- BY John Vassiliou

Getting an adult dependent relative visa is hard but not impossible

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Table of Contents

ToggleAdult dependent relative visas have one of the highest refusal rates of all immigration routes. Between 2017 and 2020, 96% of applications were refused. In this article I look at why these applications often go wrong and what you can do to try make them go right.

This is not a template for success. It is intended as a general guide to help you help the Home Office make the right decision.

What is an adult dependent relative visa?

The relevant immigration rules used to be in Appendix FM but are now in Appendix Adult Dependent Relative. In addition, the Home Office publishes a guidance document for caseworkers.

Before we get into what this visa is, let’s be clear what it is not. This is not simply a parent visa. This is not simply an elderly person’s visa. This is not a visa for retired people of independent means. This is not a visa for financially dependent but otherwise healthy parents. An adult dependent relative visa is something considerably more than all these things.

Adult relative of a UK sponsor

The meaning of “adult” and “relative” is clear enough. The applicant must be an adult over the age of 18, and the applicant must be either the parent, grandparent, child, or sibling of the sponsor. In the case of parents and grandparents, it is permissible for both them and their partner to apply together, even if only one member of the couple meets the dependency criteria.

The sponsor must be either a British citizen, settled in the UK, have protection status, or be an EEA national with pre-settled status that was granted not on the basis of being a joining family member (i.e. they have leave granted under EU3 of Appendix EU by meeting condition 1 of EU14).

Dependency

The meaning of “dependent” is where things get complicated. There are two limbs to the definition of dependency in Appendix Adult Dependent Relative:

ADR 5.1. The applicant, or if the applicant is applying as a parent or grandparent, the applicant’s partner, must as a result of age, illness or disability require long term personal care to perform everyday tasks.

ADR 5.2. Where the application is for entry clearance, the applicant, or if the applicant is applying as a parent or grandparent, the applicant’s partner, must be unable to obtain the required level of care in the country where they are living, even with the financial help of the sponsor because either:

(a) the care is not available and there is no person in that country who can reasonably provide it: or

(b) the care is not affordable.

The first of these criteria is tough. Many elderly relatives will not meet even this one. But it is the second criterion that makes it very, very difficult to succeed with these applications.

Long term personal care to perform everyday tasks

The starting point for any application is proving an applicant for an adult dependant relative visa needs long term personal care to perform everyday tasks. “Long term” must be more than just temporary. The clearest explanation of this that I could find is now over ten years old and comes from Upper Tribunal Judge Grubb in the unreported case of Timo Nour Osman v The Entry Clearance Officer – Riyadh OA/18244/2012:

30. No definition of “long-term personal care to perform everyday tasks” is contained within the Immigration Rules. The reference to “personal care” is to be distinguished from “medical” or “nursing” care and would appear to mean that the care that has to be provided is “personal” rather than, for example, support provided by mechanical aids or medication. The need is for “personal” care, in other words, care provided by another person. The “personal care” must be required “long-term” rather than on a temporary or transitional basis. And, further, the provision of care must be necessary in order that an individual may perform “everyday tasks”.

Everyday tasks can include everything one needs to get by in daily life: think about washing, dressing, cooking, feeding, cleaning, shopping, exercising, going outside, or even companionship. An applicant may not need help with all of those, but at least some of those must be engaged otherwise this is a non-starter.

I’ve emphasised going outside and companionship because these aspects of daily living are often overlooked as aspects of personal care. People are social creatures and loneliness and isolation are often big contributors to declining health.

The long term personal care must be required because of at least one of either age, illness or disability. I have never encountered a situation where all three factors have been absent so I’m not sure exactly what would happen in such a scenario, but let’s assume an application would be refused.

In approaching this limb of the dependency definition you should ensure that when you explain the care needs, you take time to explain how or why these care needs have arisen.

Unable to obtain the required level of case in the country where they are living

With long term personal care needs established, the next hurdle is establishing that the adult dependant relative is unable to obtain the required level of care in the country where they are living, even with the financial help of the sponsor, because either the care is not available and there is no person in that country who can reasonably provide it or the care is not affordable.

This test is the crux of the adult dependent relative visa application. How you frame your case against this rule will define the path of the case. It’s important to choose your argument carefully.

Required level of care

The evidence you provide about long term care needs must also go on to explain what the applicant’s required level of care is. The Home Office provides helpful guidance:

The “required level of care” is a matter to be objectively assessed, with reference to the specific needs of the applicant. The level of long-term personal care must be what is required by the individual applicant to perform everyday tasks, in light of their physical needs and any emotional or psychological needs, in each case as established by evidence provided by a doctor or other health professional.

In considering whether the care is available in the country in which the applicant is living, the Entry Clearance Officer (ECO) will consider both what care is available, and whether it is realistically accessible to the applicant. As to the latter, consideration should be given both to the geographical location and the cost of such care.

Consider: what are the applicant’s actual daily needs? What care do they need to receive to meet those needs? To answer this, it can help to think about what an average day encompasses.

I’ve emphasised any emotional or psychological needs in the quote above because this is where we can really move one step beyond the physical tasks that a paid carer might fulfil. We can consider to what extent the applicant requires contact with the sponsoring family member just to get through their day. This guidance reflects paragraph 59 of Britcits v SSHD [2017] EWCA Civ 368 which clarified that ‘care’ could encompass emotional and psychological requirements, provided this was verified by expert medical evidence.

I’ve worked with several sponsors who have dedicated several hours per day to WhatsApp or Skype calls with their parent abroad. The calls were essential to keep mood up and stave off loneliness, sadness, and depression, but for many sponsors this kind of arrangement is unsustainable in the long term. In addition to direct calls, many sponsors spend time in their day co-ordinating aspects of their parent’s care with local neighbours, family or carers on a daily basis.

This intense time commitment is a real and important aspect of the required level of care. If we limit ourselves to proving only the physical components, it is very easy for the Home Office to dismiss those as mundane tasks that can be fulfilled by any able person paid to do them. The emotional components are much more interesting and must also be included in a rounded assessment of the required level of care.

Ideally, a medical professional or a psychologist or perhaps even a social worker will speak to the circumstances of the case. It is rarely going to be sufficient for a sponsor to just assert all of this. At least one expert really needs to link the narrative together with an objective and independent assessment and explanation of what the required level of care is.

No person in that country who can reasonably provide that care

After establishing the required level of care, the next question is whether there is any other person in that country who can reasonably provide the care. The key word is “reasonably”, and the concept of reasonableness can do a lot of heavy lifting here. There may well be people or institutions in the country that can provide care, but is that type of care reasonable?

The guidance explains what the entry clearance officer will be looking for when considering reasonableness:

The ECO should consider whether there is anyone in the country where the applicant is living who can reasonably provide the required level of care. This might be a close family member: son, daughter, brother, sister, parent, grandchild, grandparent, a wider family member, friend or neighbour, or another person who can reasonably provide the care required, for example a home-help, housekeeper, nurse, carer or care or nursing home.

If an applicant has more than one close family member in the country where they are living, those family members may be able to pool resources to provide the required care.

The concept of whether another person can “reasonably” provide care may require consideration of such matters as the location of that person, their own circumstances and other commitments, and their willingness to provide such care. The fact that a person or organisation has been providing care for a period may suggest that they can continue to do so, however, if evidence is provided as to the temporary nature of such care, or as to a change in circumstances, this must be carefully considered.

The provision of the care in the applicant’s home country must be reasonable both from the perspective of the provider of the care and the perspective of the applicant.

The question of reasonableness is where cases tend to diverge. Everyone has a different family set up. The onus is on the applicant to cogently explain and prove everything they assert. Are there relatives living in the same country who can’t help? Explain why and provide evidence. Is there a deceased partner/spouse? Prove it. Is there an excellent health care system that provides paid care which is nevertheless insufficient? Explain why and provide evidence.

This crucial part of the dependency rules is where you might be able to argue that the required level of care can only reasonably be met by the sponsor. You may for example be able to argue that whilst the applicant’s physical needs might be met by a carer, the applicant’s emotional support needs are such that a paid carer cannot fulfil the emotional role of a family member.

Continuing with the previous example of dementia or Alzheimer’s disease there is strong evidence available that sufferers can become upset or afraid of strangers, rendering “stranger care” unsuitable to meet their needs. There are many ways this can be argued, and ultimately you will need to produce evidence to back up all claims.

Framing the dependency argument

Consider these questions in order:

- What are the applicant’s long term personal care needs?

- What is the applicant’s required level of care?

- Is there a person in the applicant’s home country who can reasonably achieve the required level of care? For example, by reliance on local family or friends, paid domiciliary care, placement in a residential care home, or a combination of all of these? If not, why not? You will need to explain how the applicant has been getting by so far and why something different is required through a move to the UK. This is where you can often make a strong case to assert that the only type of suitable care is family care from a specific individual.

- If local free or paid care can meet the required level, then consider availability. Is care available? If not, why not? What steps have been taken to establish this? Can you provide evidence?

- If paid care is suitable and available, is it affordable? If not, provide costings and evidence.

If the circumstances allow you to focus and win your argument at point 3 above, you avoid getting into the weeds with 4 and 5.

Adult dependent relative visa applications very often get bogged down in debate about availability and affordability of care homes or paid carers in the country of origin. If you find yourself having these arguments with the Home Office, you have already conceded valuable ground and boxed yourself into a corner.

By engaging in debate about paid care, you are implicitly accepting the premise that paid care can solve the applicant’s care needs. The Home Office wants to have an argument about this, because most times the Home Office will win. You may eventually win such an argument, but the key to success is often establishing that no amount of care in the country of origin will ever meet the required level, and that the required level can only reasonably be met by the sponsoring family member.

If you can prove that even with the best medical and nursing facilities in the world, nobody but the sponsoring family member can reasonably care for the applicant, then you sidestep those tricky arguments about care availability and affordability.

Evidence, evidence, evidence

Like most immigration applications, the onus is on the applicant to prove their case. The decision-maker is not going to embark on their own evidence-gathering expedition. They will look at the documents you provide and make their decision.

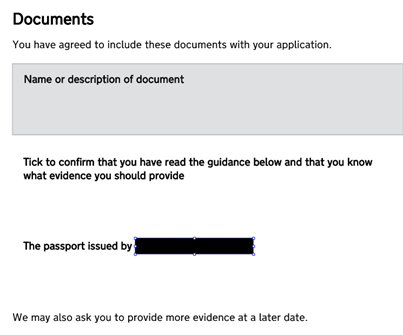

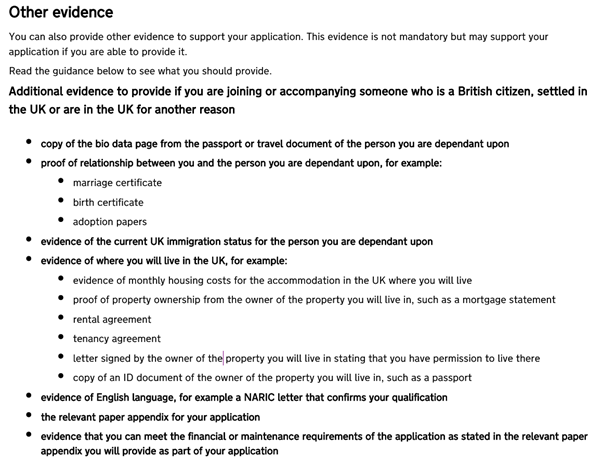

One problem with this is that the automatically generated document checklist issued by the Home Office does not provide any help at all. Here is a typical document checklist:

So that really isn’t much help at all, though it does hint at why the refusal rate might perhaps be as high as it is.

Proving long term care needs with independent medical evidence is absolutely essential. If you can’t or don’t provide medical evidence, the application will fall at the first hurdle. The Home Office guidance says you must provide:

Medical evidence that the applicant’s physical or mental condition means that they require long-term personal care because they cannot perform everyday tasks, for example washing, dressing and cooking. This must be from a doctor or other health professional.

Under paragraphs 36 to 39 of the Immigration Rules, the entry clearance officer has the power to refer the applicant for medical examination and to require that this be undertaken by a doctor or other health professional on a list approved by the British Embassy or High Commission.

If we skirt over the Alvi issue of a hard rule contained in guidance, it’s clear the Home Office quite reasonably wants to see independent medical evidence to explain the care needs. It’s not enough to self-assert the situation in a narrative on the application form or in a letter or statement. You absolutely must show something more, which crucially does not emanate directly from the applicant or the sponsor.

Strong medical evidence is the cornerstone of any adult dependent relative visa application. If you can obtain multiple medical reports from multiple medical professionals, even better. You may well need multiple reports if different health professionals are involved in different aspects of care. For example, an applicant may need reports from a general practitioner, a physiotherapist, a specialist consultant, a psychologist, a psychiatrist, or even a social worker.

Medical evidence should ideally set out, either in one report or in multiple reports:

- The author’s professional credentials and experience.

- The author’s knowledge of the applicant including details of any examinations that were conducted for the purposes of the report.

- All medical conditions that the applicant has been diagnosed with, and all treatment/medication they are currently receiving.

- The applicant’s current care needs, with a clear explanation of precisely what everyday tasks they require assistance with, and why.

- The prognosis: are the care needs just temporary with scope for full recovery, or are they long-term?

- What is the minimum level of care/support that the applicant requires? Where does this currently come from? If it is inadequate, why?

- Can the applicant’s care needs reasonably be met through paid domiciliary care? How about a care home? Explain.

- If arguing about care availability (or lack of), what is the care availability in the local area and the wider country?

This is absolutely not a finite list. Each case has its own unique facts and circumstances. Letters of instruction to medical professionals should be tailored to the case using your own judgement about what factors are important.

I often see unhelpful evidence: prints of hospital records, x-rays, scans, lists of medications and dosages, or a bare list diagnoses. Consider how a lay person seeing this evidence will react. Will they understand what you are showing them?

Unless the decision-maker has expert medical knowledge, they probably won’t be able to interpret the documents you are asking them to look at or draw meaningful conclusions to help your cause. These types of evidence can still be useful if combined with a report from a doctor contextualising them in plain English, but without context I never find these things helpful; I doubt the Home Office does either.

Don’t place unrealistic expectations on your decision-maker. Help them understand the case by providing useful and reliable evidence to guide them to their conclusion. If you don’t give them the courtesy of explaining what they are looking at, you can bet they are not going to embark on their own research to try and understand it.

If you feel you need more than a medical professional has been able to provide, consider whether you can add in objective evidence about a particular condition that an applicant suffers from. The NHS website can be a useful plain English resource with clear and coherent explanations of all sorts of medical conditions.

As a final thought on medical evidence, bear in mind that sponsors often have a much greater knowledge of their relative’s particular illness or disability; what seems obvious or self-evident to them might not be to you or to a civil servant. Don’t ever assume knowledge on the part of the decision-maker; the onus is on you to present a comprehensive case. Most cases I work on will still include a detailed statement from the sponsor, providing all of the context and background that cold medical evidence will likely lack.

Adequate maintenance and accommodation

The financial requirement is set out at ADR 6.1 – 6.5. The sponsor must be able to provide adequate maintenance, accommodation and care for the applicant in the UK without access to public funds. ADR 6.2 specifies the evidence required, depending on whether income or savings are being relied upon.

I won’t go into detail on this, but do not lose sight of the financial requirement amongst all of the dependency arguments. You wouldn’t want to succeed in a dependency argument and forget the financial evidence at the end.

Tuberculosis tests

Lastly, a reminder that applicants from countries specified in Appendix T: tuberculosis screening will be expected to produce a valid tuberculosis test from an approved clinic.

Article 8

If all fails, don’t forget article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights. ADR 7.1 – 7.2 specifically bakes article 8 into the rules. Before a decision-maker can refuse, they must consider whether the decision would result in unjustifiably harsh consequences for the applicant or their family. If you can’t quite squeeze a case under the dependency thresholds, perhaps there are other exceptional circumstances that can be brought in to make a compelling Article 8 argument.

Final thoughts

The purpose of this article is to emphasise that adult dependent relative visa applications can be successful. Approach initial applications as you would an appeal, because you may well end up in one. Lay the case out methodically, working through each element of the dependency test. Explain how you meet each limb. Prove everything you assert. Seek independent expert evidence where possible. Pay particular attention to whether you might be able to argue that only a family member can reasonably provide the required level of care.

SHARE