- BY Daniel Rourke

How to extend ‘Calais’ leave and leave under section 67 of the Immigration Act 2016

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Table of Contents

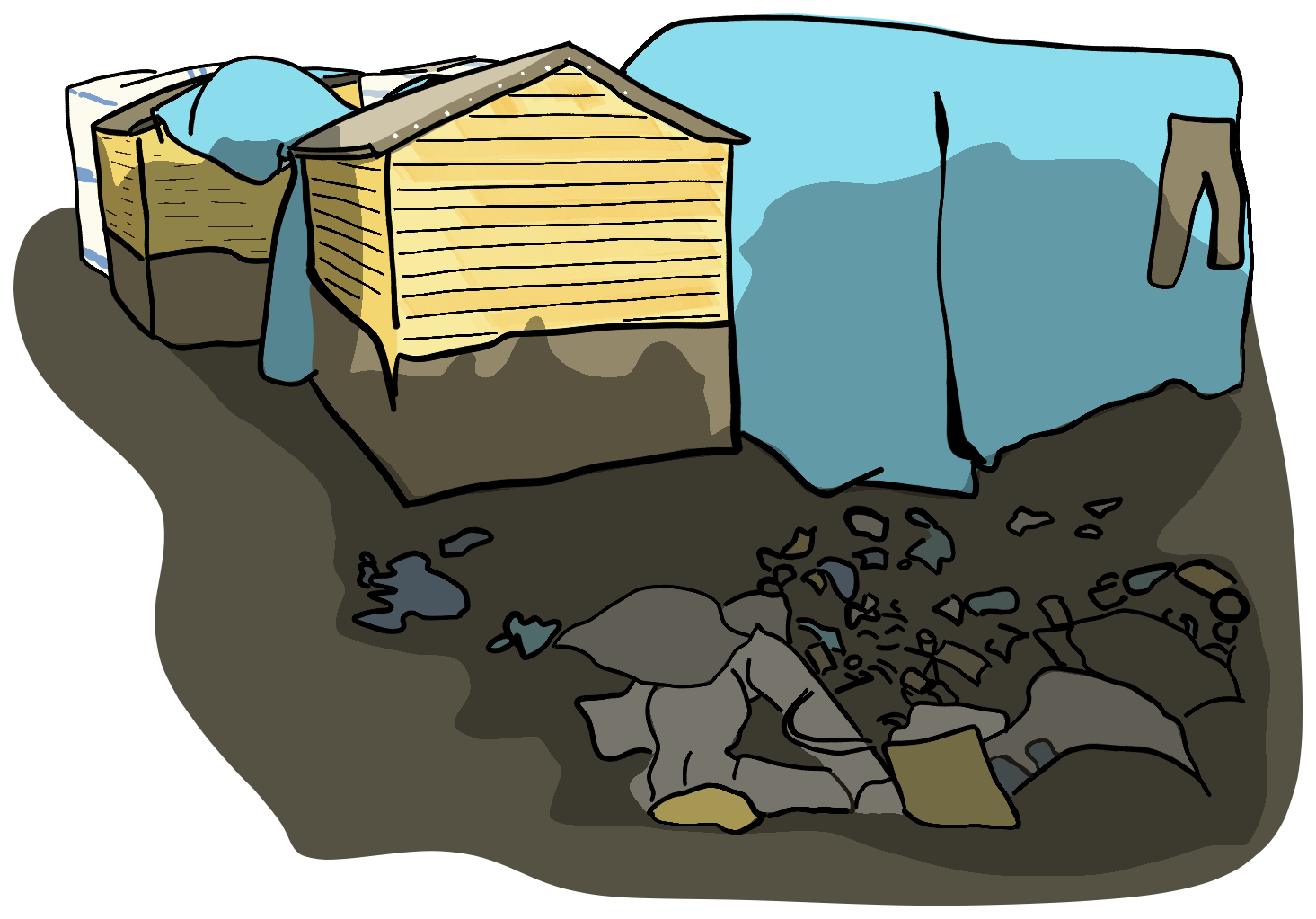

ToggleIn recent months two cohorts of young people, those granted ‘Calais leave’ and those granted leave under section 67 of the Immigration Act 2016, have begun to reach the end of five years’ limited leave to remain. The immigration rules currently provide a route to either further limited leave or indefinite leave to remain for each cohort.

Previously those with ‘Calais leave’ had to wait ten years before being able to settle but the Home Office has recently announced that they will be granted indefinite leave to remain after five years. However, the Home Office has to date failed to publish any guidance on the practicalities of making applications for either of these groups and there are no specified application forms.

Background

Both cohorts were invited to travel to the UK by the Home Office as unaccompanied asylum-seeking children following widespread public concern in 2016. Two bespoke forms of leave were eventually created and granted from 2018. Both forms of leave follow an unsuccessful asylum application. Each were expressly intended to lead to settlement in the UK without payment of the normal fees.

‘Calais leave’ was granted to individuals ‘identified for transfer to the UK as unaccompanied children in connection with the clearance of the Calais camp, to reunite with qualifying family’. Calais leave was granted initially for five years, to be followed by a further five years if conditions are still met. An application for indefinite leave can be made after 10 years.

Section 67 of the Immigration Act 2016 began life as an amendment to that Act moved by Lord Alf Dubs. Lord Dubs is a Labour peer who fled the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia as a child on the Kindertransport.

Section 67 required the Home Secretary to relocate unaccompanied asylum-seeking children to the United Kingdom from other European countries. A specified number (480) was set following consultation with local authorities. ‘Section 67 of the Immigration Act 2016 leave‘ (‘s. 67 leave’) as it is referred to was also initially granted for five years. However, an application for indefinite leave can be made after the initial five years.

Therefore, until now the position has been that people with s. 67 leave could apply for indefinite leave five years sooner than people with Calais leave. That is the same amount of time recognised refugees must wait before applying for indefinite leave.

The disparity between these two routes is set to change as the Home Office has now indicated its plans for young people with Calais leave. They will soon also be able to apply for indefinite leave after the initial five years.

However, the Home Office has not confirmed how it will treat those individuals who have already overstayed their leave. It also remains unclear how applicants with s. 67 leave can apply for indefinite leave.

Where leave is about to expire, individuals should protect their position before their current leave expires by making an in time application to extend their leave. Doing so extends their current leave pending the outcome of the application under s. 3C Immigration Act 1971.

Calais leave – the current position and making an application

The immigration rules simply state that, “at the end of the five-year period, if each of the [original requirements for Calais leave] continue to be met, the person will be granted Calais leave for a further period of five years”.

To be valid, any application for leave to remain must generally be made on the specified form (paragraph 34, immigration rules). However, there is no such form for an application to extend leave in this route and the Calais leave policy (version 3.0, published 31 December 2020) is silent on how to extend leave after five years.

There is however guidance for applicants who apply outside the rules (where there is necessarily no specified form). That states to use the form which ‘most closely matches their circumstances’ (page 9), paying any relevant fees and charges.

The guidance for form FLR(HRO) states ‘Use this form to apply online to extend your stay in the UK for human rights claims, leave outside the rules and other routes not covered by other forms.’ However, submission of that form requires payment of a £1,048 fee and the immigration healthcare surcharge. In this case, the surcharge would be £1,035 per year for five years (£5,175).

The combined fee is likely to be prohibitive for most young people with Calais leave. It should also be noted that the published policy on Calais leave indicates that the immigration health surcharge does not apply (page 10). In such cases, an application for a fee waiver can be submitted. That action will serve to activate s. 3C leave (see further on how to apply for fee waivers).

Calais leave – anticipated changes

The Home Office told Children’s ‘Stakeholder Engagement Group’ on 27 March that:

The Home Secretary has agreed that the Calais leave cohort’s route to settlement will change to a 5-year route instead of the current 10-year route. This means that all of those who met the requirements for an extension of Calais leave at the end of the initial 5-year period will instead be granted settlement, subject of course to the outcome of criminality and suitability checks.

The Home Office is aware that whilst Calais leave has expired for the majority of its cohort, most individuals have made in-time applications for further leave to remain and so their permission has been extended by section 3C of the Immigration Act 1971. We have worked with operational colleagues to briefly pause consideration of these applications whilst we operationalise the changes below. This will be communicated to relevant applicants imminently.

We are currently in the process of updating policy guidance to reflect the latest policy position, which will be published as soon as possible. Grants of settlement for this cohort will be outside the Immigration Rules. Consideration will be given as to whether to amend the Immigration Rules to reflect this change, or remove altogether, in slower time – our current and immediate priority is granting this cohort settlement without further delay. No fee will be payable for this consideration and anyone with an outstanding application for leave to remain that has paid a fee and is subsequently granted settlement in-line with the updated policy will be identified by the Home Office and their original application fee will be refunded. Furthermore, any individuals within this cohort who are granted settlement in-line with the updated policy and have paid the Immigration Health Surcharge as part of their application for further leave to remain will also have this refunded.

We will shortly contact all individuals who have been granted Calais leave to explain their new path to settlement. Alongside this letter will be a proforma which we request be filled out by the applicant to gather information to consider the individual’s suitability for settlement.

Calais leave – What if no in-time application was made?

The position is less clear for those young people whose leave lapsed without an in-time application being made. What is clear is that they do not currently have leave. They are subject to the consequences that stem from the hostile environment – inability to work, rent, etc.

These individuals will be contacted by the Home Office in the same way as those who have lodged in time applications. Depending on their circumstances, they may not wish to take action in advance of being contacted but it is likely to be in their best interests to try to progress their case as quickly as possible.

This could take the form of a pre-action letter for judicial review, providing all information considered relevant to settlement, highlighting any problems the client is experiencing and requesting a prompt grant of indefinite leave. Judicial review proceedings accompanied by an application for interim relief could then be considered. During the period they do not have leave they should take care not to commit offences by, i.e. illegal working.

Section 67 leave – the current position and making an application

As with Calais leave, there is no specified form. Again, the published policy is silent. The decision to be made is what form most closely matches the applicant’s circumstances.

Applicants could use the FLR(HRO) form, given its description as a catch all that can be used for ‘other routes not covered by other forms’. However, it carries with it the £1,048 fee and is orientated toward applications for limited leave to remain. Whereas a written ministerial statement (Caroline Nokes, 15 June 2018) indicates that applications for indefinite leave on this route should be fee free and this is reflected in the fee regulations.

We consider that applicants approaching the end of their five-year initial grant of leave to remain should instead apply using the form provided to refugees (SET(P)). It should be made clear repeatedly on the application that the applicant holds s. 67 leave not refugee status (Ed: guidance has now been published saying that SET(P) is the correct form).

Anecdotally, we understand that caseworkers in the Home Office have indicated to MP’s offices that this will be accepted. However, we recommend its use on a principled rather than anecdotal basis. It is the form that most closely matches the applicants’ circumstances. It applies to people who were granted leave following an application for protection. They are applying for indefinite leave after five years limited leave. It is the only relevant form that is fee free and it is clear no fee should apply.

Conclusion

Amidst its other ‘priorities’, the Home Office overlooked the long-term commitment it made to these two cohorts of young people. Following efforts by stakeholders, as well as pre-action correspondence by a Lawstop client and others, the Home Office is poised to update its policy. The change should benefit those with Calais leave by shortening their route to settlement by five years.

Individuals with Calais leave should soon be able to apply for indefinite leave. They should be contacted directly with a form allowing them to do this. If they have paid fees these should be refunded. Individuals whose Calais leave is expiring imminently and who have not yet received the new form should apply on Form FLR(HRO) or for a fee waiver to protect their leave in the meantime.

Where individuals have overstayed their leave, they should contact the Home Office asking for an urgent grant of indefinite leave to remain under this new policy. Where the Home Office declines to do so, judicial review should be considered.

Individuals with s. 67 leave should apply on SET(P), the form used by refugees.

Hopefully efforts to clarify the guidance applicable to these two cohorts will mean a definitive answer soon.

This article was first published on 4 April 2024 and will be updated in light of any developments.

This post was co-written by Elliot Chappell, a trainee solicitor in the Strategic Litigation Team at Lawstop, a legal aid firm with initiatives in Housing, Community care, Public Law, Education and Immigration.