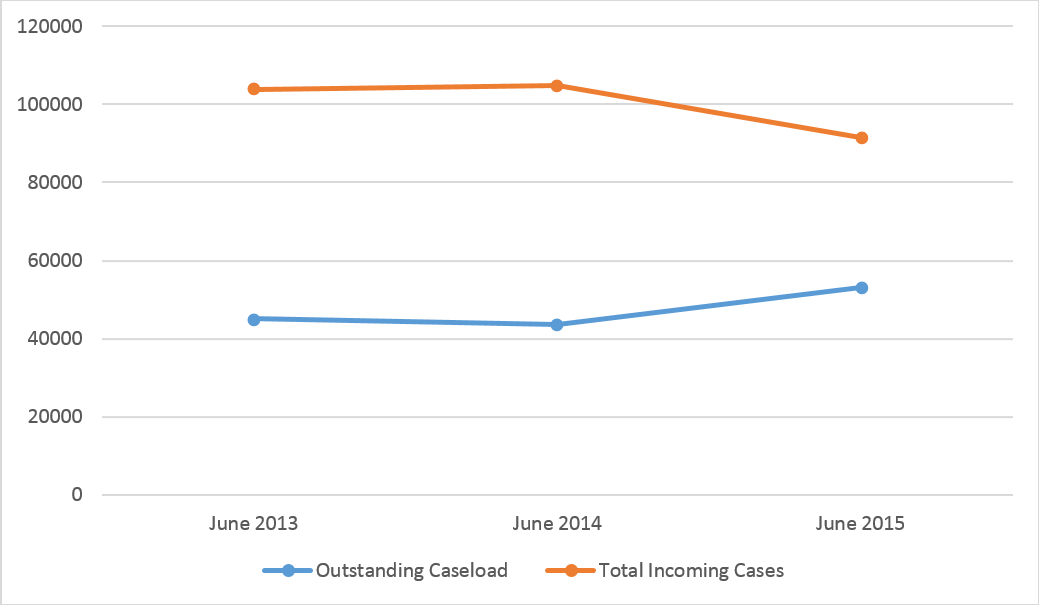

The President of the First-tier Immigration Tribunal, Judge Michael Clements, reveals that fluctuations of workload in ‘boom and bust’ cycles have led to outstanding caseload figures of 52,991 in June 2015 – as opposed to 43,643 in June 2014 and 45,043 in June 2013. This is compared to figures of 91,612 in June 2015, 104,980 in June 2014 and 103,923 in June 2013. It is these cycles that take the blame for what appears to be lower efficiency this year compared to previous years, given the lower total incoming cases but a higher backlog.

Mr Clements acknowledges this as a problem, including for overall morale. The ‘boom’ cycles which cause delays are not the only problem; the ‘bust’ cycles where there are few sittings mean that judges become ‘de-skilled’, and so less able to deal with cases that arrive on their desk each day. He tells us that he is working on a solution, which he will soon give an announcement on.

It cannot be denied that these fluctuating cycles are a serious problem which must be acknowledged. It is something about which it can be fairly said in an annual report that the IAC “could do better”.

Strategy of moving from full-time salaried to part-time fee-paid judges

Furthermore there appears to be evidence of a long-term judicial strategy change represented by a switch from full-time salaried judges to fee-paid immigration judges. In October 2005 there were 152 salaried judges compared to 94 in October 2015. These have been largely replaced by 197 fee-paid judges who have been inducted into the Immigration and Asylum Chamber from the Social Entitlement Chamber and the Employment Tribunal. This, rather than the employment of more full-time judges. This change to disposable part-time positions means more flexibility and less commitment for a Ministry of Justice that has needed to make severe financial cuts to the legal system. The effect of this strategy is “the loss of an immense amount of judicial expertise and experience”, without it being properly replaced like-for-like.

One might also have thought that this move to a more flexible but arguably de-skilled workforce would at least be compensated for by being capable of ready deployment to deal with varying levels of work, but apparently not.

All in all, the President of the First-Tier Immigration Tribunal is fair in his assessment of where the Tribunal stands in relation to salaried judges being replaced by their fee-paid counterparts. He frankly deals with the challenges it faces, and the improvements it needs to make.

Emerging from the cave? Technology in the First-tier Tribunal (again)

Mr Clements hopes for more tribunal proceedings to be recorded and technology to be improved in the coming year. It is no surprise to Free Movement that the technological poverty of the Immigration Tribunal has been flagged up. This blog has already passed comment on the stone-age approach of the Tribunal reflecting the inability to be remotely conversant with video-link technology. It will be a welcome surprise if dramatic improvements are made as a result. Furthermore, Mr Clements hopes that the impact of the Detention Action case, which rendered decisions made under the 2014 “Fast Track” Procedure Rules unlawful, will be further rationalised this year.

In addition, he draws attention to the difficulties faced by judges when dealing with cases where the appellant is either not in front of them or unrepresented. An appellant would not be at the tribunal if they have been removed from the UK and are attending an out-of-country appeal. This blog has already commented on the practical unfairness of out-of-country appeals. They psychologically enable the judge to engage less on an emotional level when the appellant is on a screen rather than in their room, and it will cost money to bring them back.

The immigration jurisdiction has always made high demands on the judiciary’s “judgecraft”. New provisions inserted into the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 have substantially reduced the rights of appellants to “in country” appeal hearings. This means that, increasingly, judges are being required to hear appeals where the appellant, having been removed from the UK, is not present in front of them. Further, when an appellant is present, he or she may well be unrepresented.

Unfortunately unrepresented cases are becoming the norm owing to legal aid cuts. It is hard enough for a judge to engage with a represented claimant through an interpreter, where their representative understands the law. It is even more difficult with an unrepresented claimant. It must be the case that appellants who would have succeeded if they were represented are, without that benefit, rejected. This is a large-scale denial of justice, but one which cannot be got rid of or appealed, as the provisions limiting legal aid and appeal rights are legal, even if unpalatable.

All appears well in the Upper Tribunal, alongside large-scale retirement and recruitment

For the first time since Immigration Judicial Reviews were transferred from the High Court to the Upper Tribunal, output has exceeded input. Mr Justice McCloskey, President of the Upper Tribunal (Immigration & Asylum Chamber) also noted that numbers of appeals have not dropped, despite the forecasting that they would. Mr Justice McCloskey rightly emphasises that in this light, the statistics on judicial review output are even more impressive.

Several Upper Tribunal judges have retired, and more will retire in the coming year, or will start working part time. This by necessity calls for a major recruitment exercise. The wheels appear to be turning already…

Their departure will give rise to a further recruitment exercise and the necessary planning has already begun. Furthermore, the attractions of part-time working continue to be evident. Several Judges of the Chamber have reduced, or will presently reduce, their hours.

It is for immigration practitioners everywhere to hope all these developments are made as soon as possible, especially those relating to technology. This would mean that out-of-country appellants do not face the doubly uphill struggle of being absent from the hearing and being unable, owing to lack of practicality, to provide live video link evidence.