- BY Esme Madill

Albanian asylum claims: making a difference

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

All asylum seekers, including children and young people, find that the starting point for any official making a decision in their case is to doubt their narratives and subject them to disbelief and incredulity. Even in this climate of disbelief, Albanian asylum claims have been singled out for particular hostility.

Breaking the Chains — a partnership project between the Migrant and Refugee Children’s Legal Unit (MiCLU) at Islington Law Centre and Shpresa Programme — is dedicated to improving outcomes for Albanian children and young people seeking asylum. It has just launched an interim evaluation report presenting key findings from Year 1 of the project.

This article gives an overview of the problem, the project and the findings of the evaluation.

Few Albanians get asylum

Albania has been described as Europe’s first narco-state. The country has a long history of clan violence, blood feuds and revenge killings, as well as political instability. Domestic abuse, so-called ‘honour-based’ violence, gender-based violence and child-specific persecution appear in many Albanian asylum claims. Albania is also a source country for one of the largest groups of trafficked women and children to reach the UK’s shores. Unaccompanied asylum-seeking children from Albania, who have been trafficked or who are fleeing violence, arrive in the UK each year, destitute, exhausted and traumatised.

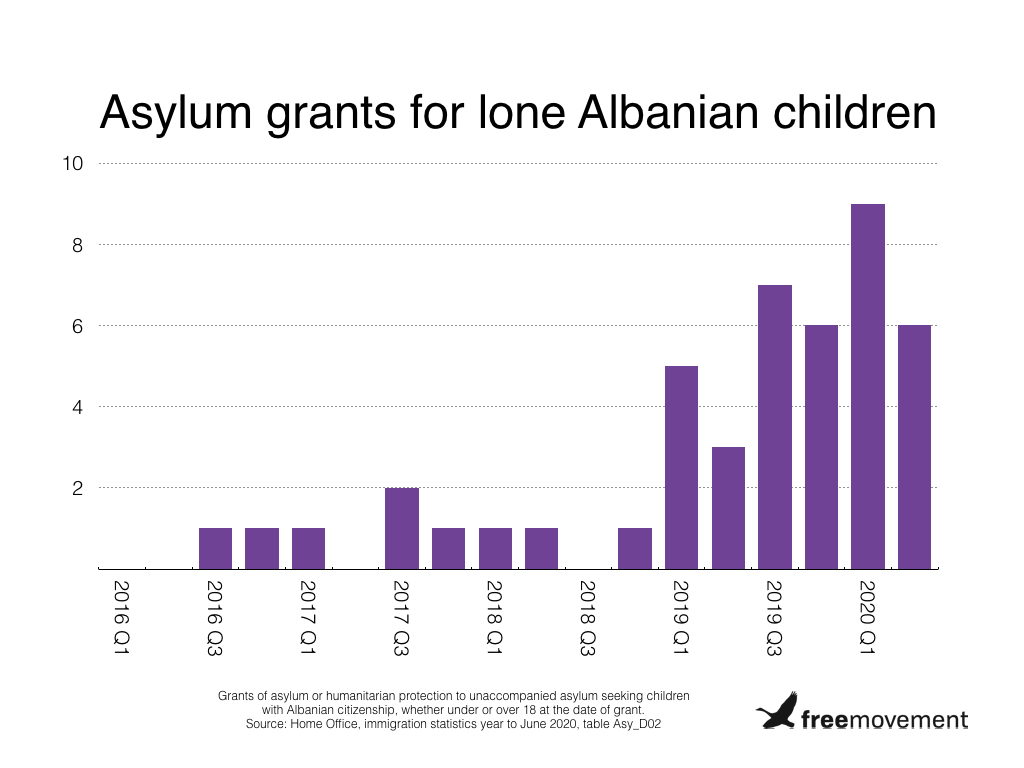

The government’s approach to their asylum claims does not accord with the reality on the ground. In recent years, grants of asylum to Albanian unaccompanied minors have been in single figures.

Poor quality legal advice

The legal aid system acts as a disincentive for immigration lawyers to take on cases which are certain to be time- and resource-intensive. The result is that many Albanian children and young people are represented poorly and a vicious circle emerges: immigration judges repeatedly presented with poorly prepared Albanian claims find it hard to avoid assuming these claims have little merit.

As Ronan Toal of Garden Court Chambers says, these young people:

have got a massively uphill struggle, in the first place because of the culture of disbelief, and because of the country information… the understanding of Albania that is shared by the Home Office and tribunal. In trying to make good their asylum claims they are further impeded by really poor quality legal representation. Often these solicitors will ditch the clients after a bad decision — for example a decision to certify an asylum claim as clearly unfounded, or to dismiss an appeal — leaving them completely in the dark. They frequently end up as refused asylum seekers with no lawful basis for being here, in the increasingly hostile environment, and even more vulnerable to exploitation and abuse than they were before.

Children and young people who are already vulnerable find themselves denied access to work and education, frequently lack support, and rarely have access to high-quality legal advice. One says:

I feel like I am being forced to beg the Home Office for the right to be safe. Mostly now I think I should just go back and be killed. At least there would be some dignity in that. In Albania, I was working from the age of 10 or 11. Here I can do nothing. Just hang around and have people tell me I must be some drug dealer or gangster because I am Albanian. But I am just a human being. I have feelings like everyone else.

Those working on the ground with Albanian teenagers across London testify to increasing rates of self-harm and suicide attempts as children and young people, already subject to past trauma, lose faith in the justice system and struggle to cope with both the pervasive assumption that they are liars and the near-certain refusal of their asylum application. When refused asylum (after many years) they frequently disappear into a half-life on the margins, invisible, pushed into modern slavery, facing situations as precarious as those they have fled.

Breaking the Chains

Breaking the Chains was founded by Shpresa Programme and MiCLU in 2018 in response to consultation with Albanian children and young people. Funded by the Paul Hamlyn Foundation, the project is designed to meet the specific needs of Albanian asylum-seeking children and young people by providing a holistic legal representation and advice service, which is child-centred and child-friendly.

The project recently launched an interim evaluation report by Dr Rachel Alsop from the University of York. The report details key findings from Year 1 of the project. Dr Alsop wrote that:

…the lived experiences of the young people, their concerns and their ideas, shape practice every step of the way. During the legal training-sessions, the lawyers listen to the feedback from the young people and adapt their own delivery of training accordingly, to maximise its accessibility and reach.

This model of child-centred practice contrasts with the experiences of the young people elsewhere in the legal system. They recount numerous experiences of legal representatives who have not listened to them or given them the time and space to build up the trust to share their stories; of being fobbed off with shoddy legal practice; of daunting and bewildering encounters with Home Office representatives; or of intimidating court hearings where judges have been dismissive and curt.

Key to the success of the project, Dr Alsop found, is the value and respect it accords its young clients. Shpresa Programme, an award-winning, user-led refugee community group, provides intensive support to children and young people, founded on a belief in the potential of each individual. Caseworkers at Breaking the Chains confirm that they are only able to engage with and support the vulnerable young people on their caseload with the dedication of the skilled and experienced Shpresa staff who triage day and night when young people are overcome with despair and struggle to find a reason not to give up.

Dr Alsop also found that partnership with Garden Court Chambers was essential to the project’s success, helping to change the narrative that Albanian claims are unwinnable. A team of barristers supported the project from the outset, offering advice and representation in complex cases. David Neale, legal researcher at Garden Court, has developed a suite of resources to guide those representing children and young people from Albania. With Gurpinder Kaur Khanba, the Breaking the Chains casework supervisor at MiCLU, guidance has been made available for solicitors and caseworkers on how to prepare Albanian asylum claims. This includes information on approaching the Legal Aid Agency and obtaining funding for expert reports at the pre-decision stage.

More quality representation needed

As Anna Skehan, Legal Practice Lead at MiCLU, told the evaluation:

There are so many children and young people who are engaged in Shpresa who are receiving inadequate or no legal advice. However many we take on…there immediately are more that need representation just as desperately.

With the help of Garden Court, Breaking the Chains has shown that with expert, tailored legal advice, Albanian cases can succeed. For Albanian young people in the asylum system this is not just life-changing but life-saving. As one young Albanian said:

Without Shpresa and MiCLU my life would be completely different. They [have] given to me a lot. They gave me my life back. They have given me the chance to have a bright future so I can become a ‘little helper’ for this country because I can work and can pay my own bills, same as everyone does. Everyone came here for a safe life and now that I have my leave to remain, my feeling [is that I ] will live and I will not need to think about death.

Find out more

If you would like to help improve outcomes for vulnerable young asylum seekers and have the capacity to take on cases, please visit the Breaking the Chains website to register your support.

To read more about the project, including the interim evaluation report, please click here: https://miclu.org/btcy1. You can also sign up for upcoming legal seminars:

23 October 2020: The CPIN and assessing merits in Albanian claims, David Neale

20 November 2020: Expert evidence, Gurpinder Kaur Khanba

11 December 2020: Working with your young client, Kathryn Cronin

22 January 2021: Albanian culture and heritage, Gurpinder Kaur Khanba, Esme Madill and Shpresa’s Immigration Champions

This article was co-authored with Dr Rachel Alsop.