- BY Colin Yeo

*UPDATED* Tribunal rejects Home Office fraud allegation in ETS case but fails to report determination

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

The Qadir determination has now been reported: SM and Qadir v Secretary of State for the Home Department (ETS – Evidence – Burden of Proof) [2016] UKUT 229 (IAC). The headnote has been re-written, making this the third version of the determination to emerge into circulation. The new headnote reads:

(i) The Secretary of State’s generic evidence, combined with her evidence particular to these two appellants, sufficed to discharge the evidential burden of proving that their TOEIC certificates had been procured by dishonesty.

(ii) However, given the multiple frailties from which this generic evidence was considered to suffer and, in the light of the evidence adduced by the appellants, the Secretary of State failed to discharge the legal burden of proving dishonesty on their part.

The original headnote read:

The generic evidence upon which the Secretary of State has relied to date in all ETS cases has been held insufficient to discharge the legal burden of proof on the Secretary of State of proving that the TOEIC certificates were procured by dishonesty in circumstances where this evidence, via expert evidence and otherwise, has been demonstrated as suffering from multiple shortcomings and frailties and, further, the evidence of the two students concerned was found by the Tribunal to be plausible and truthful.

So why was it thought that there had been a deliberate decision not to report the case?

The first version of the determination appeared online on 11 April on Ben Amunwa’s excellent blog. I decided to wait for the official version before I wrote it up here on Free Movement. However, at a hearing on 15 April in open court an Upper Tribunal judge is reported to have stated that the Qadir case would not be reported.

UT reporting committee has apparently taken the decision not to report the ETS TOEIC test case decision. No idea why. #ukimmigration

— Rajiv Sharma (@Raj_Sharma_UK) April 15, 2016

Some members of the Bar got very excited at this point, and perhaps understandably so. It seemed extraordinary that such an important case would not be reported, if this were true. Some equally excitable solicitors even wrote a pre action letter to the reporting committee. A journalist following the story tried to find out more but got nowhere, eventually deciding to publish a piece on 21 April. An unreported version of the determination then appeared on the tribunal website and on BAILII the next day on 22 April. The published determination clearly stated that it was “Not reported”.

With a determination finally published which stated it was not reported, I finally wrote up the decision and I published the piece below on 25 April. Part of my piece addressed the apparent decision that the determination would not be reported.

It was all a mountain out of a molehill, it seems. It has emerged that the tribunal’s reporting committee did not consider whether to report the case until it met in May, the final determination in Qadir not having been ready in time for the April meeting. As soon as the reporting committee did meet, the case was reported.

President McCloskey has firmly rejected the Home Office case against students alleged to have fraudulently obtained English language test certificate from ETS (“Educational Testing Services Ltd”) in the case of SM and Ihsan Qadir v Secretary of State for the Home Department IA/31380/2014. The President finds that the Home Office evidence suffered from “multiple frailties and shortcomings” and that the two witnesses produced by the Home Office were unimpressive. In short, the Home Office failed by a significant margin to prove the alleged fraud.

The background to this case has been rehearsed before on this blog. Let us go through the Home Office’s own statistics, though:

| “More than…” | |

| Refusal, curtailment and removal decisions | 28,297 |

| Enforcement visits | 3,600 |

| Individuals detained | 1,400 |

| Individuals removed | 1,000 |

| Total removals and departures | 4,600 |

This is a very significant impact. Around 30,000 students have been affected, over 1,000 of whom were detained and removed. Case law states that the Home Office is permitted to remove such students from the UK before they had a chance to lodge an appeal. Given the stark findings against the Home Office in Qadir, it is difficult to see how any of these students could lose their subsequent appeals, unless the Home Office produces specific and further evidence. This calls into question the propriety of the Home Office decision to remove before the appeal can take place.

Much misery has been caused, a fortune in legal fees incurred and it is no exaggeration to say that the course of many people’s lives has been profoundly changed. There has also been media interest in the case and talk of a Parliamentary inquiry into the Home Office’s conduct in the case. This is what is generally known as public interest.

The conclusions in the case are general in nature and will be of interest to very many people, not least all those directly affected by the ETS affair. The headnote to the case makes the general nature of the conclusions very plain:

The generic evidence upon which the Secretary of State has relied to date in all ETS cases has been held insufficient to discharge the legal burden of proof on the Secretary of State of proving that the TOEIC certificates were procured by dishonesty in circumstances where this evidence, via expert evidence and otherwise, has been demonstrated as suffering from multiple shortcomings and frailties and, further, the evidence of the two students concerned was found by the Tribunal to be plausible and truthful

As well as these very important general conclusions on the evidence, the case also deals with some interesting legal and procedural issues. The Home Office is criticised for breach of its duty to adduce supporting documents, which is said by the President to be (para 15):

not harmonious with elementary good litigation practice and is in breach of every litigant’s duty of candour owed to the court or tribunal.

The President suggests that the Tanveer Ahmed case might not have application outside asylum and human rights cases (para 60). The President ruminates further on and develops his thinking on the “boomerang of proof” (para 57 to 60). The President describes as “inappropriate and misconceived“, and even improper, Mr Rory Dunlop’s suggestion for the Home Office that Judge Saini, who sits as a part time Deputy Judge of the Upper Tribunal, should not sit on the case because he might have acted as Counsel in some other ETS cases (Appendix 1, para 11-13).

At the end of the case, the President makes some important remarks of general importance not just to other ETS appeals but also to ETS judicial review applications and the increasing number of cases in which removal occurs before an appeal:

We are conscious that some future appeals may be of the “out of country” species. It is our understanding that neither the FtT nor this tribunal has experience of an out of country appeal of this kind, whether through the medium of video link or Skype or otherwise. The question of whether mechanisms of this kind are satisfactory and, in particular, the legal question of whether they provide an appellant with a fair hearing will depend upon the particular context and circumstances of the individual case. This, predictably, is an issue which may require future judicial determination.

This contrasts with the assumption by the Court of Appeal in Kiarie that the tribunal is expert in dealing with out of country appeals. The President’s admission is overdue and certainly reflects the position on the ground as argued in Kiarie [2015] EWCA Civ 1020. As a reminder, Richards LJ said this about out of country appeals in the immigration tribunal:

The Secretary of State is entitled, in my view, to rely on the specialist immigration judges within the tribunal system to ensure that an appellant is given effective access to the decision-making process and that the process is fair to the appellant, irrespective of whether the appeal is brought in country or out of country. They will be alert to the fact that out of country appeals are a new departure in deportation cases, and they will be aware of the particular seriousness of deportation for an appellant and his family. All this can be taken into account in the conduct of an appeal. If particular procedures are needed in order to enable an appellant to present his case properly or for his credibility to be properly assessed, there is sufficient flexibility within the system to ensure that those procedures are put in place. That applies most obviously to the provision of facilities for video conferencing or other forms of two-way electronic communication or, if truly necessary, the issue of a witness summons so as to put pressure on the Secretary of State to allow the appellant’s attendance to give oral evidence in person.

Given that the Immigration Bill will render all immigration appeals out of country ones, this issue is even more important than it might first appear.

The Qadir case also closes with some general commentary on the importance of maintaining an embargo on a draft judgment. Note here this paragraph is different in the officially unreported version as opposed to the unofficial unreported version:

Finally, we take the opportunity to emphasise strongly the caution and respect with which parties and representatives must treat embargoed judgments. All forms of unauthorised dissemination will be met with rigorous measures. Any slightest doubt should be proactively and timeously raised with the Tribunal.

Second, substantial excerpts from the embargoed draft judgment were disseminated, appearing on (inter alia) various websites. This occurred notwithstanding the unambiguous terms in which the embargoed draft judgment had been circulated to the parties’ representatives. An explanation of the parties’ representatives has been demanded.

The whole episode has, you will note, managed to give rise to two different versions of the determination in circulation [now three]. The Tribunal website version is always the official version to be used and relied on, but many lawyers prefer to use BAILII for ease of use and because it appears in native html web format.

Any of these legal issues would normally have been sufficient for President McCloskey to report this case, in my view. We have, after all, seen some inconsequential statements of the bleedin’ obvious given the imprimatur of a reported decision. This is a tendency previously highlighted on Free Movement, for example in Useful case (Pope is Catholic) [2014] UKUT 00000 and Discretionary and mandatory general grounds for refusal.

So, it is impossible to understand why the Reporting Committee has decided not to report the case of Qadir. The case is obviously of general and public interest. It has been given a headnote. The tribunal has even seen to it that the decision appears on the tribunal decisions page of its website, uniquely for 2016 among unreported decisions. Also uniquely amongst unreported decisions from 2016, it was quickly passed to the team at BAILII. It shows up in a BAILII search if you know what to look for but does not appear on the page of UTIAC decisions. At least one external observer in the media is baffled.

It has been published then, but not reported.

We do not know who is currently on the tribunal’s reporting committee, nor why some cases are reported and others are not and there are no minutes published. We do know that in 2014 only 15% of members of the committee were women, compared to 35% for the chamber as a whole. We know the published reporting criteria, which state:

The criteria for reporting cases include cases where the factual findings may be of some general interest.

We also know that the reporting committee has previously reported cases based on a factual dispute between parties in the context of allegations of fraud by students. See the case of NA and Others (Cambridge College of Learning) Pakistan [2009] UKAIT 00031, for example, where the outcome favoured the Home Office and the case was deemed suitable for reporting. We also know that the reporting committee from time to time makes its own non-judicial judgement as to what the law should be, as when it decided to report NA & Others (Tier 1 Post-Study Work-funds) [2009] UKAIT 00025 (reported on FM here) but not the ultimately correct allowed tribunal-level Pankina case (Pankina in the Court of Appeal and Supreme Court was on an appeal by the Secretary of State).

We also know that it is laborious to rely on an unreported determination. The immigration tribunal Practice Direction requires at paragraph 11 that a person seeking to rely on an unreported determination “certifies” various things first and applies for permission from the tribunal. Permission can be and is refused. How on earth a litigant in person is supposed to jump through this hoop is utterly beyond me. Why not just report the determination instead? For me this crystalises the issue, which is of transparency and of access to justice. The tribunal has erected many unnecessary hurdles to litigants in person and this is yet a further example.

Let us have a quick look at the practice direction:

11 Citation of unreported determinations

11.1 A determination of the Tribunal which has not been reported may not be cited in proceedings before the Tribunal unless:

(a) the person who is or was the appellant before the First-tier Tribunal, or a member of that person’s family, was a party to the proceedings in which the previous determination was issued; or

(b) the Tribunal gives permission.

11.2 An application for permission to cite a determination which has not been reported must:

(a) include a full transcript of the determination;

(b) identify the proposition for which the determination is to be cited; and

(c) certify that the proposition is not to be found in any reported determination of the Tribunal, the IAT or the AIT and had not been superseded by the decision of a higher authority.

11.3 Permission under paragraph 11.1 will be given only where the Tribunal considers that it would be materially assisted by citation of the determination, as distinct from the adoption in argument of the reasoning to be found in the determination. Such instances are likely to be rare; in particular, in the case of determinations which were unreportable (see Practice Statement 11 (reporting of determinations)). It should be emphasised that the Tribunal will not exclude good arguments from consideration but it will be rare for such an argument to be capable of being made only by reference to an unreported determination.

11.4 The provisions of paragraph 11.1 to 11.3 apply to unreported and unreportable determinations of the AIT, the IAT and adjudicators, as those provisions apply respectively to unreported and unreportable determinations of the Tribunal.

11.5 A party citing a determination of the IAT bearing a neutral citation number prior to [2003] (including all series of “bracket numbers”) must be in a position to certify that the matter or proposition for which the determination is cited has not been the subject of more recent, reported, determinations of the IAT, the AIT or the Tribunal.

11.6 In this Practice Direction and Practice Direction 12, “determination” includes any decision of the AIT or the Tribunal.

The reporting committee may think the Qadir case merely involves a factual dispute between parties and is therefore not suitable for reporting. They are wrong:

- Firstly, the fact it involves a factual dispute between parties is not a barrier to it being a reported case, as is made plain by the reporting criteria and past decisions of the reporting committee. There are countless other determinations which amount to factual disputes between the parties. The Cambridge College of Learning case is one obvious example that springs to mind (which the Home Office won and which was reported), but there are also countless asylum cases, country guidance or otherwise, which are reported.

- Secondly, the case does deal with legal issues. The reporting committee may think these legal issues unimportant or underdeveloped, but that has not stopped many an inconsequential case being reported. The President has even reported cases where one of the parties was not even represented, for goodness sake, and there was literally zero legal argument from one of the affected parties.

- Thirdly, what is sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander. If the Home Office had won in Qadir and had shown that there was widespread fraud that was provable with generic language analysis evidence, would the case then have been reported? For my part, I consider the answer to that question to be an unequivocal “yes”. The Cambridge College of Learning case was certainly reported.

Mayfair Solicitors have sent a pre-action letter to the chair of the reporting committee. You can read it here. It could perhaps have done with a little editing and arguably it might have been wise to include an actual response date, as is required by the pre action protocol. Events have moved on since that letter, though, as the determination is at least now publicly available even if the artificial barrier of it being unreported has been erected.

So why is the case not reported? Leaving it unreported can only help the Home Office in future individual ETS appeals. And this is not the first time that the tribunal has allowed itself to be seen as favouring one party over another. In judicial review claims, for example, Home Office failure to serve documents is met with automatic extension of time with no costs penalty. Claimants who fail to serve forms on the Home Office are met by automatic strike out of their claim. Costs are enforced against claimants for poor litigation conduct but not the Home Office. Worryingly, inadequately reasoned “totally without merit” certificates appear to have been used to manage workload by eliminating as many as 50% of claimant cases in order to meet performance expectations set by the Government.

From this we can take that some judges of the Upper Tribunal consider that Government interests are too important to be sacrificed on the altar of procedural failure, unlike the interests of claimants. Claimants should not be permitted victory just because the Home Office is so badly organised, unlike the Home Office against claimants. Those judges fail to realise that quashing a Home Office decision and awarding costs to the claimant would not lead to actually lead to a substantive victory, necessarily, not unless a rare mandatory order were also made.

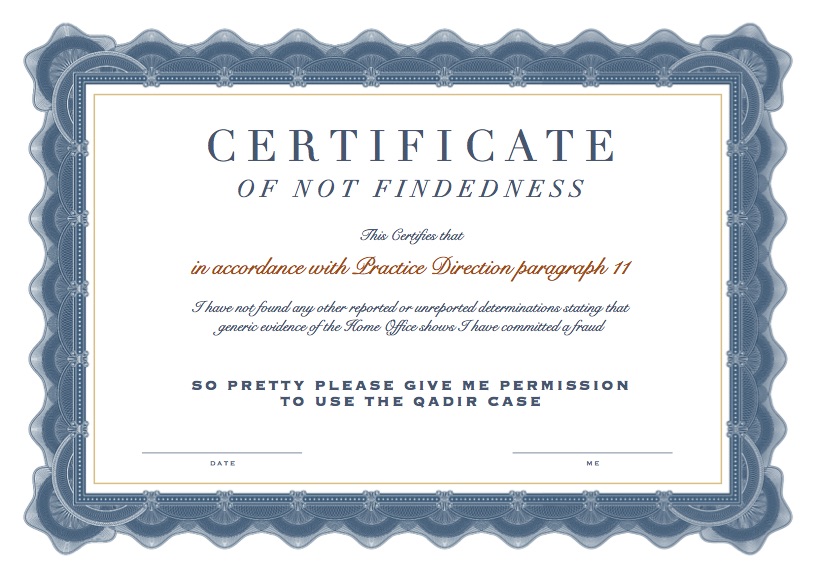

As a free bonus resource for Free Movement readers, I offer you a mock certificate for use in court, complete with the frilly bits that the officious Practice Direction seems to demand.

Nevertheless, even with this marvellous certificate, we can expect some judges to refuse to admit Qadir into proceedings. The refusal to report the decision allows and even encourages First-tier judges to disregard Qadir, which can only benefit the Home Office and ramp up the legal costs for claimants. Should any judge refuse to admit Qadir in a case in which it was relevant this would no doubt be an error of law; which surely highlights the laughable absurdity of failing to report the decision in the first place.

Source: Qadir (IA313802014 & IA363192014) [2016] UKAITUR IA313802014 (21 April 2016)

SHARE

4 responses

I might just be tempted to use that certificate at the end. A judge, who I like very much, has already had the opportunity to exclude Qadir in a case brought before him. No doubt he was correctly relying on the practice direction to exclude the decision as I would imagine most practitioners are unfamiliar with the laborious process of seeking permission to rely on an unreported case.

The advantage of it not being reported is that you can still argue that the Secretary of State has not discharged the burden of proof, not even ‘ narrowly’ , and that the Secretary of State’s statements are all just a lot of hot air and no substance.

The rumor mill says that the case is being appealed by the Home Office in the hope that they can get a better judgement from the court of appeal. The Home Office seek to argue, among other complaints, procedural unfairness, in that Judge Saini did not recuse herself. So the circus rolls on and no doubt the next show in the next town will feature much of the same. I wonder if the Secretary of State will ask any of their Lordships to step aside?

Justice awaits just around the next blind bend. Unfortunately the toll booths are being assembled behind the caravan.

Justice may eventually be found somewhere along the road, but by then few will be able to afford the ticket.

https://freemovement.org.uk/massive-increase-in-immigration-appeal-fees-proposed/

Thanks, Julian. Are you saying that a judge refused to look at Qadir because it was not reported?

Yes that’s what I understand happened. It was after the reporting committee decided not to report the case and the SIJ gave the barrister a bit of a roasting for not complying with the practice direction

Does El Presidente sit on many cases that are deemed unworthy of being reported, I wonder?